We have all seen an optical illusion at some point and have marveled at discovering its curious effects on our perception.

One of those that most tests our abilities to discern between the real and the unreal is the one that uses the so-called Thatcher effect We will explore the origin of this optical illusion and what are the keys to it producing this distortion when we see it.

What is the Thatcher effect?

To talk about the Thatcher effect is to talk about one of the best known optical illusions This is a phenomenon by which, if we modify the image of a human face, turning it 180º (that is, from top to bottom), but keeping both the eyes and the mouth in a normal position, the person who sees it is not able to to see anything strange in the image (or detect something strange, but do not know what), recognizing the face without problems, if it is that of someone famous or well-known.

The curious thing is that when the photograph is rotated and placed back in its standard position, leaving, this time, both eyes and mouth in their opposite position, then it does cause a powerful rejection effect in the person who is seeing it, immediately realizing that there is something disturbing about the image, that it is not what a normal face should be.

But why is it called Thatcher effect, or Thatcher illusion? The explanation is very simple. When Peter Thompson, professor of psychology, was doing experiments modifying faces from photographs for a study on perception discovered this curious phenomenon by chance, and one of the first photographs he used was that of, at that time, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, who was none other than Margaret Thatcher.

In any case, the Thatcher effect is one of the most popular optical illusions, and it is very common to see images of different celebrities altered with this effect on the Internet to surprise the people who observe them with this peculiar alteration of perception.

Causes

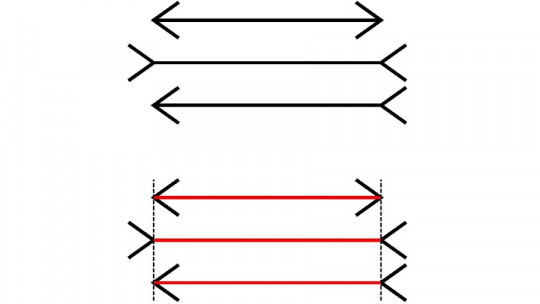

We already know what the Thatcher effect consists of. Now let’s delve into the processes that allow this optical illusion to take place. The key to this whole matter would lie in the mechanisms that our brain uses to identify faces, and that we have been acquiring evolutionarily. We have two visual perception systems to recognize elements in general.

One of them identifies objects (and faces) as a whole, based on the scheme that all their parts make up. Once identified, what our brain does is compare it with the mental database that we have and thus we are able to identify it, if we know it. The other, on the contrary, would focus on each independent element of the object (or the face), trying to identify the global image through its small parts.

In the case of the Thatcher effect, the key would be that, when we flip the image, The first system stops working, since the inverted arrangement of the photograph makes it impossible for us to identify the image in that way This is when the second system comes into play, which analyzes the elements (mouth, eyes, nose, hair, etc.) individually.

This is when the optical illusion occurs, since, although some stimuli are in their normal position and others are turned upside down, individually they do not present anomalies, so they are integrated into a single image, thus making it easier for our brain to identify it as a face. normal, only upside down.

As soon as we rotate the image and put it in its usual position, this time leaving the eyes and mouth upside down, the first identification system is activated again and sets off the alarms when we immediately verify that this image, as we are seeing it, it is impossible. Something doesn’t fit, and we are immediately aware of it, so the Thatcher effect disappears.

Furthermore, another curious effect occurs, and that is that if we have the image with the elements of the Thatcher effect applied (mouth and eyes upside down), in a normal position, and we begin to rotate it very slowly, There comes an exact point at which we stop perceiving the anomaly managing to fool our brain again.

Prosopagnosia

We have seen that the Thatcher effect is possible due to the way our brain system works to identify faces. But what then happens to people who have this altered function? This pathology exists, and is known as Prosopagnosia. The inability to recognize faces, as well as other very varied perceptual alterations, have been explored in the work of Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.

It has been proven that People who suffer from prosopagnosia, and therefore do not recognize the faces of even their most loved ones, are not affected by the Thatcher effect because the recognition and comparison system that we mentioned before does not work in them, and therefore they realize much sooner that there are reversed elements than a person who is not affected by this pathology.

In the previous point we commented that, if the modified image was slowly rotated, from its normal disposition to the flipped position, there was a moment, halfway, when the Thatcher effect suddenly appeared, no longer having that sensation of strange elements before the mouth and eyes. However, people with prosopagnosia do not experience this phenomenon, and they can continue to rotate the image until it is completely flipped without feeling the Thatcher effect.

Animals

But is the Thatcher effect a phenomenon exclusive to human beings? We might think so, given that face recognition is a more developed skill in our species than in any other, but the truth is that no, it is not exclusive to humans. Different studies have been carried out with different types of primate (specifically with chimpanzees and rhesus macaques) and the results are conclusive: they also fall into the Thatcher effect.

When they were presented with images of faces of individuals of their own species, with the parts of the mouth and eyes reversed from their usual position, no variations were noted in the attentional responses compared to those without the elements of the Thatcher effect, which already It suggested that, indeed, they were not realizing the parts that had been turned.

However, when they turned the images over and placed them straight, with the eyes and mouth then inverted, there was greater attention to those images, which showed that in some way they perceived the anomaly, something that was not happening. in the first phase of the study, when the photos were presented upside down.

This makes researchers think that, in reality, The face recognition mechanism is not exclusive to humans as demonstrated in the Thatche effect experiments, but that this mechanism had to originate in a species prior to both ours and these primates, which would be an ancestor of all of them, which is why we would both have inherited this skill, among others.

Other experiments

Once the Thatcher effect and its mechanisms were discovered, researchers began to carry out a series of studies to see how far its reach went, what were the limits that could be placed on this alteration of perception and if it would also work with elements that were not human faces, and even not only with static figures but with animations that represented the movements of people and animals.

In fact, the most diverse versions have been made, some of them rotating letters and words in images with texts, and others in which what is flipped are the pieces of a woman’s bikini. The general conclusions that have been obtained with all these experiments are that the characteristics of the Thatcher effect can be extrapolated to other elements that are not faces but the intensity of the effect obtained will always be less than in the original example.

This is probably because we are especially good at recognizing faces, much more than any other element, which is why we have a specific perception system for this, as we have already described at the beginning of this article. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Thatcher effect is much more noticeable when we work with human faces than if we use any other element instead.