Catalina de Trastámara, better known in history as Catherine of Aragon, is a very famous figure thanks to the multitude of novels, series and films that have been made about her. In all of them, the queen appears as a secondary character, of course, overshadowed by her husband Henry VIII and, above all, by her “impersonator”, the beautiful and graceful Anne Boleyn.

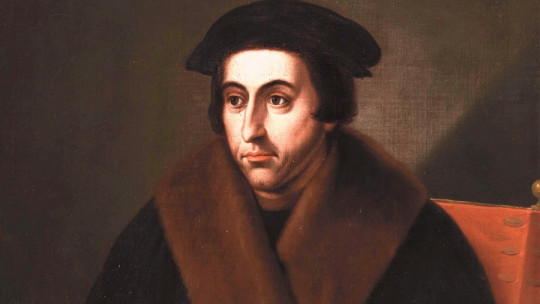

The character of Catherine of Aragon is one of the best examples of the influence that fiction can have on a historical figure. Because, Far from being the prudish queen that we have been shown, Catherine was, possibly, one of the best humanists of the 16th century, whose name deserves to be highlighted on the same page as her male colleagues. We are talking about scholars like Thomas More, Luis Vives or Erasmus of Rotterdam who, by the way, always praised his extraordinary intelligence and enjoyed his protection. Join us to discover one of the most fascinating queens of the Modern Age, far from clichés and legends.

Brief biography of Catherine of Aragon, queen of England

From her birth, Catalina de Trastámara was destined to fulfill a glorious destiny. His parents were none other than Isabel of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon, who had received the title of Catholics. in the bull Si convenit, issued by Alexander VI, the Borgia pope, in 1496.

The title of Catholics did not refer so much to the religion itself as to the universal projection of the reign of Isabella and Ferdinand (from katholikós, “universal”) and, in fact, the marriage policy they initiated was aligned with this idea. The kings agreed to a series of alliances with the European powers of the time, which committed their children to the reigning royal houses.

Thus, in 1479 the marriage of Isabel, the first-born, was agreed upon with the heir to the throne of Portugal, who unfortunately died prematurely, which caused pressure from the Catholic Monarchs on their daughter, who urged her to marry the new monarch, Manuel I. Juan, the only male child of the Catholics, married Margaret of Austria, daughter of Emperor Maximilian, in a masterful move that married, in turn, Philip, Margaret’s brother, to Juana , Juan’s sister. On the other hand, María, born in 1482, married her brother-in-law, Manuel of Portugal, when he was widowed by Isabel, who died when she was only twenty-eight years old.

With our sights set on England

Catherine was the last offspring of Isabel and Ferdinand. When she was three years old, negotiations began for her marriage to Arthur, the Prince of Wales, eldest son of Henry VII of England and heir, therefore, to the English throne. The political strategy of the Catholic Monarchs when projecting this link was, of course, to surround France, the traditional enemy of England, and thus establish a lasting alliance with the Tudors, the family that had recently come to power in the country after the War of the Two Roses. The siege of Charles VIII of France was completed with the connections of Juana and Juan with Felipe and Margaret of Austria, respectively.

Thus, the young Catherine knew from her earliest age about her future in England. Isabel la Católica was very clear about the diplomatic role that her children were going to play in their adopted countries, so she took pains to provide them with an exquisite education that did not differentiate between women and men. Catalina acquired a perfect humanist culture from a very young age, which accompanied her throughout her life. Furthermore, he had a very clear vision about the need for an education that did not discriminate against people based on sex. The prestigious humanist Juan Luis Vives (1492-1540) dedicated a book to her that deals with this last topic, De institutione Feminae Christianae (On the instruction of the Christian woman), which was a reference book for the education of Mary, Catalina’s daughter. and Henry VIII.

Educated among humanists

This is, precisely, one of the topics that it is urgent to discard about Catherine of Aragon: her “obsession” with the topic of faith that, supposedly, left other concerns aside. Yes, the queen was a very religious person, of course. In fact, like all those close to him. In the 16th century it was inconceivable not to follow a religion, since life was understood only from a spiritual perspective. If we had asked an early modern person if they were an atheist, they would most likely not know what we were referring to.

