Although it may surprise some, Spain is a country with an extensive philosophical history. Modern Spanish philosophers may not have had as much impact abroad as Noam Chomsky, Simone de Beauvoir or Jürgen Habermas have had, but their approaches are certainly very interesting.

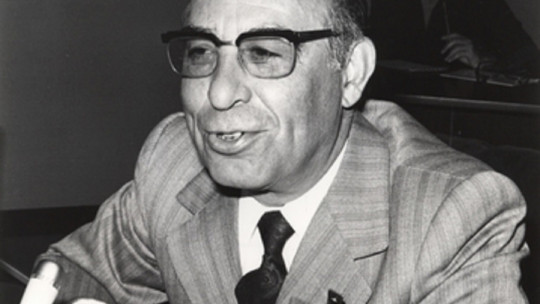

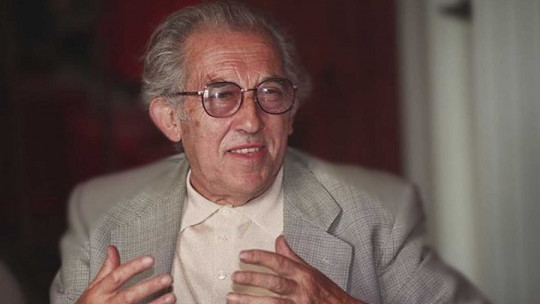

Gustavo Bueno has been one of the contemporary thinkers of the Spanish philosophical scene, with interesting visions about the ideas of the left and right, a clear defense of Spain as a great nation and creator of a philosophical system which he called philosophical materialism.

Below we will see the interesting life, thought, ideology and work of this Spanish philosopher, considered one of the greatest of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, through a biography of Gustavo Bueno

Brief biography of Gustavo Bueno

Gustavo Bueno Martínez was born in Santo Domingo de la Calzada, La Rioja, on September 1, 1924. His parents were Gustavo Bueno Arnedillo, a doctor, and María Martínez Pérez. In his youth he received a fundamentally Catholic education, which would allow him good knowledge of theology and the Christian roots of Spanish society.

His university life was spent at the prestigious universities of La Rioja, Zaragoza and Madrid. After completing his doctoral thesis as a scholarship holder at the CSIC (Higher Council for Scientific Research) In 1949, at only twenty-five years old, he obtained a professorship in Secondary Education It would be around that time that he would begin to work as a teacher at the Lucía de Medrano Institute in Salamanca, where he would work until 1960.

Gustavo Bueno became an apprentice to the Falangists Eugenio Frutos Cortés and Yela Utrilla while on scholarship at the Luis Vides Institute in Madrid, a place he had accessed thanks to his friendship with Rafael Sánchez Mazas. He also had the opportunity to receive knowledge from members of Opus Dei such as Raimundo Pániker and Rafael Gambra.

At the end of his teaching task at the Lucía de Medrano Institute in 1960 Gustavo Bueno He moved to Asturias, a land where he would settle permanently There he would serve as a professor in Fundamentals of Philosophy and History of Philosophical Systems at the University of Oviedo until almost the end of the century in 1998. It would be from that year on that he would found his Gustavo Bueno Foundation, having its headquarters in Oviedo from which would carry out intense work.

Since the 1970s, Bueno was developing his own philosophical system, which he would call philosophical materialism Furthermore, as the years went by he would acquire a vision clearly defending the idea of Spain as a great nation, with which, in addition to founding his own institution and exposing his national pride in his texts, Bueno was a member and honorary patron at the Foundation for the Defense of the Spanish Nation (DENAES).

In his last years he became involved in several controversies about his vision of Spain, the ideas of left and right, and religion. All of them made him gain a lot of fame during the 2000s, for better or worse, and became quite a media personality, something quite remarkable in Spain since rarely does a philosopher have such an impact in the Iberian media.

Gustavo Bueno Martínez He died on August 7, 2016 in Niembro Asturias, at the age of 91 He died two days after his wife Carmen Sánchez died. He was the father of Gustavo Bueno Sánchez, also a philosopher.

philosophical materialism

The philosophical materialism proposed by Gustavo Bueno has something in common with traditional materialism. the denial of spiritualism, that is, the denial of the existence of spiritual substances However, one should not think that he reduces his philosophy to corporealism, as is often the case in other materialisms. Bueno’s philosophical materialism admits the reality of incorporeal material beings such as, for example, the real (non-mental) relationship of the distance that can exist between two physical objects, such as two glasses. The distance between those two vessels is incorporeal, it exists, but it is not spiritual.

Among the widely developed ideas that can be found within Bueno’s philosophical materialism, we can highlight the following four:

These were the most recurring themes in Bueno’s work until the 90s. However, At the beginning of the new millennium he began to delve into topics related to ethics and social and political criticism The way in which she presented these new topics has been criticized since he did not present them with the same rigor as the previous ones. For example, it has been said that his criticism of pacifism is more a way of disqualifying than actually expressing a well-founded opinion.

