Ethics and morality are constructs that regulate human behavior and allow their direction to what is considered acceptable and positive, both individually (ethically) and collectively (morally). What is good and what is bad, what we should do and what we should not do, and even what aspects we care about and value are elements largely derived from our ethical system.

But sometimes we find ourselves in situations where we don’t know what to do: choosing A or B has, in both cases, negative and positive repercussions at the same time and the different values that govern us come into conflict. We are before situations that pose ethical dilemmas.

A part of moral philosophy

An ethical dilemma is understood to mean any situation in which there is a conflict between the person’s different values and the available options for action. These are situations in which a conflict will arise between various values and beliefs, with there not being a totally good solution and another totally bad option, having both positive and negative repercussions at the same time.

These types of dilemmas require a more or less deep reflection on the alternatives available to us, as well as the value given to the moral values with which we govern ourselves. Often we will have to prioritize one or another value, both entering into conflict in order to make a decision. Likewise, they allow us to see that things are not either black or white, as well as understand people who make decisions other than their own.

The existence of ethical dilemmas that exist in real life or are possible have generated an interesting branch of study focused on our beliefs and values and how these are managed.

They allow us to see how we reflect and what elements we take into account to make a decision. In fact, it is common for ethical dilemmas to be used as a mechanism to educate in the use and management of emotions and values , to raise awareness about some aspects or to generate debate and share points of view between people. They are also used in the workplace, specifically in personnel selection.

Types of ethical dilemmas

The concept of an ethical dilemma may seem clear, but the truth is that there is not only one type. Depending on various criteria we can find different typologies of dilemmas, which can vary in their level of concreteness, in the role of the subject to whom it is presented or in its plausibility. In this sense, some of the main types are the following:

1. Hypothetical dilemma

These are dilemmas that place the person being asked in a position in which you see yourself confronting a situation that is very unlikely to happen in real life. These are not impossible phenomena, but they are something that a person must face in their daily lives on a regular basis. It is not necessary for the person to whom the dilemma is posed to be the protagonist of it, and they can be asked what the character should do.

2. Royal dilemma

In this case, the dilemma raised deals with a topic or situation that is close to the person to whom it is posed, either because it refers to an event that they have experienced or to something that can occur with relative ease in their daily lives. Although they tend to be less dramatic than the previous ones, They can be as distressing or more for this reason. It is not necessary for the person to whom the dilemma is posed to be the protagonist of it, and they can be asked what the character should do.

3. Open or solution dilemma

Dilemmas presented as open or solutions are all those dilemmas in which a situation and the circumstances surrounding it are presented, without the protagonist of the story (who may or may not be the subject to whom it is posed) having yet made any action to solve it. It is intended that the person to whom this dilemma is suggested chooses how to proceed in said situation.

4. Closed or analysis dilemma

This type of dilemma is one in which the situation posed has already been solved in one way or another, having made a decision and carried out a specific series of behaviors. The person to whom the dilemma is posed You should not decide what is done, but rather evaluate the performance of the protagonist.

5. Complete dilemmas

These are all those dilemmas in which the person to whom they are presented is informed of the consequences of each of the options that can be taken.

6. Incomplete dilemmas

In these dilemmas, the consequences of the decisions made by the protagonist are not made explicit, depending largely on the subject’s ability to imagine advantages and disadvantages.

Examples of ethical dilemmas

As we have seen, there are very different ways of proposing different types of ethical dilemmas, with thousands of options and being limited only by one’s own imagination. We’ll see now some examples of ethical dilemmas (some very well known, others less so) in order to see how they work.

1. Heinz Dilemma

One of the best-known ethical dilemmas is the Heinz dilemma. proposed by Kohlberg to analyze the level of moral development of children and adolescents (inferred from the type of response, the reason for the response given, the level of obedience to the rules or the relative importance that following them may have in some cases). This dilemma presents itself as follows:

“Heinz’s wife is sick with cancer, and is expected to die soon if nothing is done to save her. However, there is an experimental drug that doctors believe could save her life: a form of radium that a pharmacist has just discovered. Although this substance is expensive, the pharmacist in question is charging many times more money than it costs him to produce it (it costs him $1,000 and he charges $5,000). Heinz raises all the money he can to buy it, counting on the help and loans of money from everyone he knows, but he only manages to raise $2,500 of the $5,000 that the product costs. Heinz goes to the pharmacist, to whom he tells that his wife is dying and to whom he asks to sell him the medicine at a lower price or to let him pay half of it later. The pharmacist, however, refuses, claiming that he must make money with it since he was the one who discovered it. Having said this, Heinz becomes desperate and considers stealing the medicine.” What should he do?