That being said, the fame with which a character like Catalina has gone down in history is really unfair. By losing sight of her intellectual activity and her unconditional protection of figures of the stature of Erasmus of Rotterdam, Thomas More and Luis Vives (who always spoke of her with praise and who belonged to the queen’s close circle), and by focusing exclusively on his religious “stubbornness” (reflected in his absolute rejection of divorce from Henry VIII), we are omitting a very important part of this character, without which it is impossible to understand his entire personal and historical dimension.

We have already said that Catalina was exquisitely educated at the request of her parents, like the rest of her siblings. She was educated by the humanist Alessandro Geraldini (1455-1524), who immersed her in various studies, such as arithmetic, history and classical literature, readings that, by the way, They allowed him to speak Latin with extraordinary fluency, a language he mastered along with Spanish, French and Greek.

On the other hand, Catherine also received theological instruction, musical knowledge, dance, sewing, lace and even heraldry. All of this came together so that the youngest of the Catholic Monarchs became a true humanist, whom contemporary English stories describe as one of the most prepared queens of her time.

Princess of Wales… widow

That was the Catherine who, at only sixteen years old, finally arrived on English soil, after an arduous journey in which, according to witnesses, she suffered real illnesses. It was the month of October 1501; An English delegation arrived in Plymouth to welcome the new Princess of Wales.

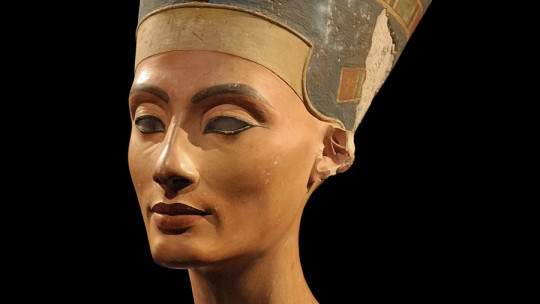

The Anglo-Saxon chronicles are very enthusiastic when it comes to portraying the wife of their Prince Arthur. It was said that she had beautiful skin, white and delicate, and long, beautiful hair, between blonde and reddish, which perfectly followed the canons of feminine beauty of the time. On the other hand, and despite the fact that Catalina was short (although taller than her fiancé, who at fifteen years old still looked like a child), she had pretty features in a sweet oval face.

In short, the princess greatly pleased her new people and, especially, her future husband, who was dazzled by her from the beginning. The official wedding took place on November 14, 1501, a couple of days after Catherine’s arrival in London. It seemed that fate predicted happy times for England and the new Tudor dynasty.

However, just a few months after the marriage, Arturo became seriously ill (several possibilities are being considered, but the most accepted is that he suffered from what was known as the “English sweat”, an extraordinarily deadly disease). Catalina fell ill in turn, and, in her convalescence, she did not learn of the sad death of her husband, who was leaving the world at only fifteen and a half years old. Catherine was now Princess of Wales… a widow.

Queen of England

Henry VII was faced with a political problem. To begin with, he had not yet received the entire dowry promised by Fernando for his daughter’s marriage to Arturo. On the other hand, it was unthinkable to return Catherine to her homeland, since that would mean a break (and not a friendly one) between the cordial relations that England maintained with Castile and Aragon. Yes, it is true that there was a third option: for the widow to marry Enrique, the younger brother of the deceased. But there was still the problem of dowry; Henry VII did not wish to remarry one of his sons to a young princess who could not (or would not) pay what she owed.

As it was, the situation dragged on indefinitely. Catherine continued to live in England as a widowed princess, but her conditions were desperate. Numerous letters to his father are preserved in which he complains that he hardly has money to buy food and clothes, which was added to the humiliation of being treated by the English monarch almost like someone giving alms. All of this made her aura as a “humiliated” princess grow, which undoubtedly had a lot to do with the fascination that, at first, she exerted on Enrique, Arthur’s chivalrous and ardent younger brother.

The situation became unsustainable, and Catalina, desperate, announced her intention to return to Castile and retire to serve God. But the wheel of Fortune seemed to smile at him, and turned in his favor. A few days before her planned departure, the old king died, leaving her the way clear to marry Henry, the new monarch. The wedding finally took place in April 1509; he was a splendid eighteen years old; The bride was a beautiful maiden of twenty-three years. The future couldn’t look brighter.

