Today, national and international associations of Psychology have a code of ethical conduct that regulates practices in psychological research.

Experimenters must comply with various standards regarding confidentiality, informed consent, or beneficence. Review committees are charged with enforcing these standards.

The 10 most chilling psychological experiments

But these codes of conduct have not always been so strict, and many experiments from the past could not have been carried out today because they violated some of the fundamental principles. The following list compiles ten of the most famous and cruel experiments in behavioral science

10. Little Albert’s Experiment

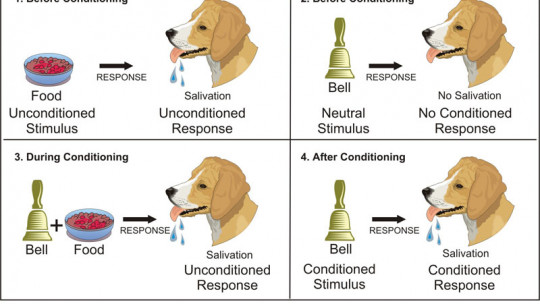

At Johns Hopkins University in 1920, John B. Watson carried out a study of classical conditioning, a phenomenon that associates a conditioned stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus until they produce the same result. In this type of conditioning, a response can be created in a person or animal toward an object or sound that was previously neutral. Classical conditioning is commonly associated with Ivan Pavlov, who rang a bell every time he fed his dog until the mere sound of the bell caused his dog to salivate.

Watson tested classical conditioning on a 9-month-old baby he called Albert Little Albert began loving the animals in the experiment, especially a white rat. Watson began to pair the presence of the rat with the loud sound of metal hitting the hammer. Little Albert began to develop a fear of the white rat, as well as most animals and furry objects. The experiment is considered particularly immoral today because Albert was never sensitive to the phobias that Watson produced in him. The boy died of an unrelated illness at age 6, so doctors could not determine whether his phobias would have persisted into adulthood.

9. Asch’s conformity experiments

Solomon Ash He experimented with conformity at Swarthmore University in 1951, putting one participant in a group of people whose task was to equalize the lengths of a series of lines. Each individual had to announce which of three lines was closest in length to a reference line. The participant was placed in a group of actors who were told to give the correct answer twice and then switch by saying the incorrect answers. Asch wanted to see if the participant would conform and give the wrong answers knowing that otherwise he would be the only one in the group to give the different answers.

Thirty-seven of the 50 participants agreed that the answers were incorrect despite physical evidence otherwise. Asch did not ask for informed consent from the participants, so today, this experiment could not have been carried out.

8. The bystander effect

Some psychological experiments that were designed to test the bystander effect are considered unethical by today’s standards. In 1968, John Darley and Bibb Latané They developed an interest in witnesses who did not react to crimes. They were especially intrigued by the murder of Kitty Genoves, a young woman whose murder was witnessed by many, but none prevented it.

The pair conducted a study at Columbia University in which they presented a participant with a survey and left him alone in a room to fill it out. A harmless smoke began to seep into the room after a short period of time. The study showed that the participant who was alone was much faster in reporting the smoke than participants who had the same experience but were in a group.

In another study by Darley and Latané, subjects were left alone in a room and told that they could communicate with other subjects via an intercom. In reality, they were just listening to a radio recording and he had been told that his microphone would be turned off until it was his turn to speak. During the recording, one of the subjects suddenly pretends to be having a seizure. The study showed that The time it took to notify the researcher varied inversely with respect to the number of subjects In some cases the researcher was never notified.

7. Milgram’s obedience experiment

The Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram I wanted to better understand why so many people participated in such cruel acts during the Nazi Holocaust. He theorized that people generally obey authority figures, which raised the questions: “Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Or, could we consider them all complicit?” In 1961, obedience experiments began.

The participants thought they were part of a memory study. Each trial had a pair of individuals divided into “teacher and student.” One of the two was an actor, so there was only one real participant. The research was manipulated so that the subject was always the “teacher.” The two were placed in separate rooms and the “master” was given instructions (orders). He or she pressed a button to penalize the student with an electric shock every time he gave an incorrect answer. The power of these shocks would increase each time the subject made a mistake. The actor began to complain more and more as the study progressed until he was screaming from the supposed pain. Milgram found that most participants complied with orders by continuing to deliver shocks despite the “trainee’s” obvious distress

If the alleged discharges had existed, the majority of subjects would have killed the “student.” When this fact was revealed to the participants after the study concluded, it is a clear example of psychological damage. Currently it could not be carried out for that ethical reason.

6. Harlow’s primate experiments

In the 1950s, Harry Harlow, from the University of Wisconsin, researched childhood dependency using rhesus monkeys instead of human babies. He took the monkey away from his real mother, who was replaced by two “mothers,” one made of cloth and one made of wire. The cloth “mother” served no purpose other than the comfortable feeling of it, while the wire “mother” fed the monkey through a bottle. The monkey spent most of its time next to the cloth mother and only about an hour a day with the wire mother despite the association between the wire pattern and food.