Among other themes that can be found in Bueno’s work in the early 2000s we can find:

His ideology

If Gustavo Bueno was quite controversial when expressing his philosophical visions, the way he did it with his political ideology was no less. He was a pupil of the national-syndicalist Santiago Montero Díaz whose ideological trajectory led him to embrace a mix between right-wing and left-wing totalitarianism at the end of the Franco regime, coming to show sympathy for different paratotalitarian political projects, including the Soviet Union.

He was widely recognized for his Europhobic views He used to state that Europe was the problem and Spain the solution, seeing the old continent as a source of danger for the survival of the Spanish nation. The idea that Europe could be the natural place for Spain’s international projection seemed terrifying to him.

He was more in favor of continuing the legacy of the Spanish Empire and promoting the idea of Hispanidad. In his works exposes the idea of predatory and generating empires with Spain being in this second category.

It should be said that throughout his life Gustavo Bueno was not a person with a fixed or obvious political ideology. The only thing it seems like he was well pigeonholed in was being a Spanish nationalist. In the rest of the topics he spoke about, he showed somewhat variant opinions, such as considering himself a Catholic atheist, in the sense that he did not profess any religion but recognized the importance of the Catholic faith in Spanish culture; and heterodox Marxist, criticizing vulgar Marxism and promoting a recovery of more classical Marxism.

Also He has been considered a non-believing Thomist, being a defender of the Spanish scholastic tradition already begun in times as ancient as those of the Toledo School of Translators of the 13th century He has also been classified as a Platonist, comparing himself to Plato’s own Academy and being a good connoisseur of it.

Its location within the political spectrum is not at all fixed. One might think that being a Spanish nationalist he would have embraced right-wing and ultra-right theses, an aspect that seems to be partly true at the end of his life.

Nevertheless, He has also been considered left-wing, rejecting right-wing particularism, although no less critical of the Spanish left In his last years he was publicly supportive of the Spanish Popular Party, supporting the candidacy of President Mariano Rajoy.

It is considered that Bueno’s philosophy and his homonymous foundation have served as an ideological reference, in one way or another, for the formation of the Vox party. Many of the similarities between Bueno’s school and the extreme right party are notable, and it is considered that many of the keys that mark Santiago Abascal’s party are the same ones that Bueno always defended.

Controversies

It is not surprising that a person as controversial as Gustavo Bueno was would maintain several controversies throughout his life, both with the left, the right, atheism, Catholics, Maoists… His ideas about the Spanish nation, the Christian faith and the role of the right and the left aroused many blisters in broad Spanish philosophical sectors There are so many controversial episodes surrounding his person that he practically gave us to make a schedule with each year from the time he finished his university studies until his death.

On December 1, 1970, some Maoist students from the Proletarian Communist Party of Barcelona threw a can of paint at him, attacked him and tried to put a sign on him that said “lackey of capitalism.” They were protesting not because of their Falangist friendships or controversial opinions about Spain. They were protesting because Bueno positioned himself in favor of the USSR, a communist regime, against China, another communist regime. Seven years later the aggression would come from the other side of the political spectrum, this time being the right-wing group AAA (Alliance Apostolic Anti-Communist) setting fire to his SUV.

In 1989 started a strong discussion in the program “La Clave” by José Luis Balbín on Spanish Television There he argued with a Jesuit about the supposed miracle of Fatima, accusing the religious that he did not know his own religious dogma and telling him that this miracle was truly absurd.

In 2003 published “The myth of the left” in which he earned the enmity of several pro-independence groups in Spain They accused him of being a fascist, and so did several political scientists who criticized his theory of the generations of the left. Ironically, he was also accused of being a Stalinist for attempting, according to his detractors, to create a great alliance between liberals, communists and Catholics against social democracy.

In 2007 he became involved in another controversy, this time coming from the hand of Andalusian independentists, who described him as conservative and Islamophobic after criticizing the designation of Blas Infante in the new Andalusian Statute of Autonomy as the father of the Andalusian homeland. Furthermore, some statements he made after the jihadist attack on the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001, statements in which he stated that the roots of Islam had to be destroyed came to light.

He tried to qualify by saying that he was not attacking the Muslim religion itself, nor was he blaming all of Islam for the terrorist attacks. However, he did clarify that it is typical of Islam and Buddhism to immolate for religious reasons, something in his eyes quite typical of less thoughtful religious fanaticism. Furthermore, he said that when he spoke of destroying the roots of Islam he was saying it in the same sense as philosophical rationalism with Christian ideological roots did in the 17th and 18th centuries

Among his other controversies are having been considered to be an apology for gender violence, being against abortion, considering the animal rights movement absurd and granting any rights to animals, and also considering people in favor of historical memory. and the recovery of the bodies of his relatives who died during the Spanish Civil War “obsessed by bones.”