What influences behavior more: the person or the situation? The same question must have been asked by Philip G. ZimbardoAmerican social psychologist, before beginning his famous study developed in 1971: the Stanford prison experiment.

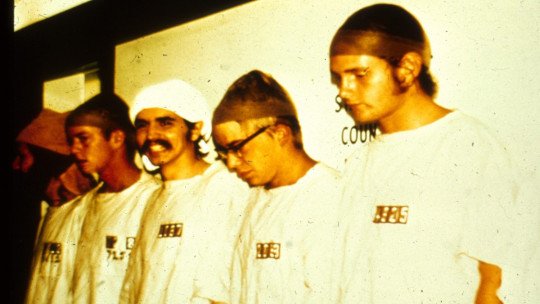

The truth is that the ‘jail’ was actually the basements of the Department of Psychology at Stanford University, set up to temporarily resemble a real prison. Student volunteers participated as actors, randomly assigning the character they had to play as guards or prisoners.

However, the experiment ended prematurely due to its chilling consequences. Prisoners were generally dehumanized by guards through psychological abuse. Up to five prisoners had to leave the program due to anxiety attacks, while the guards became increasingly abusive towards the rest of the prisoners, under the watchful eye of the superintendent: Zimbardo himself.

Nature or context?

The Stanford prison experiment introduced a controlled framework in which to study the adoption of stereotyped roles and the transformation of habitual behaviors carried out by psychologically healthy subjects into very different behaviors that bordered on abuse and revenge (guards) and dehumanization ( prisoners). However: Did the guards act this way by their own nature or was it the prison context that colored the student pacifism of the 70s into despotic behavior? Why did certain prisoners stoically endure psychological abuse when they could have abandoned the experiment at any time?

It is possible that the reader of this article thinks that, being in the role of a participant in the experiment, he would never have acted in such a way because his nature is neither so despotic nor vengeful, as some guards showed, nor so submissive as to endure abuses as a prisoner in a fictitious prison.

In this sense, there is a general tendency to erroneously believe that behavior is given exclusively by the person themselves, that is, due to internal factors (personal, dispositional) of the individual: this is what is known as Central Attribution Error. . In fact, The individual’s behavior is given by internal factors such as motivation, morality or personality, for example, but also by external or environmental factors, such as political and social changes or authority figures, among many others..

In other words: behavior does not depend exclusively on the person, but also on the influences received from the environment in which they find themselves. Thus, the student-guard who acts violently on a classmate in the role of prisoner may find himself under the effects of different internal influences (stress, emotions such as frustration, perfectionist personality traits, etc.) as well as external influences ( pressure from the group of guards to which he belongs, directives dictated by his superior, etc.). Likewise, prisoners are not left behind.

Negative emotions (internal factors) took their toll on them, but also external effects such as, among others, psychological abuse, deprivation of natural light (the prison was still a simple basement) or group pressure (for example , many inmates participated in creating barricades in the cells on the first morning of the second day).

The processes of deindividualization and dehumanization:

The participants in the experiment focused so much on their role that they suffered the so-called ‘deindividualization’ or loss of identity of the subject in favor of the role or role that they had to ‘play’. In this way, the participants acted according to what they believed others expected of their new role:

