Creativity is a human psychological phenomenon that has favorably served the evolution of our species, just like intelligence. In fact, for a long time, they have become confused.

At the moment, It is argued that creativity and intelligence have a close relationship, but they are two different dimensions of our psychic world; Highly creative people are not necessarily more intelligent, nor are those with a high IQ more creative.

Part of the confusion about what creativity is is due to the fact that, For centuries, creativity has been covered with a mystical-religious halo For this reason, practically until the 20th century, the study of it has not been addressed scientifically.

Even so, since ancient times, it has fascinated us and we have strived to try to explain its essence through philosophy and, more recently, by applying the scientific method, especially from Psychology.

Creativity in Antiquity

Hellenic philosophers tried to explain creativity through divinity They understood that creativity was a kind of supernatural inspiration, a whim of the gods. The creative person was considered an empty vessel that a divine being filled with the inspiration necessary for them to create products or ideas.

For example, Plato maintained that the poet was a sacred being, possessed by the gods, who could only create what his muses dictated to him (Plato, 1871). From this perspective, creativity was a gift accessible to a select few, which implies an aristocratic vision of it that will last until the Renaissance.

Creativity in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages, considered an obscurantist period for the development and understanding of human beings, arouse little interest in the study of creativity. It is not considered a time of creative splendor so there was not much effort in trying to understand the mechanism of creation.

In this period, man was completely subordinated to the interpretation of the biblical scriptures and all his creative production was aimed at paying tribute to God. A curious fact about this time is the fact that many creators refused to sign their works, which showed the denial of their own identity.

Creativity in the Modern Age

In this stage, the divine conception of creativity is blurring to give way to the idea of the hereditary trait Simultaneously, a humanistic conception emerges, from which man is no longer a being abandoned to his destiny or to divine designs, but co-author of his own future.

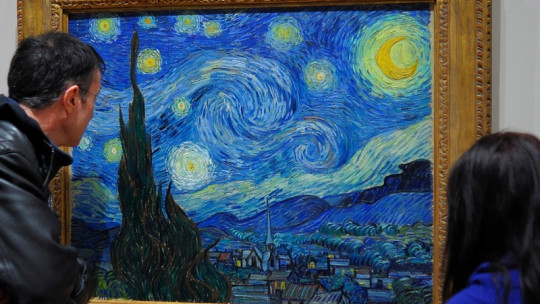

During the Renaissance the taste for aesthetics and art was resumed, the author recovered the authorship of his works and some other Hellenic values. It is a period in which the classic is reborn. Artistic production is growing spectacularly and, consequently, interest in studying the mind of the creative individual is also growing.

The debate on creativity, at this time, focuses on the duality “nature versus nurture” (biology or nurture), although without greater empirical support. One of the first treatises on human ingenuity belongs to Juan Huarte de San Juan, a Spanish doctor who in 1575 published his work “Examen de ingenios para las Ciencias”, precursor of Differential Psychology and Professional Guidance. At the beginning of the 18th century, thanks to figures such as Copernicus, Galileo, Hobbes, Locke and Newton, Confidence in science grows while faith in the human ability to solve its problems through mental effort grows Humanism is consolidated.

The first relevant modern research on the creative process took place in 1767 by William Duff, who analyzed the qualities of original genius, differentiating it from talent. Duff maintains that talent is not accompanied by innovation, while original genius is. The points of view of this author are very similar to recent scientific contributions, in fact, he was the first to point towards the biopsychosocial nature of the creative act, demystifying it and anticipating two centuries to the Biopsychosocial Theory of Creativity (Dacey and Lennon, 1998).

On the contrary, during this same time, and fueling the debate, Kant understood creativity as something innate a gift of nature, which cannot be trained and which constitutes an intellectual trait of the individual.

Creativity in postmodernity

The first empirical approaches to the study of creativity did not occur until the second half of the 19th century, by openly rejecting the divine conception of creativity. Also influential was the fact that at that time Psychology began its split from Philosophy, to become an experimental science, which is why the positivist effort in the study of human behavior increased.

During the 19th century, the concept of hereditary trait predominated. Creativity was a characteristic trait of men and it took a long time to assume that creative women could exist. This idea was reinforced by Medicine, with different findings on the heritability of physical traits. A passionate debate between Lamarck and Darwin about genetic inheritance captured scientific attention for much of the century. The first argued that learned traits could be passed between consecutive generations, while the Darwin (1859) showed that genetic changes are not so immediate nor the result of practice or learning, but rather occur through random mutations during the phylogeny of the species, which requires large periods of time.

