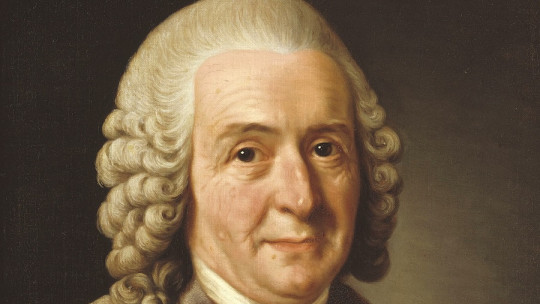

Known as the greatest taxonomist of all time, Carl von Linné’s life is that of an explorer of his own country. Born into a family of Lutheran pastors, the young man did not want to dedicate himself to the family profession, focusing his attention on the sciences.

As if he were a discoverer of the New World, Carl von Linné was in charge of describing every plant, animal or even culture that was found in the dark forests of his Scandinavian nation, gradually developing the binomial classification system that today Today it is still used by the scientific community.

Next we will discover the life of this peculiar Swedish botanist and naturalist, who made his native Sweden the center of botany and taxonomy studies, through a biography of Carl von Linné

Brief biography of Carl von Linné

Carl Nilsson Linnæus, known as Carl von Linné or Carlos Linnaeus, born on May 23, 1707 in Råshult, Sweden. He was the son of Nils Ingemarsson, a Lutheran pastor passionate about plants, and Christina Brodersonia, daughter of a Protestant pastor.

Early years

At the age of two, he moved with his parents to Stenbronhult, a region located in the south of Sweden characterized by being especially green and full of all types of plant species. There, his father began to structure and care for the garden of the local church, enriching it with plants from other regions. Thus, young Carl learned a love of plants from his childhood and continued this passion inherited from his father to dedicate himself to the study of botany and animals.

In 1716, Carl began his Latin studies at Vaxjö Cathedral. From a young age he showed interest in natural sciences and knowledge of species, which made him start collecting plants and insects. His Latin studies helped him deepen scientific knowledge since Plutarch’s language was the vehicle for transmitting the highest knowledge of the time.

It was at this time that had the opportunity to meet Johan Rothman, an experienced botanist who introduced young Carl to the Tournefort classification system, a system that organized plants according to the corolla of their flowers. He also had the opportunity to learn about Sébastien Vaillant’s work on plant reproduction as well as have access to Herman Boerhaave’s “Institutiones medicae”.

Since his childhood, the young Carl Linnæus was fascinated by everything related to the structure and reproduction of plants. Although he had grown up in a family with a long religious lineage, the young man did not show a religious vocation and preferred to dedicate himself to the world of natural sciences. In 1727 he began his studies in medicine at the University of Lund at the age of twenty, although that discipline did not arouse great interest in him as searching for insects and plants around his university residence did.

This interest in plants and animals caught the attention of Kilian Strobaeus, a man who lived in Lund and who owned an extensive library. Strobaeus gave young Linnaeus permission to consult his library, something that had a huge impact on young Carl’s life. It would be this experience that would motivate him in his vocation as a naturalist.

After the first year studying at Lund University he was transferred to Uppsala University, which at that time was the main educational center in Sweden.

First expedition

To move forward, the young Carl von Linné He dedicated himself to teaching botany classes to be able to support himself financially Despite his precarious economic condition, Linnaeus was able to cover the costs of what would end up being his first botanical and ethnological expedition in Lapp lands around 1731. Using only a horse, a few coins, a notebook and a pencil, the young man entered in the unknown and dark Nordic forests.

On his journey through Lapland, a region that includes the north of present-day Norway, Sweden and Finland, Carl von Linné was able to discover hundreds of species that had never before been scientifically cataloged Although he had not left his own country, Linnaeus felt like a true explorer of the New World, only he did it in Sweden itself.

Coupled with his compulsive obsession with wanting to have everything well organized and meticulously named, Linnaeus began his titanic task of naming and classifying every specimen, animal or plant, that crossed his path. In addition, he had the opportunity to learn what the Saami people were like, that is, the different Lapp cultures of the region. The work of this era is not only that of a great naturalist but also that of a thorough and careful anthropologist.

His observations and findings in Lapp lands would help him, years later, to publish one of his most important works: “Flora Lapponica.” The studies and data presented in this document aroused the interest of the Swedish scientific community and also that of other places in Europe. His travels through Lapland also motivated him to study minerals in more depth and also propose a classification system for rocks and crystals.

Second expedition

After the success of his first expedition through Lapland, which had helped him discover a whole new world within his own country, Linnaeus decided to embark on a second expedition in 1734. This time he would do so accompanied by ten volunteers with whom he would dedicate himself to explore and study the flora of the Dalarna region, in central Sweden. This expedition had the financial contribution of the governor of that region and resulted in the publication of “Iter Dalecarlicum”.

In 1735 he had the opportunity to meet the family of Dr. Johan Moraeus, paying special attention to his daughter Sara Lisa. Linnaeus asked Moraeus for the hand of her daughter, and although the doctor granted it, he made it a condition precedent to marriage that she finish her studies in medicine once and for all. Thus, Charles Linnaeus He decided to travel to Holland to finish his degree in medicine at the University of Harderwijk in the spring of 1735 There he received his doctorate by presenting a thesis in which he spoke about the origins of malaria: “Febrium intermitentium Causa”

Later he would move to Leiden, a place that would see several of his most important works published, among which was “Flora Lapponica” (1737). It would also be here where he would obtain from the senator of that city the necessary financing to publish his most important work: “Systema naturae” (1735).

