Cognitive biases (also called cognitive prejudices) are some psychological effects that cause an alteration in information processing captured by our senses, which generates a distortion, erroneous judgment, incoherent or illogical interpretation of the basis of the information we have.

Social biases are those that refer to attribution biases and disturb our interactions with other people in our daily lives.

Cognitive biases: the mind tricks us

The phenomenon of cognitive biases arises as a evolutionary need so that the human being can make immediate judgments that our brain uses to respond quickly to certain stimuli, problems or situations, which due to their complexity would be impossible to process all the information, and therefore requires selective or subjective filtering. It is true that a cognitive bias can lead us to mistakes, but in certain contexts it allows us to decide more quickly or make an intuitive decision when the immediacy of the situation does not allow rational scrutiny.

Cognitive Psychology is responsible for studying these types of effects, as well as other techniques and structures that we use to process information.

Concept of prejudice or cognitive bias

Cognitive bias or prejudice arises from different processes that are not easily distinguishable. These include heuristic processing (mental shortcuts), emotional and moral motivations wave social influence

The concept of cognitive bias first appeared thanks to Daniel Kahneman in 1972, when he realized the impossibility of people reasoning intuitively with very large magnitudes. Kahneman and other academics were demonstrating the existence of patterns of scenarios in which judgments and decisions were not based on what was foreseeable according to rational choice theory. They gave explanatory support to these differences by finding the key to heurism, intuitive processes that tend to be the origin of systematic errors.

Studies on cognitive biases were expanding their dimension and other disciplines also investigated them, such as medicine or political science. In this way the discipline of Behavioral economics which elevated Kahneman after winning the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 for having integrated psychological research into economic science, discovering associations in human judgment and decision making.

However, some critics of Kahneman maintain that heuristics should not lead us to conceive human thought as a puzzle of irrational cognitive prejudices, but rather to understand rationality as an adaptive tool that does not blend into the rules of formal logic. or probabilistic.

Most studied cognitive biases

Retrospective bias or a posteriori bias: It is the propensity to perceive past events as predictable.

Correspondence bias: also called attribution error : It is the tendency to overemphasize the substantiated explanations, behaviors or personal experiences of other people.

Confirmation bias: It is the tendency to find out or interpret information that confirms preconceptions.

Self-service bias: It is the tendency to demand more responsibility for successes than for failures. It is also shown when we tend to interpret ambiguous information as beneficial to our intentions.

False consensus bias: It is the tendency to judge that one’s own opinions, beliefs, values and customs are more widespread among other people than they really are.

Memory bias: Memory bias can disrupt the content of what we remember.

Representation bias: when we assume that something is more probable based on a premise that, in reality, does not predict anything.

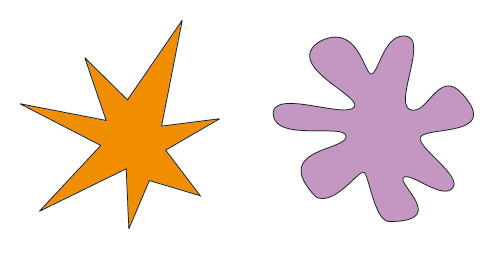

An example of cognitive bias: Bouba or Kiki

He bouba/kiki effect It is one of the most commonly known cognitive biases. It was detected in 1929 by the Estonian psychologist Wolfgang Köhler In an experiment in Tenerife (Spain), the academic showed shapes similar to those in Image 1 to several participants, and detected a great preference among the subjects, who linked the pointed shape with the name “takete”, and the rounded shape with the name “baluba”. . In 2001, V. Ramachandran repeated the experiment using the names “kiki” and “bouba”, and they asked many people which of the forms was called “bouba”, and which “kiki”.

In this study, more than 95% of people chose the round shape as “bouba” and the pointed one as “kiki.” This provided an experimental basis for understanding that the human brain extracts abstract properties from shapes and sounds. In fact, a recent investigation by Daphne Maurer showed that even children under three years old (who are not yet able to read) already report this effect.

Explanations about the Kiki/Bouba effect

Ramachandran and Hubbard interpret the kiki/bouba effect as a demonstration of the implications for the evolution of human language, because it gives clues that the naming of certain objects is not completely arbitrary.

Calling the rounded shape “bouba” could suggest that this bias arises from the way we pronounce the word, with the mouth in a more rounded position to emit the sound, while we use a more tense and angular pronunciation of the “kiki” sound. . It is also worth noting that the sounds of the letter “k” are harder than those of “b”. The presence of this type of “synesthetic maps” suggests that this phenomenon may constitute the neurological basis for the auditory symbolism in which phonemes are mapped and linked to certain objects and events in a non-arbitrary way.

People with autism, however, do not show such a marked preference. While the group of subjects studied scores above 90% in attributing “bouba” to the rounded shape and “kiki” to the angled shape, the percentage drops to 60% in people with autism.