Picture a movement that doesn’t ask for equal pay or voting rights—it demands the complete dismantling of every institution that puts men in power over women. Not reform. Not incremental change. Total revolutionary transformation of society from its foundations. This is radical feminism, and it emerged in the late 1960s arguing that all other feminist approaches were treating symptoms while ignoring the disease: patriarchy itself, the systematic domination of women by men as the oldest and most fundamental form of human oppression.

The word “radical” comes from the Latin “radix,” meaning root. Radical feminists go after the root cause of women’s subordination, which they identify as male dominance embedded in every social structure—family, marriage, sexuality, reproduction, law, religion, culture. Where liberal feminists sought equality within existing systems and socialist feminists blamed capitalism, radical feminists insisted the problem runs deeper: men as a class benefit from controlling women as a class, and no amount of legal reform will change this fundamental power dynamic.

This perspective generated enormous controversy from its inception. Radical feminists argued that marriage is legalized prostitution, that the nuclear family is a prison for women, that heterosexuality itself might be a tool of patriarchal control, and that motherhood as socially constructed serves male interests rather than women’s wellbeing. These weren’t polite requests for inclusion—they were accusations that the entire social order is designed to subordinate women.

The movement produced some of feminism’s most influential and most contested ideas. The slogan “the personal is political” transformed how people understood private life, revealing that supposedly intimate choices about sex, marriage, and family are actually political expressions of systemic power. Consciousness-raising groups gave women spaces to recognize that their individual struggles reflected collective oppression. Campaigns against rape, domestic violence, and pornography reframed these as political issues rather than private matters.

But radical feminism has also been criticized—from within feminism and beyond—for essentialism (treating all women and all men as monolithic groups), for ignoring race and class differences among women, for seeming to position men as enemies rather than potential allies, and for proposing solutions like separatism that many find impractical or undesirable. Contemporary debates about sex work, transgender rights, and reproductive technology have created new divisions within and about radical feminism.

Understanding radical feminism matters not just historically but for making sense of current feminist debates. Many contemporary positions—on topics from surrogacy to pornography to what defines a woman—trace back to radical feminist arguments from the 1970s. This article explores what radical feminism is, where it came from, what principles define it, its famous phrases and slogans, examples of radical feminist activism, and why it remains both influential and controversial decades after its emergence.

Origins: The Second Wave’s Revolutionary Wing

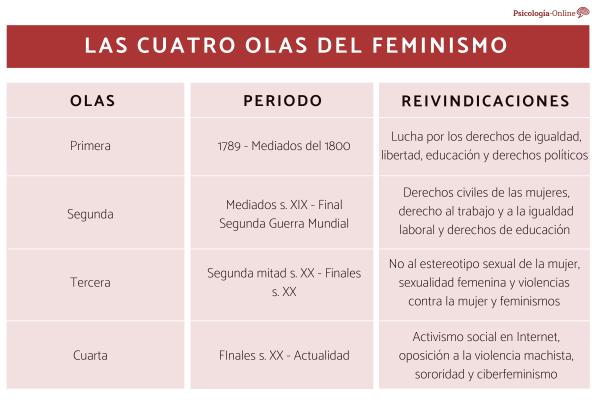

Radical feminism emerged around 1967-1968 as a faction within the broader second-wave feminist movement, which itself had gained momentum throughout the 1960s. While liberal feminists like Betty Friedan and the National Organization for Women (NOW) focused on legal equality and access to male-dominated institutions, a younger generation of feminists who’d cut their teeth in civil rights and anti-war movements found this approach insufficient.

These women had experienced sexism within supposedly progressive movements—being relegated to clerical roles while men led, having their concerns dismissed, facing sexual exploitation justified by rhetoric about free love. When they tried addressing these issues, male leftists told them to wait until after the revolution, that women’s liberation was secondary to class struggle or racial justice. This radicalized many young feminists, leading them to conclude that male dominance transcended political ideology and required its own revolutionary movement.

Key early groups included New York Radical Women (founded 1967), Redstockings (1969), The Feminists (1968), and WITCH (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell, 1968). These collectives rejected hierarchical organization, practiced consciousness-raising, and staged dramatic protests highlighting women’s oppression. The Miss America protest in 1968—where feminists crowned a sheep and threw bras, girdles, and makeup into a “freedom trash can”—became iconic, though they never actually burned bras despite that myth persisting.

