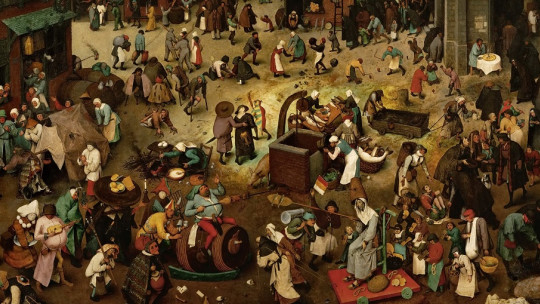

We all have in mind the famous table of Hyeronimus Bosch (better known as Hieronymus Bosch), in which surgery is being performed to remove the so-called “madness stone.” Indeed, in the Middle Ages one of the beliefs that revolved around “madness” was that it was due to an excessive proliferation of mineral structures in the brain that, consequently, had to be removed. Some did not agree with this theory, among whom we must count Hieronymus Bosch; In fact, in this painting the painter makes a scathing criticism of this activity, which he considered the preserve of charlatans and liars.

So, How were mental problems treated in the Middle Ages? What is myth and truth in what we know? Is it true that the mentally ill were considered “demon-possessed,” possessed by an evil spirit?

Let’s go in parts, because, as always happens with the topics that have given rise to so many legends, neither everything is true nor everything is false. Let’s see it below.

Mental disorders in the Middle Ages: “holy” or “mad”?

It is necessary to point out that, obviously, The term “mental disorder” did not exist in medieval times. To refer to people who behaved strangely or differently and who showed symptoms of “mania”, the word “crazy” was invariably used. In the Italian context, the word was used Pazzo and, in French-speaking areas, fou. The illness they suffered was, simply, “madness” or, as it was called in French lands, the folie.

In the Middle Ages, a contradictory era if ever there was one, “madness” could be seen in many ways, some absolutely opposite to each other. Because the “madman” could be both the poor “dangerous degenerate”, whose behavior was often attributed to demonic possession, and the “enlightened one”, the one who knew the highest truths, directly inspired by God.

In the first group of “crazy people” we find an endless number of disorders ranging from epilepsy (the most common cause for calling someone “possessed”) to “manias”, a very generic word that at the time was used to designate a a multitude of varied symptoms, and which currently, through the writings that have been left to us, have been able to be identified with clear signs of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, among others.

On the other hand, the second group included people who, due to their extreme holiness or exemplary Christian conduct, They immediately crossed the border of the insane and entered the realm of the “enlightened.” ; people whose strange attitude was justified by their desire for spiritual transcendence, in what in the Middle Ages was called Imitatio Christi (imitation of the life of Christ). These “enlightened ones” could be hermits, saints who practiced the Holy Fast (we will talk about it later), or who experienced mystical visions, as is the case of the famous Hildegard of Bingen.

Belonging to one group or another did not, in reality, obey any rules. Or very few, and quite arbitrary. Because, Often, not even “mystical visions” could save you from being considered “mad,” or even worse, “heretic.”. Manifesting strange behaviors, then, could be a ticket to veneration or degradation and death.

Mystical visions?

We can take two famous cases as an example: the aforementioned Hildegard of Bingen, a 12th century German nun, confessed to having had countless mystical visions; visions that the pope knew and that he encouraged, considering them “the fruit of the Holy Spirit.” On the other hand, we have Joan of Arc, tried and condemned as a heretic precisely for also suffering sacred visions… In this last case we have clear (and indisputable) political motives.

In any case, it is interesting to take these “sacred visions” into account in our small article, since, according to many experts, Hildegard’s famous visions could have been due to certain mental or, at the very least, emotional disorders.

Thus, according to the historian Charles Singer (1876-1960), The nun could have suffered some type of severe migraine that would have caused imbalances in her perceptions. This theory was later supported by the neurologist Oliver Sacks (1933-2015), and seems to explain, therefore, the beams of “light and fire” that the mystic confesses to seeing in her visions.

The authors who refute this theory base their opinion on the fact that analyzing Hildegard’s visions only from a clinical perspective is not taking into account the context in which the saint lived and wrote her work. Hildegard imbues her visions with an ancient tradition in order to legitimize her work, a tradition already found in the prophets Daniel and Ezekiel and, above all, in the Apocalypse de San Juan. Thus, the saint would be using a series of allegories known in the Middle Ages to express the divine message, and they would not actually imply a real vision.

Joan of Arc has also been the subject of studies from a psychiatric perspective ; The possibility of schizophrenia has been considered as the origin of his mystical visions and auditions; Furthermore, the symptoms of schizophrenia usually appear in adolescence, and let us remember that Juana began to “hear voices” when she was 13 years old. Other authors refute this theory, since the saint did not present progressive destructuring of the personality, which does occur in schizophrenics.