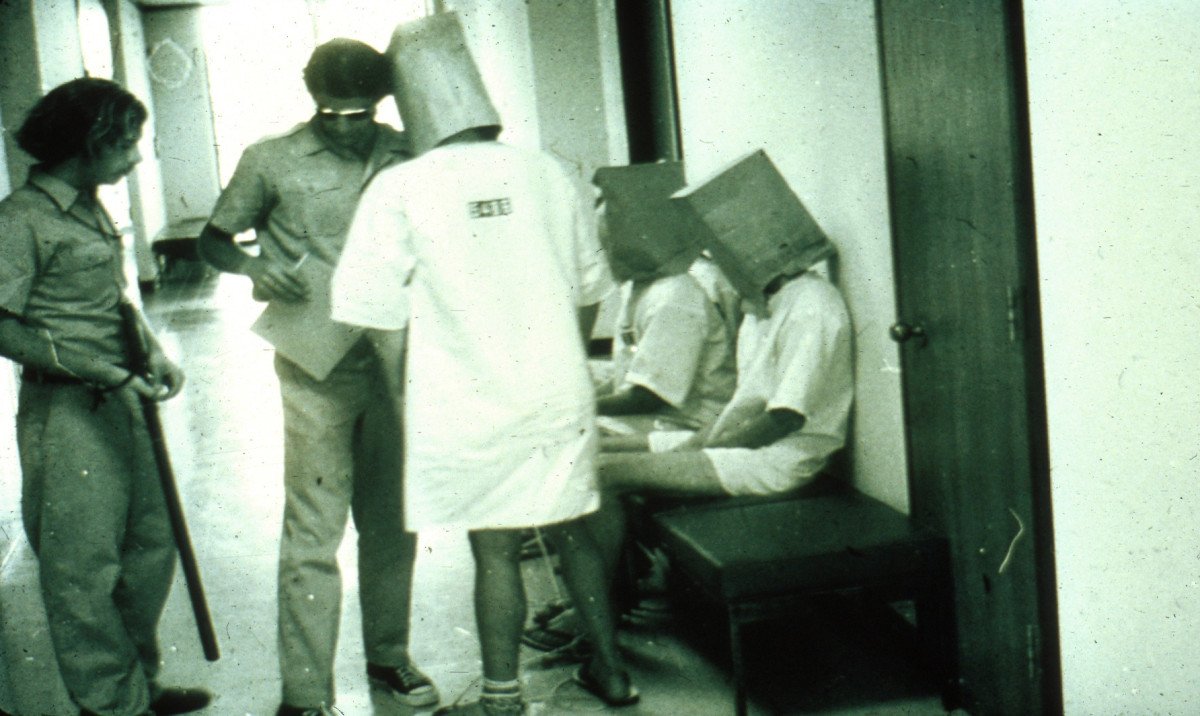

1. The guards

For their part, the guards played a coercive role of surveillance and punishment within the prison. The clothing (uniform, sunglasses) and weapons of deterrence (truncheons loaned by the Stanford police), together with the mental script of how a real prison guard performs in the exercise of his position, allowed peaceful Stanford students to transform into harsh guardians who, in some cases, even dehumanized their fellow ‘prisoners’ (as occurs in terrorist or Nazi ideologies, for example).

Dehumanization is linked to the treatment of other human beings as mere objects (people lose their human characteristics), causing guards to reduce empathy towards prisoners. As is evident, deindividualization contributes to the process of dehumanization itself, as we will see below.

2. The prisoners

The prisoners, forced by the prison context, were assigned reference numbers, wearing the same clothes (prison uniforms, sandals) and even foot chains. The students ended up losing track of time (there were no clocks or windows in the cells), and the symptoms of deindividualization were also evident (they stopped using their names, referring to themselves as the numbers they were assigned).

Although behaviors linked to the survival instinct stand out, such as the betrayal of the group by some of the prisoners in order to receive favors from the guards, the behavioral change experienced by the majority of members of the group seems more remarkable, who went from being revolutionary in the first days (forming barricades, refusing to eat, etc.) to being subjected to psychological abuse: The prisoners had gone from being students carrying out an experiment to being mere numbers serving a non-existent sentence under an inflexible prison regime..

3. The “outsiders”

As for the warden (an associate researcher) and the superintendent (Zimbardo himself), they were also the result of the deindividualization process, coming to believe that they were in their roles within a real prison.

Final thoughts

The Stanford prison experiment offers a detailed example of the central (or fundamental) attribution error we have talked about: the actor is unable to see himself acting (he does not observe his own behavior), focusing exclusively on the environment (the situation in which he is acting). that is found and the behavior of others). For his part, an external observer focuses on both the actors (their behavior) and the environment, even paying more attention to the behaviors developed by the former.