Intellectual foundations came from several sources. Simone de Beauvoir’s “The Second Sex” (1949) had argued that women are made, not born—that femininity is socially constructed to serve male interests. Kate Millett’s “Sexual Politics” (1970) analyzed how literature reinforced patriarchal ideology. Shulamith Firestone’s “The Dialectic of Sex” (1970) applied Marxist analysis to sex class, arguing that women’s reproductive biology made them vulnerable to male dominance.

Ti-Grace Atkinson’s 1969 essay “Radical Feminism” provided theoretical grounding, arguing that the original class division was between men and women, predating and underlying all other forms of oppression. She wrote that men’s need for power drove them to oppress women, and that this became the template for all subsequent hierarchies. This positioned sex-based oppression as foundational, making women’s liberation not just one goal among many but the prerequisite for all human liberation.

Core Principles: Patriarchy as Root Cause

Radical feminism rests on several interconnected principles that distinguish it from other feminist perspectives. Understanding these core tenets is essential for grasping both its analytical power and its controversies.

The central concept is patriarchy—not just individual sexist men but a comprehensive system of male dominance that pervades all social institutions and relationships. Patriarchy predates capitalism, exists across all cultures, and structures everything from intimate partnerships to global politics. Men as a class benefit from women’s subordination, regardless of whether individual men are conscious of or supportive of feminist goals. This doesn’t mean all men are equally powerful or that all women are equally oppressed, but that the fundamental organizing principle of society positions men as dominators and women as subordinated.

Sex class analysis treats women and men as political classes analogous to economic classes in Marxism. Just as workers and capitalists have fundamentally opposed interests, women and men have opposed interests under patriarchy. Women’s liberation requires recognizing this class conflict rather than pretending men and women naturally have shared interests. This framing was controversial even within feminism—many women didn’t want to view their fathers, brothers, husbands, or sons as class enemies.

“The personal is political” became radical feminism’s most famous slogan, expressing the insight that supposedly private experiences are actually political. A woman’s difficulty achieving orgasm isn’t personal inadequacy but reflects how female sexuality has been constructed to serve male pleasure. Domestic violence isn’t a private family matter but systematic enforcement of male dominance. The division of household labor isn’t individual couples’ arrangements but the political institution of unpaid women’s work. This principle justified analyzing and politicizing aspects of life previously considered too intimate for political discourse.

Consciousness-raising emerged as radical feminism’s distinctive practice. Small groups of women would meet regularly, sharing personal experiences around specific topics—work, family, sexuality, body image. Through comparing stories, women recognized that experiences they’d thought were individual failures or unique problems actually reflected shared patterns of oppression. This collective analysis built feminist consciousness and political solidarity while validating women’s subjective experiences as sources of knowledge about patriarchy. Consciousness-raising groups proliferated across North America and Europe, becoming the primary means through which women encountered radical feminist ideas.

Marriage, Family, and Heterosexuality Under Critique

Radical feminists subjected traditional institutions of marriage and family to withering analysis, arguing these weren’t natural arrangements but political structures enforcing women’s subordination. This critique was shocking to mainstream society in the 1970s and remains controversial today.

Marriage, from a radical feminist perspective, is a contract through which women become men’s property—historically quite literally, with wives’ legal existence subsumed under their husbands’. Even modern marriage perpetuates inequality through women performing unpaid domestic labor, taking responsibility for emotional caretaking, and often sacrificing careers for family. The wedding ceremony itself—fathers “giving away” daughters, brides taking husbands’ names, the symbolism of the white dress signifying virginity—encodes patriarchal ownership. Some radical feminists argued marriage should be abolished; others said it could only be acceptable if completely reimagined without its patriarchal heritage.

The nuclear family came under similar scrutiny. Rather than a natural unit based on love, radical feminists analyzed the family as an institution serving patriarchy by privatizing women’s labor, isolating women in individual households, and reproducing gender through childhood socialization. Mothers raise daughters to be submissive and sons to be dominant, perpetuating patriarchy across generations. The ideology of motherhood as women’s highest calling traps women in unpaid reproductive labor while men are free for public achievement.

