Traditionally, human beings have understood language as a means of communication through which it is possible to establish a connection with the world and allows us to express what we think or feel.

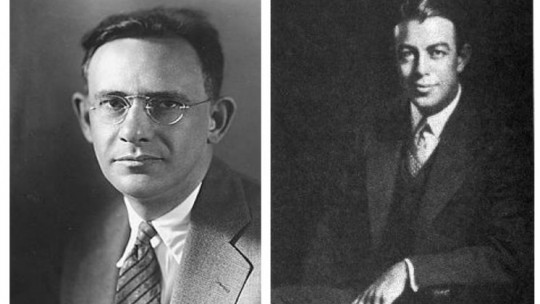

This conception sees language as a means of expression of what is already within. However, for the Sapir-Whorf theory of language, this has a much greater importance having a much more important role in organizing, thinking or even perceiving the world.

And although the relationship between thought and language has been an area of study that has received a lot of interest from psychologists and linguists, few theories have gone so far when it comes to relating these two worlds.

When language shapes thought

According to the Sapir-Whorf theory of language, human communication at a verbal level, the use of language in humans, It is not limited to expressing our mental contents For this theory, language plays a highly relevant role in shaping our way of thinking and even our perception of reality, determining or influencing our vision of the world.

In this way, the grammatical categories in which language classifies the world around us make us stick to a specific way of thinking, reasoning and perceiving, this being linked to the culture and communicative context in which we are immersed throughout. throughout childhood. In other words, the structure of our language It makes us tend to use specific interpretive structures and strategies.

Likewise, the Sapir-Whorf theory of language establishes that each language has its own terms and conceptualizations that cannot be explained in other languages. This theory therefore emphasizes the role of the cultural context in providing a framework in which to develop our perceptions, so that we are able to observe the world within socially imposed margins

Some examples

For example, the Eskimo people are accustomed to living in cold environments with large amounts of snow and ice, possessing in their language the ability to discriminate between various types of snow. Compared to other peoples, this contributes to them being much more aware of the nature and context in which they live, being able to perceive nuances of reality that escape a Westerner.

Another example can be seen in some tribes in whose language there are no references to time. Such individuals have severe difficulties conceptualizing units of time Other peoples do not have words to express certain colors, such as orange.

A final, much more recent example can be found with the term umami, a Japanese concept that refers to a flavor derived from the concentration of glutamate and which for other languages does not have a specific translation, being difficult to describe for a Western person.

Two versions of the Sapir-Whorf theory

With the passage of time and the criticisms and demonstrations that seemed to indicate that the effect of language on thought is not as modulatory of perception as the theory initially stipulated, The Sapir-Whorf theory of language has undergone some later modifications That is why we can talk about two versions of said theory.

1. Strong hypothesis: linguistic determinism

Sapir-Whorf’s initial view of language theory had a very deterministic and radical view regarding the role of language. For the strong Whorfian hypothesis, language completely determines our judgment capacity for thought and perception, giving them form and it can even be considered that thought and language are essentially the same.

Under this premise, a person whose language does not contemplate a certain concept will not be able to understand or distinguish it. As an example, a town that does not have any word for the color orange will not be able to distinguish one stimulus from another whose only difference is color. In the case of those who do not include temporal notions in their speech, they will not be able to distinguish between what happened a month ago and what happened twenty years ago, or between present, past or future.

Evidence

Various subsequent studies have shown that the Sapir-Whorf theory of language is not correct, at least in its deterministic conception experiments and research being carried out that reflect its falsehood at least partially.

Ignorance of a concept does not imply that it cannot be created within a given language, something that would not be possible under the premise of the strong hypothesis. Although a concept may not have a specific correlation in another language, it is possible to generate alternatives.

Continuing with the examples from previous points, if the strong hypothesis were correct, the peoples who do not have a word to define a color they would not be able to distinguish between two identical stimuli except in that aspect, since they could not perceive the differences. However, experimental studies have shown that they are fully capable of distinguishing these stimuli from others of a different color.

Likewise, we may not have a translation for the term umami, but we are able to detect that it is a flavor that leaves a velvety sensation in the mouth, leaving a long and subtle aftertaste.

Likewise, other linguistic theories, such as Chomsky’s, have studied and indicated that although language is acquired through a long learning process, there are partially innate mechanisms that before language as such emerges allow us to observe communicative aspects and even the existence of concepts in babies, being common to most known peoples.

2. Weak hypothesis: linguistic relativism

The initial deterministic hypothesis was, over time, modified due to the evidence that the examples used to defend it were not completely valid nor did they demonstrate a total determination of thought by language.

However, the Sapir-Whorf theory of language has been developed in a second version, according to which although language does not determine per se thought and perception, but yes It is an element that helps shape and influence in the type of content that receives the most attention.

For example, it is proposed that the characteristics of spoken language can influence the way in which certain concepts are conceived or the attention that certain nuances of the concept receive to the detriment of others.

Evidence

This second version has found some empirical demonstration, since it reflects that the fact that a person finds it difficult to conceptualize a certain aspect of reality because their language does not contemplate it means that they do not focus on said aspects.

For example, while a Spanish speaker tends to pay close attention to verb tense, others like Turkish tend to focus on who performs the action, or English on spatial position. Thus, each language favors highlighting specific aspects, which when acting in the real world can provoke slightly different reactions and responses. For example, it will be easier for the Spanish speaker to remember when something has happened than where, if they are asked to remember it.

It can also be observed when classifying objects. While some people will use shape to catalog objects, others will tend to associate things by their material or color.

The fact that there is no specific concept in language means that even if we are able to perceive it, we do not tend to pay attention to it. If for us and our culture it is not important whether what happened happened a day ago or a month ago, if we are asked directly when it happened it will be difficult for us to give an answer since it is something we have never thought about. Or if we are presented with something with a strange characteristic, such as a color that we have never seen, it may be perceived but it will not be decisive when making distinctions unless coloration is an important element in our thinking.

- Schaff, A. (1967). Language and Knowledge. Grijalbo Editorial: Mexico.

- Whorf, B. L. (1956). Language, Thought and Reality. The MIT Press, Massachusetts.