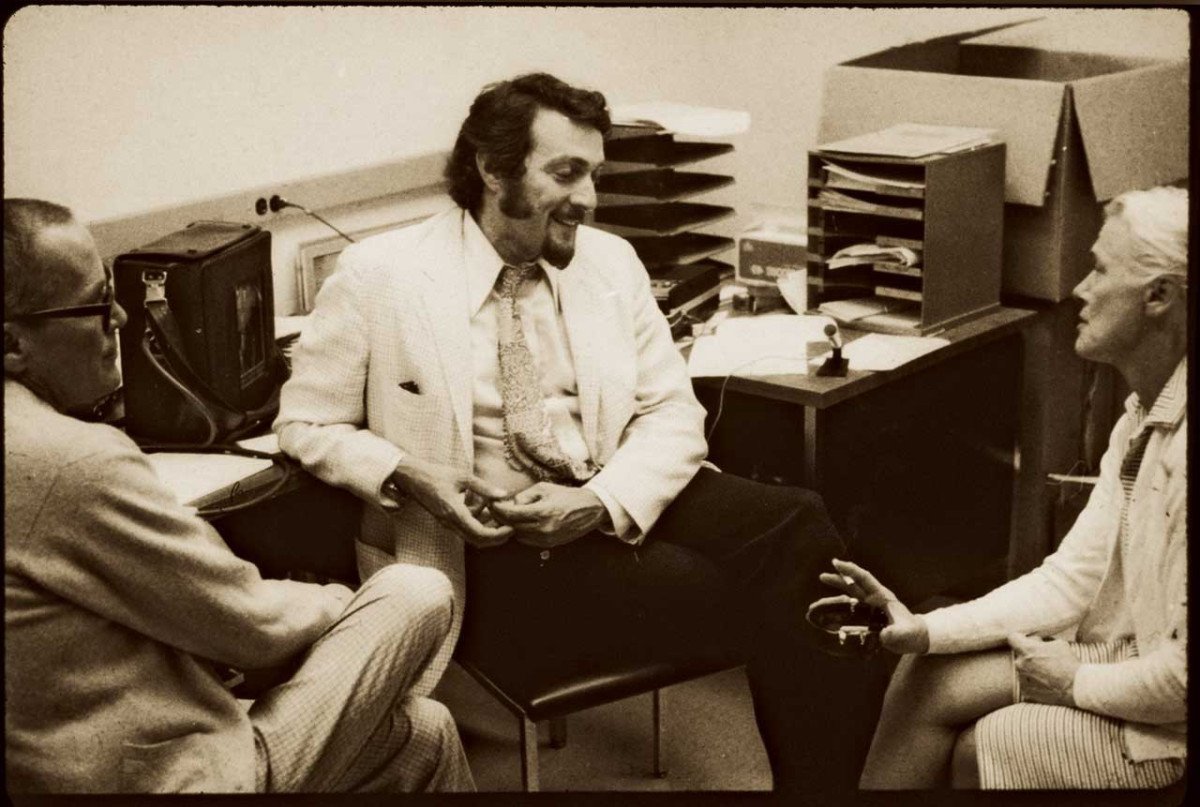

Zimbardo himself is a clear example of this. Immersed in his own role as prison superintendent, he experienced a process of deindividualization that made him focus on the environment (the prison, the behavior of the guards in his charge and the behavior of the prisoners) without taking into account the negative consequences ( suffering) that the decisions about the imprisoned students were causing. It was Christina Maslach, an ‘external observer’, who opened the eyes of Zimbardo, who had left behind his role as a social psychologist to become an inflexible superintendent of prisons.

Despite the results, we must keep in mind that although there were guards who behaved abusively, the narration of the events also mentions the participation of guards who were empathetic with the prisoners and others, although more normatively rigid than the previous ones, more flexible than those considered ‘vengeful’. Perhaps the most paradigmatic case in the study is that of the guard nicknamed ‘John Wayne’, who acted despotically during the experiment.

Likewise, the prisoners, still immersed in the dehumanization process, had different behaviors (collaborators, revolutionaries, subjugated…), depending on various factors. We cannot affirm that the participants were limited exclusively to external factors (the environment, the behaviors of others…), since other internal factors come into play (genotype, cultural traits, morality…) that, together with the external ones, delimit the thoughts and behavior of the subject. Unfortunately, it is not possible to know what factors came into play, at least exactly, in each of the participants at the time of making the decisions that led them to the behaviors shown..

However, what became clear is that when an individual enters a situation, environmental or circumstantial factors affect the subject’s interpretation of the situation (including the behaviors of others). In this sense, prisons are the breeding ground for the appearance of despotic behavior in security guards, who have been deindividualized in the exercise of their position and assigned powers.

In most cases, this type of behavior is controlled by hierarchical superiors (basically non-military personnel), as well as by internal prison rules that, ultimately, defend prison order and the human rights of prisoners, preventing, in part, dehumanization and suffering. Unfortunately, in certain parts of the world, such as what happened at Abu Ghraib in 2004, control of this type of abusive behavior is not always achieved.

It is enough to note that the person responsible for the Stanford experiment, Zimbardo, as a result of the abuses committed by the American soldiers in the Iraqi prison, recalled the events that occurred in his own fictitious prison by publishing the book ‘The Lucifer Effect’ (2007), reaching the conclusion that under stressful circumstances ordinary people can become the most terrible executioners. Never better said.