Heterosexuality itself became subject to radical feminist analysis. Was heterosexual desire natural or socially constructed? If women are subordinated under patriarchy, can heterosexual relationships ever be equal, or do they inherently involve collaboration with one’s oppressor? Adrienne Rich’s influential 1980 essay “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence” argued that heterosexuality is enforced through various mechanisms that make it seem natural and inevitable, while actually serving to maintain male access to women sexually and reproductively.

Political lesbianism emerged as one response—the idea that women should choose lesbianism as political resistance to patriarchy, regardless of their sexual feelings. The Radicalesbians’ 1970 manifesto “The Woman-Identified Woman” argued that lesbianism is the natural end point of feminism, as it withdraws energy from men and redirects it toward women. This position generated intense controversy both within and outside radical feminism, with critics arguing it reduced sexuality to political choice and dismissed lesbian women’s actual desire.

Not all radical feminists adopted these positions on heterosexuality or advocated political lesbianism or separatism. But the willingness to question even intimate sexual arrangements as political rather than natural distinguished radical feminism from more moderate approaches that took heterosexual nuclear families as givens requiring only reform to eliminate discrimination.

Violence Against Women: Making Private Pain Political

Perhaps radical feminism’s most tangible and lasting impact came through politicizing male violence against women. Before second-wave feminism, rape and domestic violence were treated as private matters—shameful secrets women should hide, or problems of individual “bad” men rather than systematic enforcement of male dominance.

Radical feminists argued that male violence against women isn’t deviant behavior by aberrant individuals but a tool through which patriarchy maintains control. All women live under threat of male violence, which constrains behavior even for women never personally victimized. The fear of rape limits where women go, when they go out, what they wear, how they interact with men. Domestic violence keeps women trapped in relationships and demonstrates the consequences of challenging male authority. Sexual harassment enforces women’s subordination in workplaces and public spaces.

Susan Brownmiller’s “Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape” (1975) argued that rape is not about sexual desire but about power and control, and that the threat of rape keeps all women subordinate even though not all men rape. This reframing transformed how rape was understood—from a sex crime committed by deviant individuals to a political act enforcing patriarchy.

Radical feminists created the first rape crisis centers, domestic violence shelters, and hotlines for women escaping abuse. They lobbied for legal reforms changing how the justice system handled sexual assault—eliminating requirements for corroborating witnesses, preventing defense attorneys from using victims’ sexual histories, recognizing marital rape as a crime. These practical achievements benefited millions of women regardless of whether they identified with radical feminism.

The anti-pornography movement emerged from radical feminist analysis that pornography isn’t just sexually explicit material but propaganda for male dominance, eroticizing women’s subordination and degradation. Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin argued pornography harms women both through its production (which may involve coercion and abuse) and through teaching men that women enjoy subordination, thereby increasing violence. They proposed ordinances defining pornography as civil rights violation, allowing women to sue producers and distributors.

This anti-pornography position generated fierce debate within feminism, with “sex-positive” feminists arguing that conflating pornography with violence denies women’s agency and sexual autonomy. The “feminist sex wars” of the 1980s divided radical feminists from liberals over pornography, sex work, BDSM, and other sexual practices, with each side accusing the other of serving patriarchy—either through puritanism or through capitulation to male definitions of liberation.

Famous Phrases and Slogans

“The personal is political” stands as radical feminism’s defining slogan, capturing the movement’s core insight that intimate life is structured by political power. What happens in bedrooms and kitchens isn’t separate from politics but is politics—the most fundamental politics, where male dominance is most naturalized and therefore most invisible. This phrase licensed analyzing and politicizing everything from division of household chores to sexual practices to emotional labor.

“Sisterhood is powerful” expressed solidarity among women across differences, the idea that women share enough common experience of patriarchal oppression to unite politically. The phrase became the title of Robin Morgan’s 1970 anthology collecting radical feminist writings. It emphasized women’s collective strength and the power of women organizing together rather than seeking male approval or permission.

