There was a time when it was not known what caused diseases. There were those who thought they were due to celestial designs, others due to miasmas, and others due to the position of the stars.

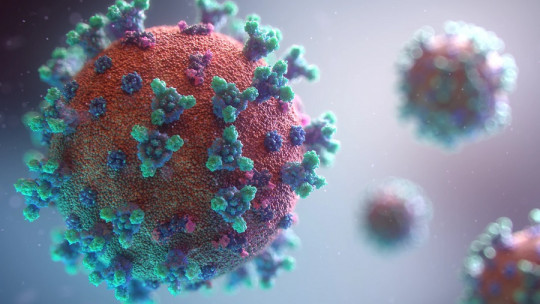

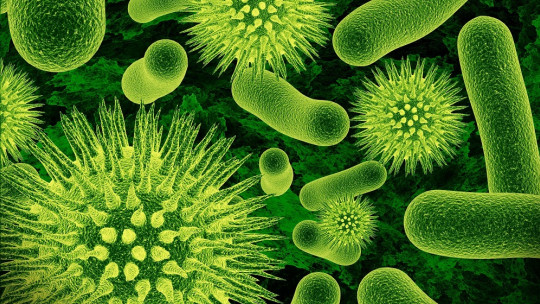

Robert Koch, together with other scientists, discovered that many diseases had an infectious origin, that is, they were caused by pathogens, such as bacteria.

Based on this, he proposed several statements, called Koch’s postulates, which have acquired great importance in the history of microbiology and in the study of infectious diseases. Below we will see why, and what exactly these postulates say.

What are Koch’s postulates?

Koch’s postulates are four criteria that were designed to establish the causal relationship between pathogenic agents, mostly microbes, and diseases They were formulated in 1884 by the German doctor Robert Koch, in collaboration with Friedrich Loeffler, based on concepts previously described by Jakob Henle. It is for this reason that they are also known as the Koch-Henle model. The postulates were presented in 1890 at the International Congress of Medicine in Berlin for the first time.

These postulates They have been a great milestone in the history of medicine, and have contributed to microbiology rearing its head Furthermore, it marked a before and after in the history of medical sciences, given that Koch’s proposal has been considered an authentic bacteriological revolution, allowing us to understand the relationship between pathogenic agents and diseases. Before this model, many people, including doctors and scientists, believed that diseases could be caused by celestial designs, miasmas, or astrology.

Despite all this, with the passage of time they ended up being revised, proposing updates more adapted to the scientific knowledge of the following century. Besides, The original conception of these four postulates had certain weaknesses which made even Koch himself aware that he would have to delve deeper into the study of infectious diseases.

Which are?

Koch’s original postulates were three when they were first presented at the Tenth International Congress of Medicine in Berlin. The fourth was added in later revisions:

1. First postulate

“The microorganism should be found in abundance in all organisms that are suffering from the disease, but it should not be found in those that are healthy.”

This means that if a microbe is suspected of being the causative agent of a particular disease, It should be found in all organisms that are suffering from said disease, while healthy individuals should not have it

Although this postulate is fundamental within Koch’s bacteriological conception, he himself abandoned this universalist conception when he saw cases that broke this rule: asymptomatic carriers.

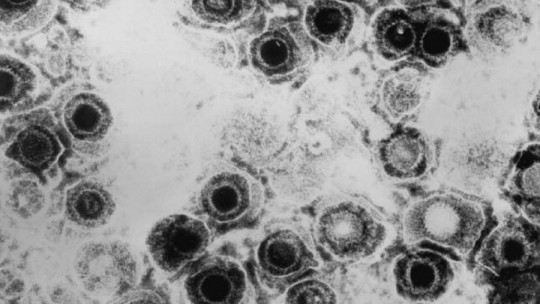

Asymptomatic people or people who have very mild symptoms are a very common phenomenon in several infectious diseases Even Koch himself observed that this occurred in diseases such as cholera or typhoid fever. It also occurs in diseases of viral origin, such as polio, herpes simplex, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C.

2. Second postulate

“The microorganism must be able to be extracted and isolated from a diseased organism and grown in a pure culture.”

The experimental application of Koch’s postulates begins with this second statement, which says that if there is a suspicion that a microbe causes a disease, this should be able to be isolated from the infected individual and cultured separately for example, in an in vitro culture with controlled conditions.

This postulate also stipulates that the pathogenic microorganism does not occur in other infectious contexts, nor does it occur by chance. That is, it is not isolated from patients who have other diseases, in which it can be found as a non-pathogenic parasite.

However, This postulate fails with respect to viruses, which, given that they are obligate parasites, and taking into account the techniques of the late 19th century, it was not possible to extract them for cultivation under controlled conditions. They need cells to live in.

3. Third postulate

“The microorganism that has been grown in a culture should be able to cause the disease once introduced into a healthy organism.”

That is, according to the Koch-Henle model, if a bacteria has been grown in a culture and is present in the appropriate quantity and stage of maturation to cause a pathology, When inoculated into a healthy individual it should cause the disease

When introduced into a healthy individual, the same symptoms that occur in sick individuals from whom the pathogen was extracted should be observed over time.

This postulate, however, is formulated in such a way that “should” is not synonymous with “always should be.” Koch himself observed that In diseases such as tuberculosis or cholera, not all organisms that were exposed to the pathogen were going to cause the infection

Today it is known that the fact that an individual with the pathogen does not show the disease may be due to individual factors, such as having good physical health, a healthy immune system, having been previously exposed to the agent and having developed immunity to it. him or, simply, having been vaccinated.

4. Fourth postulate

“The same pathogen should be able to be re-isolated from individuals from whom it was experimentally inoculated, and be identical to the pathogen extracted from the first diseased individual from which it was extracted.”

This last postulate It was later added to the Berlin Medical Congress in which Koch presented the three previous postulates It was added by other researchers, who considered it relevant, and basically stipulates that the pathogen that caused the disease in other individuals should be the same one that caused the first cases.

Evans Review

Almost a century later, in 1976, Sir David Gwynne Evans incorporated some updated ideas on epidemiology and immunology into these principles especially on the immunological response of the hosts triggered by the presence of an infectious microorganism.

Evans’ postulates are the following:

Limitations of the Koch-Henle model

You have to understand that The postulates, although they represented an important milestone that accentuated the bacteriological revolution, were conceived in the 19th century Taking into account that science usually advances by leaps and bounds, it is not surprising that Koch’s postulates have their limitations, some of them already observed in his time.

With the discovery of viruses, which are acellular pathogens and obligate parasites, along with bacteria that did not fit the Koch-Henle model, the postulates have had to be revised, an example of which is Evans’ proposal. Koch’s postulates They are considered fundamentally obsolete since the 1950s, although there is no doubt that they have great historical importance

Another limitation is the existence of pathogens that cause different diseases from individual to individual and, also, diseases that occur with the presence of two different pathogens, or even individuals who have the pathogen but will never manifest the disease. That is to say, it seems that the pathogen-disease causal relationship is much more complex than what the model initially proposed, which conceived this causal relationship in a much more linear way than today we know that diseases and their relationship occur. with pathogenic agents.