Osteoarthritis is one of the most common joint diseases, especially in people over 45 years of age, and significantly affects the quality of life of those who suffer from it. It is characterized by the wear of the cartilage that covers the joints, generating pain, stiffness and limitation in movement. However, a new study has revealed an underexplored aspect of this disease: the brain’s influence on the body’s ability to activate muscles and protect joints.

Traditionally, osteoarthritis has been understood as a purely physical problem, related to the deterioration of the joints. However, researchers have discovered that the brain also plays a key role in muscle inhibition, preventing muscles from activating efficiently. This brain mechanism, which initially seeks to protect the joint, ends up being an obstacle to rehabilitation.

This finding opens new opportunities for the treatment of osteoarthritis, suggesting that, in addition to strengthening muscles, it is crucial to address the brain’s response to chronic pain. Understanding this connection could revolutionize therapeutic approaches, offering more complete and effective solutions for patients suffering from this condition.

What is osteoarthritis and how does it affect the body?

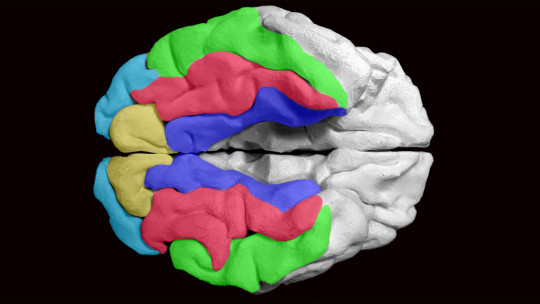

Osteoarthritis is a degenerative disease that mainly affects the joints, such as the knees, wrists, hands and hips. It is characterized by the progressive wear of the cartilage that covers the ends of the bones, which causes friction and deterioration in the joint. As the cartilage wears away, the bone becomes more exposed, leading to pain, inflammation, and loss of mobility. This condition is common in people over 45 years of age and its prevalence increases with age.

In the case of the hip specifically, osteoarthritis is particularly debilitating. People who have hip osteoarthritis may experience difficulty performing basic movements, such as walking, climbing stairs, or getting up from a chair. Over time, the joint becomes stiff and the ability to move fluidly is compromised. This not only affects patients’ quality of life, but can also lead to loss of muscle mass due to lack of use, further exacerbating the problem.

The main symptoms of osteoarthritis include chronic pain, which often worsens with movement, morning stiffness that decreases with movement, and inflammation in the affected area. Additionally, many people with this disease adopt abnormal postures or movement patterns to avoid pain, which can lead to more long-term physical problems.

The impact of osteoarthritis goes beyond physical damage. Chronic pain and limitations in daily activities can also affect patients’ emotional well-being, generating feelings of frustration, anxiety or depression. This makes osteoarthritis a disease with great impact on people’s lives, both physically and psychologically.

The role of the brain in muscle activation

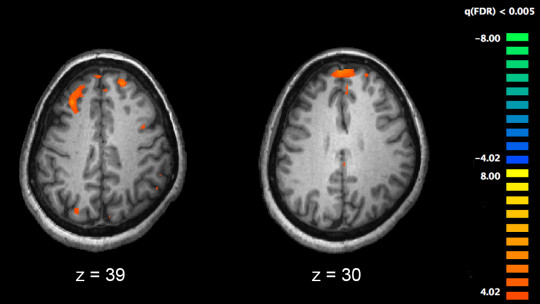

One of the most surprising findings of the new Edith Cowan University study is the crucial role the brain plays in muscle activation in people with hip osteoarthritis. Traditionally, it has been assumed that joint pain and stiffness derived exclusively from their physical deterioration. However, this study has revealed that The inability to activate muscles efficiently depends not only on physical strength, but also on how the body regulates this activity.

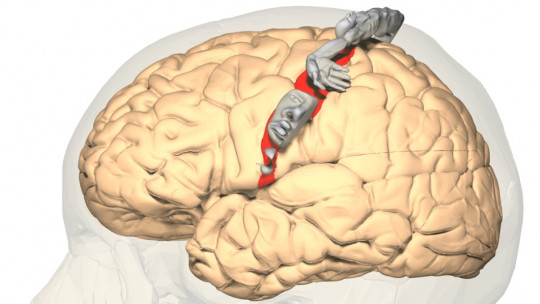

The study shows that in people with hip osteoarthritis, the brain appears to act as a kind of brake that prevents the muscles from fully activating. This is crucial, since muscle activation is essential for joint protection and pain reduction. Without proper muscle activation, the affected joint is left more vulnerable to damage, which can worsen symptoms and make the rehabilitation process more difficult.