“A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle” became an iconic slogan, often misattributed to Gloria Steinem but actually created by Australian Irina Dunn. The phrase expressed radical feminism’s rejection of women’s supposed natural dependence on men, asserting women’s complete self-sufficiency. Its humor made it memorable while its message was deadly serious—women don’t need men for anything essential, and believing otherwise reflects patriarchal ideology.

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” comes from Audre Lorde’s 1979 essay, though Lorde identified as Black lesbian feminist rather than primarily radical feminist. The phrase captured radical feminism’s skepticism about working within existing systems. You can’t achieve liberation using the oppressor’s methods and frameworks—you need entirely new tools, new structures, new ways of organizing social life.

“Rape is about power, not sex” summarized radical feminist reframing of sexual violence as political enforcement of male dominance rather than expression of uncontrolled male desire. This understanding transformed rape prevention efforts, legal approaches, and public discourse about sexual assault.

“Behind every great man is a woman rolling her eyes” updated the patronizing phrase about great men’s supportive wives, expressing radical feminist frustration with women being expected to support male achievement while their own ambitions go unsupported. Various versions of this sentiment circulated, all expressing similar critique of how women’s labor—emotional, domestic, sexual—enables men’s success while going unrecognized and unrewarded.

Examples of Radical Feminist Activism

The 1968 Miss America protest, though often misrepresented, exemplified radical feminist direct action. Around 400 women protested the beauty pageant in Atlantic City, arguing it objectified women and reinforced damaging standards. They crowned a sheep “Miss America” to protest how contestants were paraded like livestock. They threw bras, girdles, high heels, makeup, and women’s magazines into a “freedom trash can,” though they never set it on fire despite the persistent “bra-burning” myth. Signs read “Welcome to the Miss America Cattle Auction” and “Can Makeup Cover the Wounds of Our Oppression?”

Take Back the Night marches began in the 1970s, with women marching through streets at night to protest how male violence restricts women’s freedom of movement. The marches asserted women’s right to public space at all hours without fear of harassment or assault. They often featured speak-outs where survivors shared experiences of sexual violence, breaking silence and shame around rape and abuse.

Rape crisis centers and domestic violence shelters represented radical feminism’s most tangible legacy. The first rape crisis center opened in 1972 in Washington, D.C. The first battered women’s shelter opened in 1974 in St. Paul, Minnesota. These services, now numbering in the thousands across North America, emerged directly from radical feminist analysis that male violence required collective response rather than being dismissed as private matters.

Consciousness-raising groups proliferated across the United States and internationally throughout the 1970s. These small groups of women meeting regularly to discuss personal experiences created the grassroots base of radical feminism. Through CR groups, thousands of women who never read feminist theory or attended protests encountered radical analysis of patriarchy and developed feminist consciousness.

The Redstockings’ disruption of New York legislative hearings on abortion in 1969 challenged the fact that panels making decisions about women’s reproductive rights consisted entirely of men. They demanded women testify about their actual abortion experiences rather than men theorizing about women’s needs. This direct action exemplified radical feminist insistence that women should speak for themselves about their lives rather than accepting male expertise about women’s experiences.

Lesbian separatist communities emerged as some radical feminists concluded that liberation required complete separation from men. Women-only communes, music festivals, bookstores, and other spaces created alternatives to male-dominated society. The Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival (1976-2015) became an annual gathering of thousands of women, though it later generated controversy over its policy of only admitting “womyn-born-womyn,” excluding transgender women.

Criticisms and Controversies

Radical feminism faced significant criticism both from outside feminism and from within the movement. Black feminists, beginning prominently with the Combahee River Collective’s 1977 statement, argued that radical feminism’s focus on sex as the primary oppression ignored how race and class fundamentally structure women’s experiences. Black women’s oppression couldn’t be understood through sex alone—it required analyzing interlocking systems of racism, sexism, and economic exploitation.

The critique of essentialism accused radical feminism of treating “women” and “men” as monolithic categories with universal experiences and interests. But women’s experiences vary enormously based on race, class, sexuality, nationality, ability, and other factors. Generalizing about “women’s oppression” based primarily on white, middle-class women’s experiences erased the specific struggles of women of color, poor women, and others with different social locations. This led to the development of intersectionality as a framework recognizing multiple, intersecting systems of oppression.