Harlow also used intimidation to prove that the monkey found the cloth “mother” to be a greater reference. He scared the baby monkeys and watched as the monkey ran towards the cloth model. Harlow also conducted experiments where he isolated monkeys from other monkeys in order to show that Those who did not learn to be part of the group at a young age were unable to assimilate and mate when they grew older Harlow’s experiments ceased in 1985 due to APA rules against mistreatment of animals as well as humans.

However, the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health has recently begun similar experiments that involve isolating infant monkeys by exposing them to fearful stimuli. They hope to discover data about human anxiety, but are encountering resistance from animal protection organizations and citizens in general.

5. Learned Helplessness, by Seligman

The ethics of experiments Martin Seligman about learned helplessness would also be questioned today for its mistreatment of animals. In 1965, Seligman and his team used dogs as subjects to test how control might be perceived. The group placed a dog on one side of a box that was divided in two by a low barrier. They would then administer a shock that was avoidable if the dog jumped over the barrier to the other half. The dogs quickly learned how to avoid electrical shocks.

Seligman’s group tied up a group of dogs and administered shocks that they could not avoid. Then, by placing them in the box and shocking them again, The dogs didn’t try to jump over the barrier, they just cried This experiment demonstrates learned helplessness, as well as other experiments framed in social psychology in humans.

4. The Thieves’ Den Experiment, by Sherif

Muzafer Sheriff carried out the thieves’ den experiment in the summer of 1954, carrying out group dynamics in the midst of conflict. A group of pre-teen children were taken to a summer camp, but they did not know that the monitors were actually the researchers. The children were divided into two groups, which were kept separate. The groups only came into contact with each other when they were competing in sporting events or other activities.

The experimenters orchestrated the increase in tension between the two groups, in particular maintaining the conflict. Sherif would create problems such as water shortages, which would require cooperation between the two teams, and required them to work together to achieve a goal. In the end, the groups were no longer separated and the attitude between them was friendly.

Although the psychological experiment seems simple and perhaps harmless, today it would be considered unethical because Sherif used deception, as the boys did not know that they were participating in a psychological experiment. Sherif also did not take into account the informed consent of the participants.

3. The monster study

At the University of Iowa, in 1939, Wendell Johnson and his team hoped to discover the cause of stuttering by trying to turn orphans into stutterers. There were 22 young subjects, 12 of whom were non-stutterers. Half of the group experienced positive teaching, while the other group was treated with negative reinforcement. The teachers continually told the latter group that they were stutterers. No one in either group became a stutterer at the end of the experiment, but those who received negative treatment developed many self-esteem problems that stutterers usually show.

Perhaps Johnson’s interest in this phenomenon has to do with his own stuttering as a child but this study would never pass the evaluation of a review committee.

2. Blue-eyed versus brown-eyed students

Jane Elliott She was not a psychologist, but she developed one of the most controversial exercises in 1968 by dividing students into a blue-eyed group and a brown-eyed group. Elliott was an elementary school teacher in Iowa and was trying to give her students hands-on experience about discrimination the day after Martin Luther King Jr he was murdered. This exercise still has relevance to psychology today and transformed Elliott’s career into one focused on diversity training.

After dividing the class into groups, Elliott would cite that scientific research showed that one group was superior to the other Throughout the day, the group would be treated as such. Elliott realized that it would only take one day for the “higher” group to become more cruel and the “lower” group to become more insecure. The groups then changed so that all students suffered the same harms.

Elliott’s experiment (which he repeated in 1969 and 1970) received much criticism given the negative consequences on the students’ self-esteem, and that is why it could not be carried out again today. The main ethical concerns would be deception and informed consent, although some of the original participants still consider the experiment to be life-changing.

1. The Stanford Prison Experiment

In 1971, Philip Zimbardo, of Stanford University, conducted his famous prison experiment, which aimed to examine group behavior and the importance of roles. Zimbardo and his team chose a group of 24 male university students, who were considered “healthy,” both physically and psychologically. The men had signed up to participate in a “psychological study of prison life,” for which they were paid $15 a day. Half were randomly assigned prisoners, and the other half were assigned prison guards. The experiment took place in the basement of Stanford’s Department of Psychology, where Zimbardo’s team had created a makeshift prison. The experimenters went to great lengths to create a realistic experience for the prisoners, including false arrests in participants’ homes.

The prisoners were given a fairly standard introduction to prison life, rather than an embarrassing uniform. The guards were given vague instructions that they should never be violent towards the prisoners, but they should maintain control. The first day passed without incident, but the prisoners rebelled on the second day by barricading their cells and ignoring the guards. This behavior surprised the guards and supposedly led to the psychological violence that was unleashed in the days following Guards began separating “good” and “bad” prisoners, and doled out punishments that included push-ups, solitary confinement, and public humiliation to unruly prisoners.

Zimbardo explained: “Within a few days, the guards became sadistic and the inmates became depressed and showed signs of acute stress. “Two prisoners abandoned the experiment; one eventually became a psychologist and prison consultant. The experiment, which was originally going to last two weeks, ended prematurely when Zimbardo’s future wife, psychologist Christina Maslach, visited the experiment on the fifth day and told him: “I think it’s terrible what you’re doing to those people.” guys”.

Despite the unethical experiment, Zimbardo is still a working psychologist today. He was even honored by the American Psychological Association with a Gold Medal in 2012 for his lifetime achievement in the science of Psychology.