This phenomenon suggests that the brain’s response to chronic pain is different than previously thought. Instead of allowing muscle activation to stabilize the joint, the brain seems to block this process possibly as a way to “protect” the affected area.

The researchers suspect that this protective response is useful in the short term, as might be the case in acute injuries such as a sprained ankle or banged knee. However, in the case of osteoarthritis, where the pain is chronic, this brain mechanism can become counterproductive, preventing the correct rehabilitation of patients.

The fact that the brain influences muscle activation so much raises important questions about how osteoarthritis treatment should be approached. If the brain is inhibiting muscle movements, treatments that only focus on strengthening muscles may not be enough. Understanding this brain-muscle relationship could open new avenues to develop therapies that not only strengthen the muscles, but also modify the brain response, thus improving results in the rehabilitation of patients with osteoarthritis.

The brain as a defense mechanism against osteoarthritis

The study also suggests that the brain acts as a defense mechanism against pain and joint damage in osteoarthritis, but this response can become problematic. In normal situations, the brain sends signals to the muscles to activate and protect the joints. However, in people with osteoarthritis, this mechanism seems to be altered: the brain, instead of allowing muscle activation, inhibits it. This response, which in principle would be protective, becomes an obstacle to recovery.

The researchers hypothesis is that this response originates as a way to protect the joint in the short term. In acute injuries, such as a sprain or bruise, the brain sends signals that limit movement to prevent further damage. However, In the case of osteoarthritis, where the pain is chronic, this response is maintained for a long time, which prevents the proper use of the muscles. Instead of helping to protect the joint, this prolonged inhibition of the brain ends up being counterproductive.

This brain “brake” not only affects muscle activation, but also the person’s ability to perform everyday activities, such as walking or getting up from a chair. In the long term, this pattern of inhibition can lead to greater muscle atrophy and more rapid progression of the disease, creating a vicious cycle where pain and muscle dysfunction feed on each other.

This discovery highlights the importance of approaching osteoarthritis from a broader perspective, one that not only considers the physical wear and tear of the joints, but also the role the brain plays in perpetuating pain and functional limitation. Understanding this maladaptive response is key to designing more effective treatments in the long term.

Implications of the study for the treatment of osteoarthritis

The findings of this study open new possibilities for the treatment of osteoarthritis, by showing that it is not only a physical problem of joint wear, but also a phenomenon that involves the brain.

Traditionally, osteoarthritis therapies have focused on strengthening the muscles around the affected joint. and improve mobility through exercises and physical therapy. However, this study suggests that these interventions could be insufficient if the inhibitory role that the brain plays in muscle activation is not taken into account.

1. Brain training

A possible implication of this discovery is the development of therapies that not only focus on the muscles, but also on training the brain to allow proper muscle activation. This could include interventions that combine physical rehabilitation techniques with neurological or cognitive approaches, such as neurofeedback therapy or non-invasive brain stimulation. These strategies would aim to modify the brain response, allowing the muscles to activate correctly to protect the joints and relieve pain.

2. Pharmacological or psychological treatment

Besides, These findings could influence the design of pharmacological treatments or psychological interventions to address the management of chronic pain. helping to prevent maladaptive brain inhibition that aggravates osteoarthritis. In summary, this study points to the need for integrated approaches that consider both the physical and neurological aspects of the disease, which could significantly improve the quality of life of patients with osteoarthritis.

Conclusions

The Edith Cowan University study reveals a new perspective on osteoarthritis: the influence of the brain on muscle activation. This finding underlines that the disease not only physically affects the joints, but also involves a brain mechanism that inhibits muscle function, making recovery difficult. Addressing osteoarthritis from this comprehensive view, combining physical and neurological therapies, could significantly improve rehabilitation results. This advance suggests that the future of treatment must consider both the body and the mind to offer more effective solutions to patients.