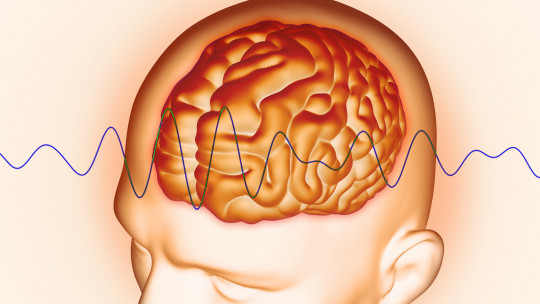

Sleep is defined as a naturally recurring state characterized by altered consciousness, relatively decreased sensory activity, reduced interaction with the environment, and inhibition of the activity of almost all voluntary muscles (during REM).

Sleep is considered an essential activity for all animals, since it is established at an evolutionary level in any complex taxon. When we rest, we find ourselves in an intermediate situation between wakefulness and total loss of consciousness.

It is estimated that brain activity during a coma is 40% compared to the basal state of wakefulness, while in the deepest moment of sleep a brain activity of 60% is still maintained.

On the other hand, in the REM phase of sleep (established an hour and a half after starting to sleep), brain activity is very similar to that present in a completely awake state.

We can take for granted the physiological realities that happen in our body, but the reality is that not even we know why many of the processes that define us as a species take place, no matter how accustomed we are to carrying them out. If you want to know why we sleep, keep reading

Circadian rhythms and the biological clock

Understanding why we sleep is not entirely easy, but the mechanism that causes this situation has been described on multiple occasions. First of all, it should be noted that living beings develop based on the circadian rhythms that surround us, a series of oscillations of biological variables in repeated time intervals.

The biological clock of each organism (located primarily in the hypothalamus, specifically in the suprachiasmatic nucleus SCN) controls the actions and metabolism of the individual according to the specific moment in each of these circadian rhythms. For example, with light exposure, the SCN sends inhibitory signals to the pineal gland, which is responsible for synthesizing melatonin from tryptophan (and producing serotonin as an intermediate metabolite).

When the SCN perceives that daylight is beginning to decrease (20:00-22:00 H), through polysynaptic pathways it promotes the synthesis of melatonin in the pineal gland. The concentration of this hormone induces sleep in humans and its peak presence in the blood occurs at 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning. The presence of light (or its absence) completely modulates melatonin secretion.

This is the clearest example of how biological clocks are integrated with the circadian rhythm and also explains why we feel sleepier at night and receive continuous signals that we should sleep when the sun sets. In any case, this mechanism allows us to know how fatigue and the desire to rest are induced, but it does not explain why this physiological process has been established in the evolution of living beings over time.

Why we sleep (and we need to)

To understand the importance of the dream, just go to the principle of Ockham’s razor: “other things being equal, the simplest explanation is usually the most probable.” If living beings sleep, it is because it is necessary, it is that simple. We develop the idea a little: if rest were an anecdotal adaptation in the animal kingdom, the following postulations should be fulfilled:

None of these rules are followed. Although there are living beings that are constantly in flight or swimming, it is worth noting that many of them achieve this through unihemispheric sleep that is, thanks to a slow-wave brain rest that only occurs in half of the brain (the eye opposite the awake hemisphere remains open).

On the other hand, some species of birds do rest both hemispheres at the same time, but in periods of 5 seconds, while they are in the gliding phase of flight. Giraffes, many fish, and other animals also rest while standing or moving, for exceptionally short periods. With these data, one idea is clear to us: all neurologically complex animals sleep, in one way or another.

So, we sleep because our ancestors slept, because All vertebrates sleep and because sleeping is an adaptive character in the animal kingdom that cannot be discarded or modified If we get philosophical, we sleep because life with a nervous system is not conceivable without the rest it requires.

The physiological effects of sleep

The act of sleeping is a universal trait and, therefore, it must have some beneficial effect on the beings who practice it. First of all, it should be noted that sleep allows the brain to rest, since the body’s basal metabolism decreases during rest. The brain consumes about 350 kilocalories every 24 hours simply by existing (20% of the body’s energy), so it takes time to restore itself.

“Sleep is of the brain, by the brain and for the brain.” Sleep is explained by the brain, it is produced by the brain and it is for the brain. (Hobson JA, 2005)

This statement is justified with a very well documented physiological event: Cellular metabolism produces reactive oxygen species (ROS), very small, highly reactive molecules that damage the cell’s DNA and oxidize polyunsaturated fatty acids, among other harmful mechanisms. There are many antioxidants that more or less prevent this process, but one of the keys to aging at the cellular level is exposure to ROS, a product of your own metabolism.

When the brain is not constantly integrating information, metabolic rates are reduced and, therefore, the production of reactive oxygen species also decreases Thus, neuronal and accessory cells are less exposed to physiological stress and give them time to recover. Aging and damage to cells as a result of life itself cannot be avoided, but it is possible to delay it by reducing metabolic rates, at least during a significant part of the day.

We tend to have an anthropocentric view of things and, therefore, we believe that sleep really occurs so that we can integrate the information we have learned during the day. We ask you the following question: why does a fish of a given species (which does not present learned inheritance or complex social constructions) also rest, if it does not need to consolidate the learned information because it is not even capable of retaining it?

Based on this question, it only remains to think that the use of sleep to consolidate the information received is an effect derived from the sleep phase, but not the main reason we sleep**. If this were so, only animal species with the capacity to learn and retain experiences would sleep.

Dream and selection

At this point, it should be noted that the forces of natural selection that act on the world’s species do not favor longevity for the sake of it. If the dream exists, it is not to allow the animal to live longer without meaning, but so that it acts as accurately as possible during its lifespan and can reproduce as much as it can before dying.

For example, in rats, the total absence of sleep is fatal in 100% of cases at 3 weeks. Members of this species who do not sleep appear weakened, with slow reflexes, metabolic problems and even ulcers in their tissues. The “No-rest” state drastically decreases the survival of the animal, and therefore, of the entire species. For this reason, the trait of “not sleeping” has never been established in populations, despite the fact that there are certain disorders that cause it. Anything that is maladaptive is discarded into nature.

Summary

Thus, we dare to conclude that we sleep due to a mere mechanism of biological selection. If a living being does not sleep, it dies, does not reproduce and the species becomes extinct, so heritable characteristics that favor balanced sleep in living beings will always be favored.

For this reason, heritable pathologies that prevent sleep (such as fatal familial insomnia) are extremely rare in the general population and do not spread. People who carry them die and do not reproduce, so the trait does not spread. In short, we sleep because rest delays senescence and allows us (at an evolutionary level) to recover from the metabolic damage generated by the functioning of the cells themselves.