The biological determinism critique argued that by grounding women’s oppression in reproductive biology—women’s capacity to bear children making them vulnerable to male dominance—radical feminism reproduced problematic assumptions about biological sex determining social destiny. If patriarchy stems from biological difference, how can it be changed? Some critics felt radical feminism inadvertently naturalized male dominance by tying it so firmly to biology.

The treatment of men as an enemy class troubled many feminists who had positive relationships with men in their lives or who believed men could be allies in dismantling patriarchy. Framing gender relations as war between sex classes alienated potential supporters and seemed to foreclose possibilities for coalition and partnership. Some argued this approach was strategically counterproductive even if analytically compelling.

Contemporary conflicts around transgender inclusion have divided feminists invoking radical feminist principles to exclude trans women from women’s spaces and those arguing that such exclusion contradicts feminism’s liberatory goals. Some feminists arguing from radical feminist premises claim that trans women are male and therefore cannot be included in women’s movements or spaces. Others argue this position misunderstands both radical feminism and transgender experience, and that true feminism must include all women, transgender and cisgender alike.

FAQs About Radical Feminism

What is the main goal of radical feminism?

The primary goal of radical feminism is to completely dismantle patriarchy—the system of male dominance they identify as the root cause of women’s oppression. Unlike liberal feminism, which seeks equality within existing systems through legal reform, or socialist feminism, which sees women’s liberation as part of class struggle against capitalism, radical feminism argues that patriarchy itself must be abolished. This requires fundamental transformation of social institutions including marriage, family, sexuality, and reproduction, not just adjusting them to be less discriminatory. Radical feminists want to eliminate gender hierarchy entirely, creating society where women are not subordinated to men in any sphere. Some radical feminists envision this requiring separatism, others believe it can be achieved while women and men coexist, but all agree incremental reform is insufficient—revolutionary change restructuring society from its foundations is necessary.

How is radical feminism different from liberal feminism?

The fundamental difference lies in whether existing systems can be reformed or must be dismantled. Liberal feminism seeks equality for women within current social structures—equal pay, equal representation, equal rights under existing law. It accepts institutions like marriage, family, and capitalism while working to eliminate discrimination within them. Radical feminism rejects this approach as insufficient, arguing these institutions are inherently patriarchal and cannot be reformed, only abolished. Where liberal feminists want equal access to existing power structures, radical feminists want to destroy those power structures entirely. Liberal feminism focuses on individual rights and legal equality; radical feminism focuses on collective liberation and structural transformation. Liberal feminism tends to be more palatable to mainstream society because it doesn’t challenge fundamental social organization; radical feminism deliberately challenges everything, making it more controversial but also, its proponents argue, more honest about what liberation actually requires.

Do radical feminists hate men?

This is a common mischaracterization. Radical feminism analyzes men as a class that benefits from and perpetuates patriarchal dominance, but this class analysis doesn’t equate to personal hatred of individual men. Radical feminists distinguish between men as a political class and individual men, just as Marxists distinguish between the capitalist class and individual capitalists. Many radical feminists have positive relationships with male family members and friends. The analysis is structural, not personal—it’s about systems of power, not individual malice. That said, some radical feminist rhetoric has been hostile toward men, and some feminists do express anger at men collectively for maintaining patriarchy. Critics argue this crosses from political analysis into personal animosity; defenders argue women’s anger at oppression is justified and shouldn’t be policed. Whether radical feminism constitutes “man-hating” depends partly on whether you accept that analyzing men as an oppressor class is legitimate political critique or inherently hostile, and that’s itself contested terrain.

Is radical feminism still relevant today?

Radical feminism’s relevance is contested but its influence persists in multiple ways. Contemporary debates about pornography, prostitution, and surrogacy often divide along lines established in 1970s radical feminist arguments. Anti-violence work that radical feminists pioneered—rape crisis centers, domestic violence shelters, anti-trafficking campaigns—continues serving millions of women. The insight that “the personal is political” shapes how people understand intimate relationships as sites of power. However, contemporary feminism has largely moved beyond radical feminism’s exclusive focus on sex as primary oppression, incorporating intersectional analysis of race, class, sexuality, ability, and other factors. The biological essentialism some radical feminists embraced has been challenged by queer theory and transgender activism. Whether radical feminism remains relevant depends on which aspects you emphasize—its structural critique of patriarchy remains influential, while its specific proposals like separatism or political lesbianism have limited contemporary following. Many contemporary feminists draw on radical feminist insights while rejecting aspects they see as essentialist or exclusionary.