Postmodernism in the study of creativity could be located in the works of Galton (1869) on individual differences, greatly influenced by Darwinian evolution and the associationist current. Galton focused on the study of the hereditary trait, ignoring psychosocial variables. Two influential contributions stand out from him for later research: the idea of free association and how it operates between the conscious and the unconscious, which Sigmund Freud would later develop from his psychoanalytic perspective, and the application of statistical techniques to the study of individual differences. that They make him a bridge author between the speculative study and the empirical study of creativity

The consolidation phase of Psychology

Despite Galton’s interesting work, psychology in the 19th and early 20th centuries was interested in simpler psychological processes, following the path marked by Behaviorism, which rejected mentalism or the study of unobservable processes.

The behaviorist domain postponed the study of creativity until the second half of the 20th century, with the exception of a couple of lines that survived positivism, Psychoanalysis and Gestalt.

The Gestalt vision of creativity

The Gestalt provided a phenomenological conception of creativity It began its journey in the second half of the 19th century, opposing Galton’s associationism, although his influence was not noticed until well into the 20th century. The Gestaltists argued that creativity is not a simple association of ideas in a new and different way. Von Ehrenfels first used the term gestalt (mental pattern or form) in 1890 and based his postulates on the concept of innate ideas, as thoughts that originate completely in the mind and that do not depend on the senses to exist.

Gestalts maintain that creative thinking is the formation and alteration of gestalts, whose elements have complex relationships forming a structure with a certain stability, so they are not simple associations of elements. They explain creativity by focusing on the structure of the problem, stating that the mind of the creator has the ability to move from some structures to more stable ones. Thus, the insightor spontaneous new understanding of the problem (aha! or eureka!) phenomenon, occurs when a mental structure is suddenly transformed into a more stable one.

This means that creative solutions are usually obtained by looking at an existing gestalt in a new way, that is, when we change the position from which we analyze the problem. According to Gestalt, When we obtain a new point of view on the whole, instead of reorganizing its elements, creativity emerges

Creativity according to psychodynamicists

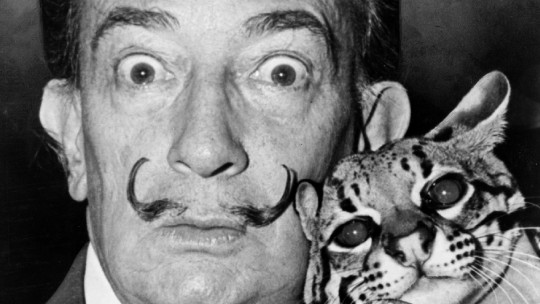

Psychodynamicists made the first major effort of the 20th century in the study of creativity. From Psychoanalysis, creativity is understood as the phenomenon that emerges from the tension between conscious reality and the unconscious impulses of the individual. Freud maintains that writers and artists produce creative ideas to express their unconscious desires in a socially acceptable way so art is a compensatory phenomenon.

It contributes to demystifying creativity, by maintaining that it is not a product of muses or gods, nor a supernatural gift, but that the experience of creative enlightenment is simply the passage from the unconscious to the conscious.

The contemporary study of creativity

During the second half of the 20th century, and following the tradition started by Guilford in 1950, creativity has been an important object of study in Differential Psychology and Cognitive Psychology, although not exclusively in them. From both traditions, the approach has been fundamentally empirical, using historiometry, idiographic studies, psychometrics or meta-analytical studies, among other methodological tools.

Currently, the approach is multidimensional Aspects as diverse as personality, cognition, psychosocial influences, genetics or psychopathology, to name a few, are analyzed, as well as multidisciplinary, since there are many domains that are interested in it, beyond Psychology. Such is the case of Business studies, where creativity arouses great interest due to its relationship with innovation and competitiveness.

So, During the last decade, research on creativity has proliferated, and the offer of training and training programs has grown significantly. Such is the interest in understanding it that research extends beyond academia, and involves all types of institutions, including government ones. Its study transcends individual analysis, even group or organizational analysis, to address, for example, creative societies or creative classes, with indices to measure them, such as: Euro-creativity index (Florida and Tinagli, 2004); Creative City Index (Hartley et al., 2012); The Global Creativity Index (The Martin Prosperity Institute, 2011) or the Creativity Index in Bilbao and Bizkaia (Landry, 2010).

From Classical Greece to the present day, and despite the great efforts we continue to dedicate to analyzing it, We have not even managed to reach a universal definition of creativity, so we are still far from understanding its essence Perhaps, with new approaches and technologies applied to psychological study, such as the promising cognitive neuroscience, we can discover the keys to this complex and intriguing mental phenomenon and, finally, the 21st century will become the historical witness of such a milestone.