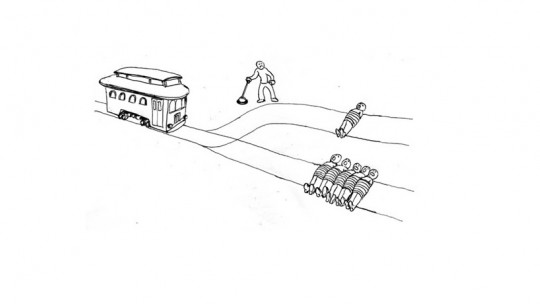

2. Tram Dilemma

The tram or train dilemma is another classic among ethical/moral dilemmas, created by Philippa Foot. In this dilemma the following is proposed:

“A tram/train is traveling out of control and at full speed on a track, shortly before a switch change. Five people are tied to this track, who will die if the train/tram reaches them. You are in front of the switch and you have the possibility of making the vehicle divert to another road, but on which a person is tied. Diverting the tram/train will cause one person to die. If you don’t do it, five will die. What would you do?”

This dilemma also has multiple variants, could greatly complicate the choice. For example, the choice may be that you can stop the tram, but this will cause it to derail with a 50% chance that all its occupants will die (and a 50% chance that everyone will be saved). Or you can look more for the emotional involvement of the subject: propose that in one of the ways there are five or more people who will die if nothing is done and in the other one, but that this one is the partner, child, parent. mother, brother/sister or family member of the subject. Or a child.

3. Prisoner’s Dilemma

The prisoner’s dilemma is one of the dilemmas used by John Nash to explain incentives and the importance of not only one’s own decisions but also those of others to obtain certain results, with cooperation being necessary to achieve the best possible result. Although it is more economic than ethical, it also has implications in this sense.

The prisoner’s dilemma proposes the following situation:

“Two alleged criminals are arrested and locked up, unable to communicate with each other, on suspicion of their involvement in a bank robbery (or a murder, depending on the version). The penalty for the crime is ten years in prison, but there is no palpable evidence of anyone’s involvement in these events. The police offer each of them the possibility of going free if they report the other. If both confess to the crime, they will each serve six years in prison. If one denies it and the other provides evidence of his involvement, the informant will be released and the other will be sentenced to ten years in prison. If both deny the facts, both will remain in prison for one year.”

In this case, more than moral we would be talking about the consequences of each act for oneself and for the other and how the result depends not only on our actions but also on those of others.

4. The noble thief

This dilemma poses the following:

“We witness how a man robs a bank. However, we observe that the thief does not keep the money, but rather gives it to an orphanage that lacks the resources to support the orphans who live there. We can report the theft, but if we do it is likely that the money that the orphanage can now use to feed and care for the children will have to be repaid.”

On the one hand, the subject has committed a crime, but on the other hand he has done it for a good cause. To do? The dilemma can be complicated if we add, for example, that a person died during the bank robbery.

5. The exam

Sometimes the right decision comes in a very ambiguous situation where we don’t know if we have committed a violation or not. This ethical dilemma is based on these types of situations. This scenario presents us:

“You are in a university classroom taking an exam: all the students are sitting in desk chairs lined up, answering questions that must be answered in writing. At a certain moment, you have spent several minutes trying to solve a question that resists you, and seeing You are not short of time, you decide to rest for a couple of minutes, to see if by disconnecting you can better evoke the memories. However, after spending a while with your mind blank and without thinking about anything in particular and with a lost gaze, You realize that you just saw the correct answer on the answer sheet of the person in front of you. Given that you most likely would not be able to remember the correct answer, do you answer the question, or leave it alone. in white?”.

It’s a simple exam question, but… Should you take responsibility for having “copied”, even if it is not entirely voluntary? Or on the other hand, is it not your fault that your gaze was directed at the other person’s exam sheet?

Sometimes we also have to face them in real life

Some of the ethical dilemmas proposed above are statements that may seem false or a hypothetical elaboration that we will never have to face in real life. But the truth is that on a day-to-day basis we can reach having to face difficult decisions with negative consequences or implications, whatever decision we make.

For example, we may find that an acquaintance performs some unethical act. We can also observe a case of bullying, or a fight, in which we can intervene in different ways. We frequently encounter homeless people, and we may be faced with the dilemma of whether to help them or not. Also on a professional level : a judge, for example, must decide whether or not to send someone to prison, a doctor may be faced with the decision of whether or not to artificially prolong someone’s life or who should or should not undergo surgery.

We can observe professional malpractice. And we can also face them even in our personal lives: we can, for example, witness infidelities and betrayals towards loved ones or carried out by them, having the conflict of whether to tell them or not.

In conclusion, ethical dilemmas are an element of great interest that tests our convictions and beliefs and force us to reflect on what motivates us and how we organize and participate in our world. And it is not something abstract and foreign to us, but rather it can be part of our daily lives.