In 1907, Picasso finished his canvas Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Ladies of Avignon). Many see the beginning of cubism in the painting, although it is more of an almost experimental work, in which Picasso plays with various elements: faces that look like masks, “broken” and fragmented perspective, arbitrary colors… However, all of these Elements had already been used previously, so, in principle, they did not represent anything new in themselves.

Cubism itself would not be born until later, when, through the so-called analytical cubism, the forms were refined and the emotional subjectivity of painting was completely eliminated. But, let us start at the beginning. What is cubism? Let’s see it below.

Characteristics of cubism

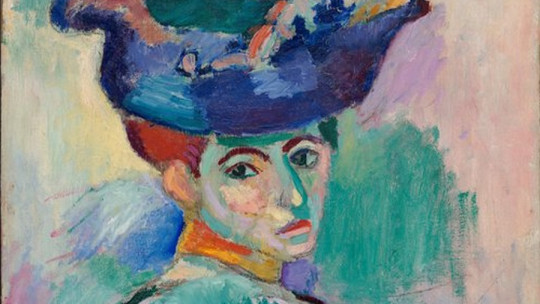

At the beginning of the 20th century, the avant-garde forces burst onto the European art scene. In 1905 we have the Fauves artists at the Salon d’Automne in Paris and, a few years later, the German Expressionists took the chromatic strength of these Fauves and created their own language. All these artists had in common their passion and the high emotional charge of their compositions.

Cubism, however, is something else. In fact, the cubists distance themselves from the expressionists and impressionists (occupied only with the subjectivity of the image) and focus on form and structure In this way, color, which had been so important for both the Impressionists and the Fauves, was relegated to a strict background: from now on, the Cubists were only going to be interested in the composition of the volumes.

The Cubists promulgated an “intellectual” art. In other words, an art that was not limited to recording reality, but also carefully structured it through meticulous purification that left only the essential elements. The painting had to come, therefore, from the “brain”, and not from emotion, as was the case with the expressionists. This new art would have, as Guillaume Apollinaire stated in his Aesthetic meditations (1913), geometry as a basis, in the same way that grammar was the basis of writing.

The background of cubism

As always, new art is not born from nothing. Artists influence each other and create aesthetic currents that constantly follow and reject each other, mold, adapt, and reinvent themselves. So, We find two painters who are clear antecedents of Cubism: Georges-Pierre Seurat (1859-1891) and Paul Cézanne (1839-1906)

From the first, the cubists took the concept of divisionism. In this sense, they were not the first: the Fauves had already been inspired by Seurat some years before. “Seuratian” divisionism advocated the approximation of colors without mixing them, so the person in charge of constructing the final image was the eye of the viewer. From the second, the cubists collected their interest in overcoming impressionism through solid painting of defined shapes, and also a certain geometrization of these shapes.

When it comes to understanding where Cubism emerged from, we cannot forget the historical context that shaped it. Thus, it is inseparable from scientific discoveries in subjects such as optics, physics and chemistry. Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity (1905) had a powerful impact on cubist artists since he questioned the validity of the concepts of space and time.

On the other hand, the rise of so-called “primitivism”, that is, the attraction to the artistic manifestations of the peoples of Africa or Oceania, especially influenced artists such as Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). Henri Matisse, the undisputed leader of the Fauves, had shown a young Picasso the magic of African masks, and his flattened and rotund forms would have a powerful influence on the work of the man from Malaga.

The two cubist stages

Art historians mainly distinguish two stages in Cubism: analytical cubism, which would develop between 1909 and 1910, and synthetic cubism, which would see the light at the end of 1910, once the first had already faded. To these two, let’s say, “canonical” stages, we could add a third, which would actually be the preamble to the other two, which we could call primitive or intuitive cubism. But let’s go in parts.

The beginnings of cubism

In 1907, a retrospective of Paul Cézanne, who died the previous year, was held at the Paris Autumn Salon. The exhibition impresses three young artists: Picasso, Georges Braque (1882-1963) and Fernand Léger (1881-1955). In Cézanne’s painting they saw the dawn of a new art, an art that disdained impressionistic transience and sought “real” art, lasting over time. The painter achieved this through certain formal inconsistencies: he represented all the planes of the object at the same time, and thus frozen in the painting its complete reality. Cézanne “broke” the form and restructured it. The Cubists would go further and completely destroy classical perspective. An object would no longer be seen from a single point of view, but from several at the same time.

Picasso and Braque, infected by the enthusiasm of this discovery, began to make attempts at what would be this new and “definitive” art. It is at this time that we must place The ladies of Avignon, where Picasso experiments with true vehemence. The works of this period are not yet analytical, and exude an intuitive passion that does not yet make them fully cubist.

analytical cubism

The next stage of cubism is the so-called analytical cubism. In this period the obvious emotion of previous years has been “overcome” and an exclusively “cerebral” execution is advocated. So, the object is definitively “broken”, it is dissected, it is analyzed All the planes of the object appear on the surface of the painting, joining and superimposing each other. Thus, the figure disappears and the viewer is unable to recognize what he is looking at. However, this is not an abstract painting: it is representing a motif, but in a different way than what we are used to.

Some examples of this analytical cubism are Portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1910), by Picasso, or the Woman with Mandolin (1910) by Georges Braque.

At this stage the color loses its privileged position and the tones focus on ochers and grays.

synthetic cubism

At the end of 1910, analytical cubism began to deteriorate and the second type of cubism, synthetic, gained strength. This second stage is characterized by the absence of analysis and, therefore, the “breakage” of the object, which are replaced by a summary of the same through the representation of several planes, in the manner of Cézanne. Furthermore, the color returns to the canvases with unusual force. Some examples from this period are Mandolin and guitar (1924), by Pablo Picasso, or The open window (1921), by Juan Gris (1887-1927), one of the most prominent painters of this period.

Synthetic cubism is famous for having introduced elements into art that, in principle, were foreign to it. Firstly, we have collage, that is, the introduction of real elements of everyday life in painting, of which the Still life with slatted chair, by Picasso, which is considered the first artistic collage. Secondly, the so-called collés papiers, papers glued to the fabric on which they painted; and, finally, the addition of typography in the paintings, like letters cut out of a magazine.

Cubism for posterity

It was during the stage of synthetic cubism when the foundations of cubist aesthetics were laid. In 1912, Jean Metzinger (1883-1956) and Albert León Gleizes (1881-1953) published From cubism, an essay that sought to lay the foundations on which the movement was sustained. However, is Aesthetic meditations. The cubist painters (1913) by Guillaume Apollinaire, the text that is considered a kind of manifesto of cubism

Finally, these artists would receive their name from the same person who baptized the movement. fauv: Louis Vauxcelles, art critic who, upon contemplating Braque’s work, declared that the painter “mistreated” the forms and reduced everything to “cubes.” Great character, this Vauxcelles: he carries the nomenclature of two avant-gardes behind him.