Signal theory, or signaling theory brings together a set of studies from the field of evolutionary biology, and suggests that the study of the signals exchanged in the communication process between individuals of any species can account for their evolutionary patterns, and can also help us differentiate when The signals emitted are honest or dishonest.

In this article we will see what signaling theory is, what honest and dishonest signals are in the context of evolutionary biology, as well as some of its consequences in studies on human behavior.

Signaling theory: is deception evolutionary?

Studied in the context of biological and evolutionary theory, deception or lying can acquire an adaptive meaning. Transferred from there to the study of animal communication, deception is understood as strongly linked to persuasive activity, since it consists mainly of providing false information for the benefit of the sender, even if it means harm to the sender (Redondo, 1994).

The above It has been studied by biology in different species of animals, including humans through the signals that some individuals send to others and the effects that these produce.

In this sense, evolutionary theory tells us that the interaction between individuals of the same species (as well as between individuals of different species) is crossed by the constant exchange of different signals. Especially when it comes to an interaction that involves some conflict of interest, the signals exchanged may seem honest, even if they are not.

In this same sense, the theory of signals has proposed that the evolution of an individual of any species is marked in an important way by the need to emit and receive signals in an increasingly perfected way, so that this allows you to resist manipulation by other individuals.

Honest Signals and Dishonest Signals: Differences and Effects

For this theory, the exchange of signals, both honest and dishonest, has an evolutionary character, since by emitting a certain signal, the behavior of the receiver is modified, for the benefit of the one who issues it.

These are honest signals when the behavior corresponds to the apparent intention. On the other hand, these are dishonest signals when the behavior appears to have one intention, but in reality has another, which is also potentially harmful to the person who receives it and surely beneficial for whoever issues it.

The development, evolution and fate of the latter, dishonest signals, can have two possible consequences for the dynamics of some species, according to Redondo (1994). Let’s see them below.

1. The dishonest signal is extinguished

According to signaling theory, deception signals are especially emitted by those individuals who have an advantage over others. In fact, it suggests that in an animal population where there are predominantly honest signals, and one of the most biologically efficient individuals initiates an honest signal, the latter will expand rapidly.

But what happens when the receiver has already developed the ability to detect dishonest signals? In evolutionary terms, individuals who receive dishonest signals generated increasingly complex evaluation techniques, in order to detect which signal is honest and which is not, which gradually decreases the profit of the sender of the deception and finally causes its extinction.

From the above it can also happen that dishonest signals are eventually replaced by honest signals. At least temporarily, while the likelihood of them being used with dishonest intentions increases. An example of this is the threat displays carried out by seagulls. Although there is a wide variety of such displays, they all seem to serve the same function, meaning that a set of potentially dishonest signals have been fixed as honest signals.

2. The dishonest signal is fixed

However, another effect may occur in the presence and increase of dishonest signals. This is for the signal to become permanently fixed in the population, which happens if all honest signals are extinguished. In this case, the dishonest signal no longer remains a dishonest signal, since in the absence of sincerity the deception loses meaning. It remains, therefore, as a convention that loses connection with the initial reaction of the recipient.

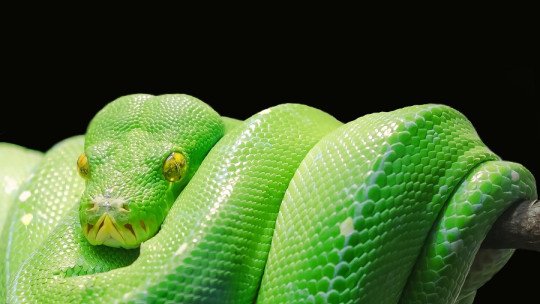

An example of the latter is the following: a flock shares an alarm signal that warns of the presence of a predator. This is a sincere signal, which serves to protect the species.

However, if any of the members emit that same signal, but not when a predator approaches, but when they experience failure in the competition for food with other members of the same species, this will give them an advantage over their flock and would make that the signal (now deceptive) is transformed and maintained. In fact, several species of birds make false alarm signals to distract others and thus obtain food.

The handicap principle

In 1975, the Israeli biologist Amotz Zahavi proposed that the emission of some honest signals involves such a high cost that only the most biologically dominant individuals can afford to do them.

In this sense, the existence of some honest signals would be guaranteed by the cost they entail, and the existence of dishonest signals as well. This ultimately represents a disadvantage for less dominant individuals who want to emit false signals.

In other words, the benefit acquired by the emission of dishonest signals would be reserved only for the most biologically dominant individuals. This principle is known as the handicap principle (which in English can be translated as “disadvantage”).

Application in the study of human behavior

Among other things, signal theory has been used to explain some interaction patterns as well as the attitudes displayed during coexistence between different people.

For example, attempts have been made to understand, evaluate and even predict the authenticity of different intentions, objectives and values generated in interactions between certain groups.

The latter, according to Pentland (2008), occurs from the study of their signaling patterns, which would represent a second communication channel. Although this remains implicit, it allows us to explain why decisions or attitudes are made within the most basic interactions, such as in a job interview or in a first coexistence between unknown people.

In other words, it has served to develop hypotheses about how we can know when someone is genuinely interested or attentive during a communicative process.