Learning any subject or skill can be a long, difficult and full of obstacles. Whether acquiring a university degree, speaking a new language or knowing how to cook, all of them are learning that involve many steps, all of them essential.

It usually happens that as we become more skilled in certain knowledge and skills we “forget” how much it cost us to learn, thinking that novices in this knowledge can skip some steps that we do not realize are fundamental for their learning.

This whole idea comes to be what is known as the expert’s blind spot, a cognitive bias that occurs in those people who have managed to acquire extensive knowledge in a certain knowledge. Let’s look at it further.

What is the expert’s blind spot?

Let’s think about the following situation: we are walking down the street and a man stops us, who turns out to be an exchange student from the United States. The boy asks us to teach him to speak Spanish, to which we answer yes. We become friends with him and specify a few days in the week to give him “classes.” After several weeks of trying to teach him things we see that he has only learned the most basic phrases and the occasional word and that is when we ask ourselves, where have we gone wrong?

We review our “lessons”. We start with something soft, the basic phrases and vocabulary that he has learned, but then we see that we have jumped to the verb tenses, thinking that the American kid would grasp them the first time. We have thought that its acquisition could be done by the natural method, simply “capturing” in which situations it is appropriate to use one verbal form or another. We insist on it and we see that we are stuck, that he does not learn more.

One of the most common problems when learning languages (and any other subject) is trusting that native speakers of the target language are experts at teaching their own language We can really assure that Spanish speakers are experts at speaking it: they know when to use verb tenses, the appropriate vocabulary for each register and situation, maintain a fluid conversation rich in themes… but what not everyone knows is how to teach their own language, since they lack the pedagogical tools to teach it to a native speaker of another language.

This entire hypothetical situation describes an example of what would be the expert’s blind spot, which is the cognitive bias that occurs when a person who has extensive knowledge of a certain subject or skill has lost track of how difficult it was for them to acquire that skill In this case, the person who has tried to teach Spanish to the American has ignored that she learned his native language after many years of being immersed in it, hearing it at home and studying it more thoroughly at school. Unlike a Spanish teacher, the native speaker, even if he knows how to speak, does not know how to teach.

The expert model

It is obvious that you cannot teach what you do not know, that is, what you do not have deep knowledge of. However, and as we introduced with the previous example, the fact of having extensive mastery in a certain topic or skill is not a guarantee that we will be able to teach it properly, in fact, it is even possible that it makes the task of teaching difficult for us if We don’t know exactly how to do it.

The idea of the expert’s blind spot, which, as we have mentioned, is the situation in which a person knows a lot but does not know how to teach it, is an idea that at first may seem counterintuitive but, both taking the previous example and things that happen to us in our daily lives, it is quite likely that more than one person will identify with this situation. Surely it has happened to us on more than one occasion that we have been asked how to make a dish, get to a place sooner or practice a sport that we are very good at and we have not been able to explain it well. It is a very common situation.

Our knowledge influences the way we perceive and interpret our environment, determining the way we reason, imagine, learn and remember. Having an extensive substrate of knowledge on a certain topic gives us an advantage, in that we know more, but at the same time it makes our mind feel a little more “scrambled”, with a tangle of threads that represent the different knowledge that we have internalized. but we do not know how to unravel it in a pedagogical way for a person who wants to learn.

To understand the phenomenon of the expert’s blind spot We must first understand how the process that goes from the utmost ignorance to expertise in a certain knowledge occurs, having the model proposed by Jo Sprague, Douglas Stuart and David Bodary. In their model of expertise, they explain that to achieve broad mastery of something, it is necessary to go through 4 phases, which are distinguished based on the acquired competence and the degree of awareness of the assimilated knowledge.

1. Unconscious incompetence

The first phase of the model is the one that occurs when a person barely knows anything about the discipline or skill they have just begun to learn, finding themselves in a situation of unconscious incompetence. The person knows very little, so little that he is not even aware of all that he still has to acquire and how little he really knows. She does not have enough knowledge to determine his interest in the knowledge he is acquiring nor to appreciate the importance it may have for him in the long term.

Your ignorance can lead you to be a victim of a curious psychological phenomenon: the Dunning-Kruger effect. This particular cognitive bias occurs when the person, even having very little knowledge, believes themselves to be an expert, ignoring everything they do not know and even believing in the ability to discuss at the level of an expert in the subject. It is what in Spain is colloquially called “brotherhood”, that is, showing an attitude of someone who appears to know everything, being sure of it, but who in reality knows nothing.

Everyone is a victim of the Dunning-Kruger effect at some point in their lives especially when they have just started some type of course and they get the feeling that what they are being taught is very easy, underestimating the real difficulty of learning.

