Nowadays, the study of the brain is very advanced (although not as advanced as we would like, since the human brain still hides many questions). Indeed, during the last 20 years more progress has been made in the study of the brain than in all the previous millennia.

The history of the study of the brain is fascinating How has this organ been considered by different times and cultures? From Prehistory to the present day, passing through Ancient Egypt and the European Middle Ages, the brain has gone through different states of appreciation.

History of research on the human brain

In this article we offer you a brief journey through the study of the human brain.

The brain in Prehistory: the beginning of trepanation

The brain and skull area were already important to men and women in the first millennia. The oldest manifestations of cranial surgery date back to no less than the 6th millennium BC.

Numerous human remains have been found with obvious signs of trepanation ; Famous is the case of the 12 graves found in Rostov-on-Don, Russia, where at least 3 people showed holes in their skulls that had evidently been made with sharp instruments. But the practice was very common in other regions of the world that, in theory, were not culturally connected: we also find cases in Africa and South America, where pre-Inca civilizations (3rd millennium BC) practiced trepanation to alleviate migraine or epilepsy and, In addition, they used coca or other vegetables to mitigate the pain.

This raised the question: Were the trepanations part of a ritual, or were they performed for medical reasons? The first case would mean that, during Prehistory, the brain enjoyed capital importance in the religion of these first human communities. In any case, and despite the low survival rate, there have been cases in which the patient survived at least 4 years after the operation.

In Egypt, the brain is not important

Ancient Egyptian funerary rituals are rich and elaborate. First, the organs of the deceased were extracted and placed in the so-called canopic jars. The body was then dried with natron. The mummy was buried, after various rituals, with its canopic jars, since the organs had an important postmortem function.

But was the brain also kept? The answer is no. Those responsible for mummification extracted the brain from the corpse through the nostrils , using an iron hook, and then the organ was thrown into the trash. This means, of course, that Egyptian religion did not attach any importance to the brain, nor did it assume any important function in the afterlife.

However, despite not granting it any spiritual value, there is evidence that the ancient Egyptians knew about brain morphology and its relationship with certain injuries or diseases. Thus, in the call Edwin Smith papyrus (2nd millennium BC) , we find a detailed analysis that highlights, for the first time, the importance of the central nervous system, as well as the brain as the ruler of the body’s functions. The document is of capital importance, since it constitutes the first medical testimony based on empirical and objective observation.

In fact, it is believed that, in Ancient Egypt, trepanations were performed to treat migraines, epilepsy and other ailments. And, again as during Prehistory, many of the patients survived. It may even be that, in some cases, their pain was relieved, since trephination could be relatively effective in relieving pressure on the brain or draining bruises.

The classical era and the bases of the study of the brain in the West

All Western medicine, until very recent times, was based on the principles of the Greek doctor Hippocrates (who, in turn, is very likely to have drawn on Egyptian knowledge). Knowledge was concentrated in Alexandria after the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great ; The city library, famous throughout the world, housed many books related to medicine and human anatomy.

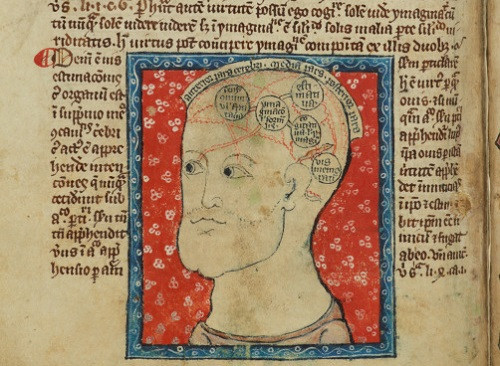

In fact, it was Herophilus of Chalcedon who established one of the currents that would later prevail in the Middle Ages. This Greek wise man described the configuration of the cerebral cortex and its ventricles, in which he stated that the higher functions were located. Gregor Reich picks up this theory many centuries later, in his work Margarita Philosophica.

Galen was another of the great names of classical medicine. His works contain many errors (it is believed that, due to the prohibition on dissecting human corpses, the doctor had to content himself with animals). However, he established what would be another of the currents that would continue in force in medieval times: placed the mind and, therefore, reasoning, in the brain tissue

The Middle Ages, the brain and the “stone of madness”

Heir to classical wisdom, the medieval era includes, as we have already indicated, the main theories of Herophilus and Galen. In the Middle Ages it was believed that higher functions (reasoning, emotions…) were found in the ventricles of the brain. Thus, insanity or dementia is seen as the manifestation of a problem in these areas of the brain.

