It will not seem strange to us to hear that we suffer from “post-vacation syndrome” if we feel emotionally down when we return from a trip and we abruptly reconnect with our routine or, on the contrary, that we suffer from “free time syndrome” if we go on vacation and find it difficult relax because we are used to leading a very hectic pace of life.

These labels, despite being used normally and seeming harmless, are a reflection of how our society has become intolerant of discomfort, pain and uncertainty.

This has led us to pathologize states of mind, feelings and emotions that are inherent to the human condition such as sadness, anger, stress, problems in adolescence or loneliness, among others, and that could be more related to “ feeling bad” than with “suffering from an illness” (Pérez, Bobo and Arias, 2013).

The health paradox

To the above is added what we call “health paradox” that is, what in the most developed countries occurs when the definition of health is very objective and feeds back to the growth of the problems declared in medical consultation.

This happens, for example, when the description of symptoms to identify a disease or disorder is very specific and involves a series of “symptoms” that can also appear in difficult or conflictive situations.

Thus, it is common to hear someone say that they have “depression” without saying that they are “sad,” or that they have “anxiety” without saying that they are nervous. Likewise, the more resources in the health system expand, the more people say they are sick.

Therefore, this mechanism that feeds back the perception of illnesses in the face of normal reactions during daily adversities is based on assuming that there are no healthy people, but only undiagnosed sick people (Orueta et al., 2011), given that somehow, at some point or another, we would all fit into some diagnostic category.

What do we understand by health and happiness?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health no longer as the absence of disease, but as the achievement of absolute well-being, which in some way ensures the establishment of this extreme pathologization of discomfort, in addition to a search for immediate happiness. and excessive consumption of sedative drugs that prevent us from having to endure small doses of suffering.

This is due to unattainable place where the foundations of the health standard for human beings are laid whose natural condition is variability in mood and causes anything that is not perceived as “absolute well-being” to be considered “pathological.”

However, the problem is not whether or not to seek happiness, it is that we have already been taught where we should find it, and we, without questioning anything at all, have believed it. Consumption, advances in technology and science and individualism are those three great paths that according to our society we must follow to find happiness (Lipovetsky and Charles, 2006). All three are part of the material and are intertwined with each other, being at the same time, small portions of intermittent happiness and unhappiness.

On the one hand, they offer us moments of comfort and pleasure, and on the other, they make us feel restlessness and restlessness. For example, these allow us to access remedies for pain, privileged purchases or useful technological advances, but at the same time they make us want more and more and feel that it is never enough, thus generating feelings of dissatisfaction and unhappiness.

Therefore, buying in the absence of necessity as a method of evasion, lacking a critical approach to medical science and becoming more individualistic, demanding and sensitive to frustration, It has turned us into consumers who are sometimes happy, but always dissatisfied.

An excess of medicalization

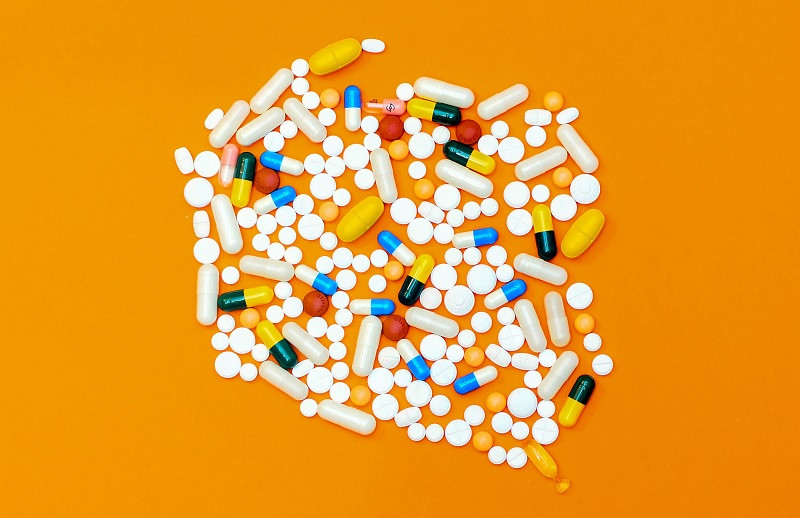

The field of mental health is a good example of everything discussed above. In this area, despite recent efforts to reverse this situation, a biological perspective has been and is being abused for the treatment of human “discomfort.”

This leads to excessive medicalization as a means to combat “problems” which are actually part of the normal fluctuations of life, providing immediate, although fleeting, well-being. In this way, we lose autonomy, getting used to taking a passive attitude towards problems.

Thus, perceiving pain, restlessness or anxiety as illnesses allows us to label them and, consequently, have a treatment available, that is, a solution that is found externally and that, therefore, does not directly involve us. . As Conrad said in 2007, this is a way to transform human conditions into treatable diseases which in this case feeds back to the fact that science and money go hand in hand and, therefore, this discipline ends up being a company with economic purposes (Smith, 2005).

Nowadays, as a general rule, the treatment sought before “the disease” arrives is usually reduced to drugs, and these act more as a “floater” than as a “rescue boat” when in reality what we need is to become familiar with the cold water and learn to swim. After all, Alleviating the consequences of a problem makes it more bearable and bearable, but it does not make it disappear. but it helps to momentarily forget that said problem exists.

For example, it will be much easier to think that a child is unruly and disobedient because he has Attention Deficit Disorder (ADHD) than to think that said behavioral agitation is due to a dysfunctional family dynamic (Talarn, Rigat & Carbonell, 2011). Then, the solution to a symptom perhaps given more by a family problem than by a disorder, will be found in an amphetamine drug and not in questioning the beliefs that to this day have guided their behavior as parents.

New therapeutic perspectives

Definitely, As a society we should understand uncertainty and suffering as part of life in order to normalize problematic situations that have already been medicalized (Perez et al, 2013), and that, in addition, could derive from the interaction between the individual and their context and history (Bianco and Figueroa, 2008). Now, this becomes complicated as long as any lament continues to be interpreted from a medical perspective, as this is economically beneficial and not scientific (Talarn et al., 2011).

Even so, it is true that this problem is beginning to become visible and Therapies such as “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy” (ACT) are beginning to be known. , whose main premise is to normalize discomfort, understanding it as a product of the human condition. This exposes how society teaches us to resist suffering that is normal, and how this resistance can generate true pathological suffering.

Its objective, then, is to get rid of the avoidant and destructive pattern generated by “the culture of feeling good” that leads us to avoid pain that is part of our life cycle and helps us grow (Soriano and Salas, 2006).

In my opinion, it is urgent to make this type of therapy visible, since it is difficult for us to open our eyes if it is still beneficial to make us believe that the solution is to close them. So we should support the growth of this new philosophy, because As long as we continue to be taught to be treatable patients, we will continue to be prepared to consume and not to take an active attitude in the face of conflictive situations in life (Lobo, 2006).