A male heir is urgently needed

All historians agree on how much Henry loved his wife during the first years of their life together. The affection is logical if we think that the monarch was also a quite cultured man, and the wife he had been given was one of the most erudite in Europe. On the other hand, Catalina was still a pretty and pleasant woman and, furthermore, the seven years that had passed since Arturo’s death had strengthened the relationship between the two boys.

We have historical testimonies that more than demonstrate the trust that Enrique had in his wife. For example, in 1513 he appointed Catherine governor while he was fighting in France. Not only that, but he made her captain general. The queen gave herself fully to her responsibility, which was not small, since it involved protecting England from the enemy army, a task that she successfully resolved. That is to say, in addition to being intelligent, Catalina was an excellent strategist.

After the birth of a first daughter, who was stillborn in January 1510, the long-awaited son, Enrique, arrived, who, unfortunately, only survived two months. These misfortunes were followed by several more; Catherine gave birth to several stillborn children over the next eight years. Of all the births, the only one to survive to adulthood (and actually become queen) was Mary Tudor, better known by the unpleasant nickname Bloody Mary.

The lack of a male heir began to sour what, at first, had been an affectionate union. Enrique began to frequent lovers, although none had “importance” beyond a passing interest. Everything changed when, in 1525, Henry fell madly in love with Anne Boleyn, one of the queen’s ladies-in-waiting, who had returned from the court of Queen Claudia of France a refined, cheerful and extraordinarily attractive lady.

The beginning of the end

Of course, and regardless of what the romantic chronicles claim, it was not only Henry’s love for Anne that motivated the so-called Anglican schism. Several factors came together, among them, the one that probably had the most weight: the lack of a male heir, which Enrique began to attribute to divine punishment.

To understand this royal remorse, it is necessary to go back to Catherine’s marriage to Henry. The pope had granted a dispensation for the celebration of the union, since Catherine had been married to her husband’s brother and, according to Leviticus, this type of union was strictly prohibited by the law of God. The issue was thorny, since, in another book of the Bible, Deuteronomy, the brother of the dead man was directly obliged to take care of the widow as his wife. The controversy, therefore, was served, although, de facto, the papal dispensation should have been enough to stop any discussion.

The real problem was that, in the same dispensation, the pope was somewhat ambiguous, as he spoke of the fact that Catherine forsitan’s first marriage (that is, “perhaps”) had not been consummated. This left the last word to the widow, since the husband, who could also give his opinion on the matter, had died.

Catalina always defended that, despite having shared a bed with Arturo on certain occasions (which were not many, since the teenagers lived apart for much of their fleeting marriage) her husband “had not known her,” a common expression at the time for talk about a man and a woman who had not had sexual relations. And since, under canon law, a marriage without relations could be considered null, the fact of having “known” carnally was crucial to granting validity to the union.

This, of course, did not help Enrique’s cause at all. If Catalina had indeed not maintained relations with her brother, this meant that his wife’s first marriage was void and, therefore, his was valid. Catherine always defended that she had arrived at Henry’s bed a virgin and, in fact, he himself boasted to his friends (before the Boleyn affair) that, indeed, he had “deflowered” his wife on their wedding night. Was Henry lying, then, when he insisted on the fact that Catherine had slept with his brother? Was he lying so he could pressure the Pope to declare his marriage null and void, so he could marry Anne Boleyn?

Be that as it may, everyone knows that, Finally, the monarch ended up cutting relations with the Holy See and proclaiming an independent Church in England, of which the king was the sole and absolute head. This allowed him to undo the marriage with the daughter of the Catholic Monarchs and marry his lover who, in the end, did not give him a son either and he ended up on the scaffold, accused of committing incest with his own brother (accusations that, on the other hand, side, they had no foundation).

As for Catherine, she ended her days in Kimbolton Palace, almost imprisoned (a fact that sadly reminds us of the fate of her sister Joan). He died at the age of fifty, probably a victim of aggressive cancer. Until the end of her life she defended her cause and maintained the validity of her marriage to Enrique. Did her deep religiosity lead her to act like this? Yes, but also her acute sense of dignity and her courage, which made her face tooth and nail the lie that had been spun against her. An intelligent, firm and brave woman who was much more than the prudish queen that they have sold us throughout history.