For the medieval human being, madness is caused by the formation of mineral layers that press on the brain or plug the ventricles For this reason, it is quite common to find in this era supposed “doctors” who offered to trepan “madmen” (a rather ambiguous term in the Middle Ages) and thus extract the “stone of madness.” Famous is the painting by Hieronymus Bosch, preserved in the Prado Museum, where the artist makes a caricature of such an activity: a charlatan is extracting the stone from the head of a man, who allows himself to be deceived by the trickster’s evil tricks. In Hieronymus Bosch’s painting, a tulip appears instead of the stone, a clear reference to the deception of which the man is being a victim, as well as to his own foolishness.

During the Middle Ages, madness was faced in contradictory ways. The “madman” can be an enlightened person, a being who sees things that others do not see (and that is why tributes are dedicated to him such as the Festival of Fools, a true exaltation of madness) or he can be a demon-possessed person to whom there is to expel from the community.

In any case, The only solution is exorcism or removal of the stone causing the dementia

Dissection prohibited

The Middle Ages was not the only time in which the dissection of corpses for anatomical study was prohibited. Already during Greek and Roman times there were prejudices in this regard; We have already commented how Galen had to experiment with animal corpses to draw conclusions from them.

Towards the 13th century, dissections of human bodies began to become more frequent, although the scarcity of corpses fueled the assault on tombs, so the authorities decided to impose restrictions again. Already in the 15th century we find a more or less common activity in terms of dissecting corpses: Leonardo da Vinci himself practiced dissections to study human anatomy.

This advance in direct exploration of the human body allowed the study of the brain to speed up and the first neurological studies began to proliferate.

The scientific revolution

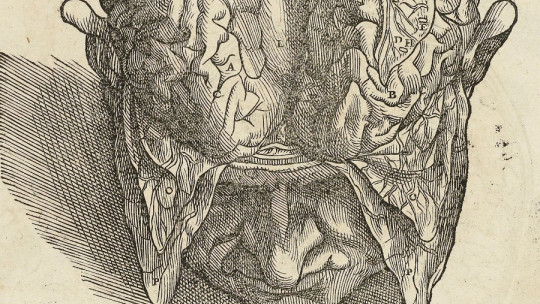

In the 16th century, Andrés Vesalius published his De humani corpus fabrica , a capital work that represents a turning point in the study of human anatomy and, therefore, the brain. This extensive work (no less than 10 volumes) laid the foundations of modern brain anatomy.

Based on his lectures at the University of Padua, this compilation by Vesalius draws on cadaver dissections to present a detailed examination of various organs. Advances in printing made it possible to accompany the books with high-quality engravings that were a perfect illustration for the explanations. This work emphasizes that the ventricles of the brain are the place where functions such as memory or emotions are based.

A little later, Nicolás Steno, a Danish doctor, stated that the brain is the most delicate part of the human body and that, therefore, it must be cared for to avoid any dysfunction that culminates in madness. For his part, Thomas Willis uses the term neurology for the first time, combining the Greek word neuro (string) with logos. Willis is considered the father of modern neurology; In his work Cerebri Anatome, this English doctor makes a very precise description of the internal morphology of the brain.

Already in the 18th century, Giambattista Morgagni relates diseases to anatomical lesions for the first time ; For example, he claimed that stroke was caused by lesions in the veins of the brain. Morgagni is the author of the first book on pathological anatomy.

The 19th century, a time of progress?

The 19th century will mean an important advance in the study of the brain. Santiago Ramon y Cajal presented his work on the nervous system, where he stated that it is composed of independent cells connected to each other in specific places (neurons). His work earned him the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1906 and laid the foundations for current neuroscience.

However, the supposed century of progress also had its dark points. Darwin’s theory of evolution gave rise to the emergence of racist theories that tried to “justify” the inferiority of races In other words, the absurd theory spread that there were human groups more evolved than others. This idea reached its zenith in the 20th century, when the Nazi party attempted to “prove” the supremacy of the Aryan race by measuring skulls, and other even more macabre experiments.

The study of the brain continues its course We are getting closer to understanding this fascinating organ in its entirety, but there are still many doors to open.