While still in the Netherlands, Carl von Linné had the opportunity to meet great Dutch botanists, including Jan Frederik Gronovius and George Clifford III, a wealthy plant lover, who commissioned him to reorganize and care for his private botanical garden. It would be from this work that his work “Hortus Cliffortianus” would be born (Clifford’s Garden1737), in which he studies and classifies his rich friend’s plants.

Other works that he would publish in Holland were “Fundamenta Botanica” and “Bibliotheca Botanica”. In 1737 he published “Critica Botanica”, “Genera Plantarum”, “Hortus Cliffortianus” and “Flora Lapponica”. Shortly before leaving Holland, in 1738, he published “Classes Plantarum.” In these works shows his particular system of classifying plants, in which he uses the characteristics of the reproductive organs of plants as criteria

In 1736 he traveled to Oxford and met prominent English naturalists, including the great botanist JJ Dillenius. He also took the opportunity to visit France and, shortly after, he would become the eighth foreign member of the Paris Academy of Sciences. His influence in the scientific world was booming and thanks to his travels he was able to exchange specimens of plants and animals. He also obtained seeds to reproduce in his many botanical gardens that he had founded.

In 1738 he returned to Sweden where, practicing as a doctor, he studied and specialized in the treatment of syphilis At Uppsala University he is awarded for his work in medicine, in addition to receiving the task of reorganizing the botanical garden of that same university. Linnaeus would take advantage of this opportunity to apply his now famous binomial taxonomic system.

Professional expeditions

In 1739 he promoted the creation of the Stockholm Academy of Sciences, of which he was its first president. In 1741 he was appointed professor of medical practice at the University of Uppsala and, the following year, he was assigned the chair of botany, dietetics and materia medica, titles much more in line with the already extensive practical knowledge that he possessed. Holding these chairs, Linnaeus would make Uppsala University the center of botany study in Europe

Linnaeus’ scientific findings resonated throughout Swedish society to such an extent that the political group of the “hattar” (“hatters” in Swedish) began to encourage and support the commercial and scientific expeditions promoted by the naturalist. Sweden was in full imperialist expansion, and had a great interest in establishing trade independent of the rest of Europe. That is why the Swedish bourgeoisie began to support any expedition that involved the discovery of a new trade route to any region rich in resources.

Linnaeus He played a decisive and influential role in the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Taking advantage of his managerial position, he made contacts with the Swedish East India Company with the intention of obtaining the necessary financial support to organize his botanical expeditions to inhospitable regions. Not only did he want to thoroughly document all the animal and plant species of Sweden, but also those of the rest of Europe and, if possible, the entire world.

It is then that Linnaeus decides to recruit a group of young students, whom he would baptize as the “apostles”, to help him on his multiple worldwide expeditions. They would visit all the places there were and to be, both under the command of Linnaeus himself and under the direction of other great explorers such as James Cook.

Despite its commercial and scientific success The expeditions promoted by Linnaeus were very dangerous Many of the young students who made up the “apostles” ended up dying or falling prey to madness due to the harshness of the expeditions. Moving away from mother Sweden was already risky, but ending up in unknown territories of South America or Asia was, on many occasions, visiting hell itself.

The Linnaean System in taxonomy

We owe the current binomial system for classifying species to Carlos Linnaeus. We have the first ideas of his theory for this system around 1730, when Linnaeus had already developed his own system of classifying plants based on the observations made by Vaillant on the reproductive organs of flowering plants. Linnaeus He believed that morphology was the perfect basis for organizing botanical systems and applied it in his naturalistic task

As new species were discovered and described, their classification system changed. He strove to create a system as natural and close to reality itself and, although timidly, his writings suggest certain evolutionary beliefs. Although at first he believed that the species of the earth had been unchanged since Creation, he later changed his mind considering that, through hybridization and cross-pollination, he could create new plant “species.”

His most important work in botanical terms is “Species Plantarum”, published in 1753 This book, which is a compilation of all of his theoretical and practical work in the field, took him more than five years to write and he believed that he would never see it finished. In it he definitively establishes his binomial system to order plants, based on their theoretical similarity with other species and the characteristics of the variety. He gave names to 8,000 plants.

Linnaeus’ binomial system consists of giving two Latin names to each species, constituting its scientific name. The first word, beginning with a capital letter, refers to the genus, while the second refers to the species or subspecies of the plant, animal or any other specific organism. Both words are in Latin or are Latinized words from non-Roman languages.

This system was so functional that it didn’t take long to catch on. In addition, it allowed giving more “surnames” to the species, establishing other taxa superior to the genus that allowed us to specify more specifically what the location of the species was in the phylogenetic tree Naturally, this idea was very advanced for the time and each taxon has been refined over the last 300 years.

For example, the scientific and binomial name of the wolf is “Canis lupus”. “Canis” is the common genus with other species, such as the fox. The taxonomic pyramid in which the wolf is found is as follows.

Also, each species could be grouped into subspecies In the case of the dog we have “Canis lupus familiaris”. This name refers to the fact that, in fact, dogs and wolves are part of the same species, but the dog has its own characteristics that make it so different from its wild relative that it is almost another species.

Last years

His last years were spent in Sweden as a professor of medicine and botany. In 1758 moved to a residence near Hammarby In 1762 he received the title that gave him the rank of nobleman for his scientific merits, since with his work he had managed to turn the cold and apparently un-European Sweden into a true scientific center. This is the moment when Carl Nilsson Linnæus would officially be called Carl von Linné.

In the early 1770s Carl von Linné’s forces began to fade. During the spring of 1774 he was the victim of a stroke from which he recovered with some after-effects. He would progressively become paralyzed and lose his memory, being unable to recognize the most common and simple of plants. The greatest classifier of living species was no longer capable of classifying anything. Carl von Linné died on January 10, 1778, at the age of 70.