What did radical feminists think about motherhood?

Radical feminists had complex and varying positions on motherhood. Some, like Shulamith Firestone, argued that biological motherhood itself was the basis of women’s oppression—pregnancy and childbirth made women dependent and vulnerable to male control. Firestone controversially proposed that reproductive technology might liberate women by separating reproduction from women’s bodies entirely. Others distinguished between motherhood as biological fact and motherhood as patriarchal institution—the social construction of mothering as women’s destiny, primary identity, and greatest fulfillment. Adrienne Rich made this distinction between “motherhood as experience” (which can be joyful and empowering) and “motherhood as institution” (which serves patriarchy by privatizing child-rearing and making women responsible for reproducing society). Radical feminists generally rejected the idea that all women naturally want or should want children, challenging “maternal instinct” as ideology rather than biology. They argued women should have full reproductive freedom—access to contraception and abortion, freedom to choose childlessness without stigma, and if they do have children, support and resources rather than isolation in nuclear family units.

What is consciousness-raising?

Consciousness-raising (CR) was radical feminism’s distinctive practice and primary method for developing feminist analysis. Small groups of women—typically 6-12—would meet regularly, often weekly, to discuss specific topics like work, family, sexuality, body image, or relationships with men. Rather than experts teaching or leaders directing, CR groups were non-hierarchical, with all women sharing personal experiences. Through comparing stories, women recognized that experiences they’d thought were individual problems actually reflected shared patterns of oppression. A woman who felt inadequate because she couldn’t achieve orgasm during intercourse might discover that many women share this “problem,” leading to collective analysis about how female sexuality has been constructed around male pleasure. CR groups built feminist consciousness—understanding personal experiences as political—and created solidarity through recognizing shared struggle. They also validated subjective experience as legitimate source of knowledge about patriarchy, challenging academic and professional expertise that excluded women’s voices. Thousands of women participated in CR groups during the 1970s, making them the primary means through which radical feminist ideas spread beyond written theory to grassroots practice.

Why did some radical feminists advocate separatism?

Separatism emerged from the conclusion that women cannot achieve liberation while remaining in close proximity to their oppressors. If men as a class benefit from patriarchy and have no incentive to dismantle it, and if male presence in women’s spaces recenters male needs and perspectives, then creating women-only spaces becomes necessary for women’s freedom and feminist organizing. Separatists created women-only communes, businesses, social spaces, and political organizations excluding men entirely. Reasons included: protecting women from male violence; creating spaces where women could develop unfiltered by male judgment; allowing women to direct energy toward each other rather than men; and prefiguring the world separatists wanted to create. Some saw separatism as permanent goal; others as temporary strategy. Lesbian separatism specifically advocated that women withdraw emotionally, sexually, and socially from men, directing love and energy toward women instead. Critics within feminism argued separatism was impractical for most women economically dependent on men or emotionally connected to male family members, and strategically counterproductive by removing feminists from spaces where change must happen. Separatism remained a minority position but influenced broader feminist practice through creating women-only spaces within co-educational contexts.

What is the relationship between radical feminism and transgender rights?

This is currently one of feminism’s most contentious debates. Some feminists invoking radical feminist principles—often called “gender critical” feminists or, by critics, “trans-exclusionary radical feminists” (TERFs)—argue that trans women are male and therefore should be excluded from women’s spaces, sports, and political organizing. They claim radical feminism’s analysis is based on biological sex, making transgender identity claims inconsistent with feminist understanding of gender as oppressive social construction. They worry that prioritizing gender identity over biological sex erases the material reality of female oppression. Others argue this position misunderstands both radical feminism and transgender experience. They point out that radical feminists critiqued biological determinism and emphasized that gender is socially constructed, which supports rather than contradicts transgender people’s experiences. They argue that excluding trans women from feminism reproduces the kind of gatekeeping and essentialism that feminism should oppose. This debate has fractured feminist communities, with arguments becoming heated and polarized. Historical radical feminists themselves hold varying positions—some align with gender critical perspectives, others fully support transgender inclusion—making it impossible to claim a single “radical feminist” position on transgender rights.