Possessions and exorcisms

The “madman” can also be considered in the Middle Ages as a victim of the evil of a demon that had entered into it. This was the explanation for the somewhat erratic behavior of these people, who presented, judging by the analysis of the texts, obvious symptoms of anxiety and personality disorders.

There has been much speculation about the disorder that was hidden behind the supposed “demonic possession”; Most authors point to epilepsy, whose symptoms are impressive enough to confirm the presence of a “demon”: rolling eyes, convulsions, foaming at the mouth… In these situations, the “solution” used to be exorcism. , a practice that sought to expel the demon from the body of the affected person.

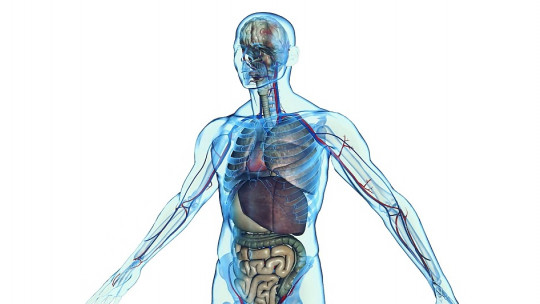

In any case, it must be kept in mind that In the Middle Ages, in addition to the religious perception of mental disorder, a scientific perception coexisted, inherited from the Hippocratic tradition and Galen’s medicine. Saint Thomas Aquinas himself refers to Galen’s theories when he talks about illness in his work, which makes it evident that in the Middle Ages health problems were not always examined from a religious prism.

The theory of humors, endorsed by the Roman Galen (129-216), tried to explain illness, both physical and psychological, through an imbalance in the humors of the human body. For example, “melancholy” (the term used at the time to refer to depression) was formed when there was an excess of black bile in the body.

Analogies with modern mental disorders

Fernando Espí Forcén (University of Murcia), in his Doctoral Thesis on mental health in the Late Middle Ages (see bibliography), proposes interesting theories about the analogies between certain medieval behaviors and some disorders diagnosed today.

For example, consider the case of the “holy women” who practiced what is known as the “holy fast”. The practice consisted of persistent fasting, combined with induction of vomiting when eating food, which, quite often, caused amenorrhea (absence of menstruation). Espí Forcén establishes a parallel between the attitude of these women and anorexia nervosa; What’s more, psychologically, we would be facing the same problem, since both the “holy women” of the Middle Ages and the women of today want to achieve the “ideal” of their time: holiness in the former, “beautiful” thinness ” in the latter. The goal is, therefore, the same; satisfy society and feel accepted.

In his same work, Espí Forcén also carries out an interesting study on the Ars moriendi (literally, “the art of dying”), the medieval treatise that advised friars to help the terminally ill die peacefully. Through a careful analysis of the various parts of the treatise, Espí Forcén establishes a clear parallel between the religious methods used for the dying to find calm when dying with those used in current acceptance therapy. Furthermore, the emotional and psychological states of the dying, as described in the Ars moriendiare similar to those noted by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1926-2004), an expert in care of the terminally ill.

For example, in the Ars moriendi Medieval times there are remedies for the sick to fight against the despair that comes upon knowing that they must die; Likewise, methods are also offered to control the impatience of the dying person, expressed in mood disturbances, confusion and uncontrollable movements. In this sense, the author of the study states that it would be techniques closely related to current death acceptance therapy.

The first “innocent hospitals”

At this point, we can ask ourselves what the treatment of mentally ill people was in the Middle Ages. Much myth and legend has also come down to us from this. Because, although it is true that the mentally ill caused a certain rejection in society and, often, also fear, it is no less true that The Church used to consider these “crazy people” innocent of their torture so they used to be treated with Christian charity.

In this sense, it is necessary to talk about the first hospitals specially founded to house and care for these mentally ill patients, which received the generic name of “innocent hospitals” for the reasons given above. The first hospital dedicated exclusively to these patients was the Hospital de Ignoscents, Folls e Orats, founded in 1409 in Valencia by Fray Juan Gilbert Jofré, of the Order of Mercy. The hospital has the honor of being the first “psychiatric” hospital in the history of Europe.

In the Ignocents Hospital, the sick found a safe place to live, since otherwise they were condemned to wandering and, very often, to beatings by passers-by. Already in the Middle Ages it was known that leisure did not help these people improve, so in the Valencia hospital tasks were assigned to the sick: cultivating the garden, doing craft work, embroidering, cooking… Work kept them busy, made them feel useful, and many of them improved their mental condition.

This work philosophy, which includes the precepts of the Benedictine order of Pray and work (pray and work) spread to the other hospitals for the mentally ill, which immediately began to be founded. In 1425, what would become one of the most important and recognized hospitals was founded: the Hospital of Our Lady of Grace of Zaragoza, whose motto Domus Infirmorum Urbis et Orbis (“House for the Sick of the Whole World”) gives an idea of its international character.