One of the main tasks of philosophy is to investigate the nature of human beings, especially regarding their mental life. How do we think and experience reality? In the 17th century, the debate on this topic had two opposing sides: the rationalists and the empiricists.

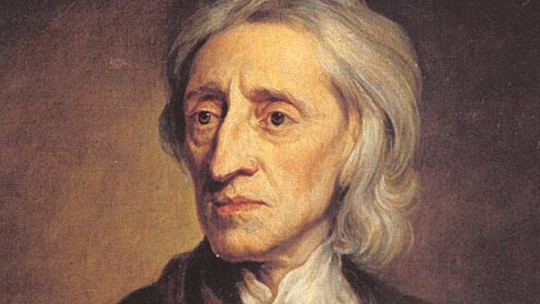

One of the most important thinkers of the group of empiricists was John Locke, English philosopher who laid the foundations of the mechanistic conception of the human being. In this article we will see what were the general approaches to his philosophy and his theory of the tabula rasa.

Who was John Locke?

John Locke was born in 1632 in an England that had already begun to develop a philosophical discipline separate from religion and the Bible. During his youth he received a good education, and in fact he was able to complete his university education at Oxford.

On the other hand, Locke was also interested in politics and philosophy from a young age. It is in the first area of knowledge that he stood out most, and he wrote a lot about the concept of social contract, as did other English philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes. However, beyond politics he also made important contributions to philosophy.

John Locke’s tabula rasa theory

What follows are the foundations of John Locke’s philosophy as it relates to his conception of the human being and the human mind. In particular, we will see What role did the concept of the tabula rasa play in your thinking?.

1. Innate ideas do not exist

Unlike the rationalists, Locke denied the possibility that we are born with mental schemas that provide us with information about the world. On the other hand, as a good empiricist, Locke defended the idea that knowledge is created through experience, with the succession of events that we experience, which leaves a trace in our memories.

Thus, in practice Locke conceived of the human being as an entity that comes into existence with nothing in the mind, a tabula rasa in which there is nothing written.

2. The variety of knowledge is reflected in different cultures

If innate ideas existed, in that case all human beings would share a part of their knowledge. However, in Locke’s time it was already possible to know, even through several books, the different cultures spread around the world, and the similarities between peoples paled before the strange discrepancies that could be found even in the most basic: myths about creation of the world, categories to describe animals, religious concepts, habits and customs, etc.

3. Babies don’t show they know anything

This was another of the great criticisms against rationalism that Locke used. When they come into the world, babies don’t show they know anything, and they have to learn even the most basics. This is evidenced by the fact that they cannot even understand the most basic words, nor do they recognize dangers as basic as fire or cliffs.

4. How is knowledge created?

Since Locke believed that knowledge is constructed, he was obliged to explain the process by which that process occurs. That is, the way in which the tabula rasa gives way to a system of knowledge about the world.

According to Locke, experiences cause a copy of what our senses capture in our mind. Over time, we learn to detect patterns in those copies that remain in our minds, which makes concepts appear. At the same time, these concepts are also combined with each other, and from this process they generate more complex concepts that are difficult to understand at first. Adult life is governed by this last group of concepts which define a form of higher intellect.

Criticisms of Locke’s empiricism

John Locke’s ideas are part of another era, and consequently there are many criticisms that we can direct against his theories. Among them is the way in which he proposes his way of inquiring about the creation of knowledge. Although babies seem ignorant in practically everything, it has been shown that they come into the world with certain predispositions to associate certain types of information from a certain way.

For example, seeing an object allows them to recognize it using touch alone, which indicates that in their heads they are already capable of transforming that original literal copy (the vision of the object) into something else.

On the other hand, knowledge is not composed of more or less imperfect “copies” of what happened in the past, since memories constantly change, or even mix. This is something that psychologist Elisabeth Loftus has already demonstrated: the strange thing is that a memory remains unchanged, and not the opposite.