Did radical feminism achieve its goals?

This depends on how you define the goals. If the goal was completely dismantling patriarchy and eliminating male dominance, then clearly no—patriarchy persists globally, though its manifestations have evolved. However, radical feminism achieved significant victories. Violence against women is now recognized as serious political and legal issue rather than private matter, with rape crisis centers and domestic violence services available in most communities. Sexual harassment is illegal and socially condemned rather than accepted. Reproductive rights expanded in many countries, though they remain contested and have been rolled back in some places. Consciousness that “the personal is political” transformed how people understand intimate relationships as sites of power. Legal reforms radical feminists advocated—marital rape laws, reformed rape prosecution procedures—have been implemented. The institution of marriage has changed significantly, with more egalitarian relationships possible even if full equality remains elusive. What radical feminism didn’t achieve was fundamental transformation of social organization—capitalism, traditional families, heterosexuality, and male dominance persist, though challenged. Whether this represents partial success or fundamental failure depends on whether you see incremental progress as meaningful steps toward liberation or co-optation that leaves patriarchy’s foundations intact.

Can men be radical feminists?

This question generates debate even among radical feminists. Some argue no—radical feminism is by and for women, analyzing women’s oppression from women’s standpoint, and men cannot occupy that position. Men benefit from patriarchy and therefore cannot truly advocate for its dismantlement, even if they claim to support feminism. Male participation in radical feminist spaces recenters male perspectives and creates pressure to accommodate male feelings rather than prioritizing women’s liberation. This position often uses terms like “pro-feminist” for men who support feminist goals, reserving “feminist” for women. Others argue that while radical feminist analysis emerged from women’s experience and women must lead feminist movements, men can be allies who accept feminist analysis and work to dismantle patriarchy. These feminists distinguish between men claiming authority within feminism versus men doing supportive work—educating other men, challenging misogyny, materially supporting feminist organizing. The stricter position reflects radical feminism’s separatist tendencies and skepticism about male motivation; the more inclusive position reflects strategic judgment that widespread social change requires male participation even if women remain primary agents. Either way, radical feminists agree that men shouldn’t dominate feminist spaces or discourse—women’s voices and leadership must be central.

Radical feminism represents one of the most revolutionary and controversial strands of feminist thought, offering systematic analysis of patriarchy as fundamental system of oppression requiring complete dismantling rather than reform. Emerging from the radical politics of the late 1960s, it challenged not just legal discrimination but the most intimate arrangements of private life—marriage, family, sexuality, and reproduction—as tools of male dominance.

The movement’s core insights—that the personal is political, that women constitute a political class oppressed by men as a class, that male violence enforces patriarchy—transformed how people understand gender relations and power. Radical feminism created the infrastructure of anti-violence work that serves millions of women through rape crisis centers and domestic violence shelters. It pioneered consciousness-raising as method for collective analysis. It refused to accept limitations on what could be questioned or criticized, challenging even institutions considered natural or sacred.

Yet radical feminism has also been criticized for essentialism, for treating women and men as monolithic categories while ignoring race and class differences, for biological determinism, and for seemingly positioning men as irredeemable enemies. Contemporary debates about pornography, prostitution, surrogacy, and transgender rights often replay arguments from 1970s radical feminism, with feminists reaching opposed conclusions while claiming radical feminist heritage. The movement’s legacy is thus complex—profoundly influential in some ways, rejected or substantially modified in others.

What remains vital in radical feminism is its refusal of compromise, its insistence on analyzing root causes rather than treating symptoms, and its recognition that systems of oppression operate even in spaces considered private or natural. Whether you embrace or reject radical feminism’s specific positions, its core questions remain essential: What would it take to truly end women’s subordination? Can equality be achieved within existing institutions or do those institutions require fundamental transformation? How do we balance individual freedom with collective liberation? These questions, which radical feminism forced into feminist discourse, continue demanding answers as struggles for justice persist in new forms decades after radical feminism’s emergence as distinct movement.