2. Conscious incompetence

As you progress in learning, you realize that you really don’t know much and that we still have a lot to learn. This is when we enter a moment in which we are aware of our incompetence on this issue, that is, we realize that we are still quite ignorant. We have realized that what we have set out to learn is actually more complex and extensive than we initially believed

At this point we begin to estimate our options to master the subject and how much effort we will need to invest. We begin to consider the value of that specific knowledge, how long the road is and whether it is worth it to continue moving forward. This evaluation of our own ability to continue progress and the importance we attribute to the acquisition of that knowledge are the two most important factors that determine the motivation to continue learning.

3. Conscious competition

If we decide to continue being in the second phase, sooner or later we enter the third, which is reached after significant effort and dedication. In this phase we have consciously become competent, a situation in which we know how much we have learned, although we may be a little slow in explaining it or very careful when testing our skills, being afraid of making mistakes.

4. Unconscious competition

The fourth and final phase of the expertise model is the one in which we have unconsciously become competent. What does this mean? It means that we have become experts in a certain skill or discipline, being very fluid and efficient when it comes to putting our knowledge into practice. The problem is that we are so competent that we are losing our ability to “explain” everything we do. It is not so natural that we skip steps that we consider unnecessary, we do things more quickly, we act as if by inertia…

The expert has so much knowledge that he can perceive things that people who are not experts in that matter do not appreciate, and You can reflect in a much more critical and profound way about different knowledge that is related to what you have learned You can easily see relationships between different aspects of what you are an expert in, since having a broad domain can find their similarities and differences more automatically. Your perception, imagination, reasoning and memory operate in a different way

Ironically, in this phase the exact opposite effect of the Dunning-Kruger effect occurs: imposter syndrome. The person knows a lot, so much that, as we said, he thinks automatically and by inertia and, because of this, he is not aware of how much he really knows. Despite being an expert, he feels insecure in situations where his knowledge is required.

What does all this have to do with the expert’s blind spot?

Well the truth is that a lot. As we have seen, as we become experts in a certain subject there is a moment in which our knowledge and skills become something very internalized, so much so that we are not even aware of all the processes and actions we carry out related to them. The more practice and knowledge, the easier it is for us to do things. Something that used to take us a long time to do now only takes a few minutes

Let’s go back to the example from the beginning. Are all of us Spanish speakers constantly thinking about how we should structure sentences grammatically correctly? Are we aware of how we should pronounce each phoneme of each word? When we say “house,” do we literally mean “house”? Perhaps a small child will be careful not to get sentences wrong or make mistakes in sounds, but of course a native adult will speak much more naturally and fluently.

As adults we skip all those steps since we rarely make a mistake in pronunciation or make a grammatically strange sentence. We have internalized speech. However, we must understand that at some point in our language learning we had to go through these processes since if we had not been aware we would never have internalized them or learned to speak properly. The problem is that we do not take this into account as adults and, although with good intentions, when it comes to teaching the language to a foreigner we do not know how to do it.

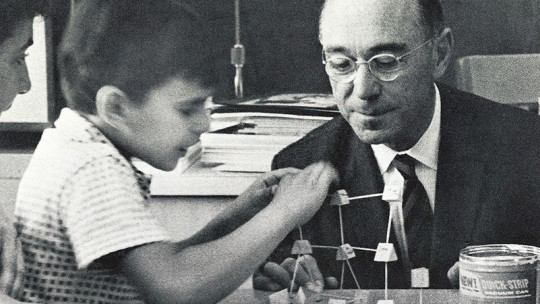

All this It allows us to reflect on how important it is for anyone who wants to teach something not only to know that something, but also to know how to teach it For example, language teachers must not only know how to speak the language they teach, but they must also know how to teach it to specific foreign language speakers, the age and level of the speaker in question, and whether they have any difficulties in pronunciation. associated with their native language.

This, naturally, can be extrapolated to other subjects. One of the things that has been criticized in teaching is that many teachers who are experts in their subjects such as mathematics, social sciences, natural sciences… overestimate their students’ ability to learn the syllabus. These teachers have so internalized the knowledge they teach that they do not give due importance to some steps, thinking that the students already know it or will understand it quickly. It may happen that you see your students as “little experts” and the teacher ends up omitting steps that, in reality, are crucial.

Taking all this into account It is essential that when designing the educational curriculum, the real learning rate of the students is taken into account, not assuming anything and making sure that teachers, in addition to being experts in the content they teach, are also experts in sharing it. The blind spot bias of the expert is like a curse of the one who knows a lot, that he knows so much that he does not know how to explain it, and a good teacher is, above all, someone who knows how to share his knowledge.