Viruses are infectious agents that have the peculiarity that they are not considered life forms per se.

The main reason why they are not considered living beings is that, in addition to not having the basic unit of every organism, the cell, they require the existence of an organism to be able to reproduce. They are not capable of replicating on their own.

Next we will see the cycle of viral replication which will allow us to understand why viruses are so particular and what makes them so extremely strange.

How does a virus reproduce?

The virus replication cycle is the term used to refer to the reproduction capacity of these infectious agents Viruses are acellular forms, that is, they lack cells, something that all organisms do have, whether they are prokaryotes or eukaryotes and whether they have only one of them or, as is the case with animals, millions. Pathogens such as bacteria, no matter how small they are, contain at least one cell and are therefore living beings.

The cell is the morphological and functional unit of every living being and is considered the smallest element that can be considered a living being itself. It performs several functions: nutrition, development and reproduction.

Viruses, since they do not contain this type of structure nor are they a cell, are not considered living beings, in addition to being They are not capable of carrying out the three basic functions of every cell on their own They require a cell to carry out these functions. This is why their reproductive cycle is so surprising, given that, since they cannot carry it out on their own, they require a form of life to be able to multiply. They are agents that cannot continue to exist without the action of an organism.

Viral replication and its stages

The viral replication cycle consists of the following phases: attachment or absorption, penetration, undressing, multiplication and release of new viruses.

1. Fixation or absorption

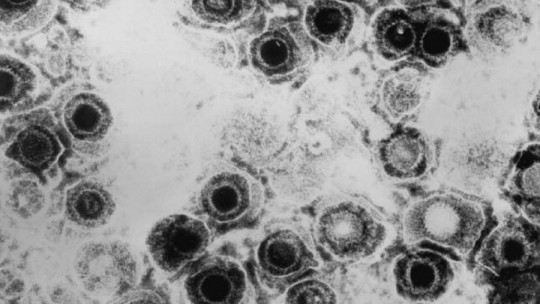

The first step for viral infection, which will culminate in its multiplication, is the fixation of the pathogenic agent in the cell membrane where the entire process will take place. Attachment is carried out by means of viral ligands, which are proteins found in the geometric capsule of the virus, called the capsid.

These proteins interact with specific receptors on the surface of the cell that will act as a “squatter” for the virus Depending on the degree of virus-receptor specificity, the virus will be more or less successful in carrying out the infection.

2. Penetration

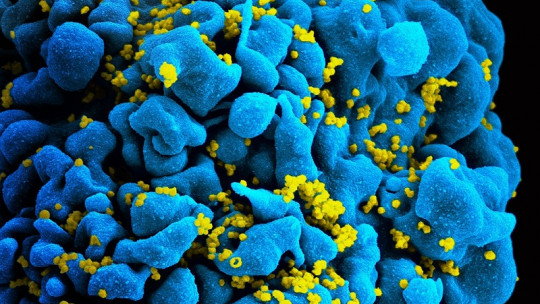

Once bound to the cell surface receptor, Viruses induce changes in their capsid proteins, which leads to the fusion of the viral and cell membranes Some viruses contain DNA (viral DNA), which can enter the cell through endocytosis.

In order for it to enter the interior of the cell, this viral DNA requires that the membrane has been broken and, there, an anchoring point for the virus is established. This is possible through hydrolytic enzymes found in the capsid.

Through the break, the virus introduces a central tube with which will inject its viral DNA, emptying its capsid and introducing its contents into the cytoplasm, that is, the aqueous medium inside the cell. If a cell contains capsids on its cell surface, this indicates that the cell has been infected.

It should be said that there are also viruses that do not carry out this process identically. Some are introduced directly into the cell with their capsid and all. This is where we can talk about two types of penetration.

There are viruses that have a lipid envelope, which is of the same nature as the cell membrane This makes the cell prone to fusing its membrane with that of the virus and endocytosis occurs.

Once inside the cell, the capsid, if it has remained intact, is eliminated and degraded, either by viral enzymes or those of the host organism, and the viral DNA is released.

3. Stripping

It is called stripping because the virus, if introduced into the body, loses its capsid and exposes its internal material, as if it were stripped naked Depending on the duration of the synthesis phase, two modalities of the viral infection cycle can be distinguished.

On the one hand, we have the ordinary cycle The viral DNA immediately proceeds to transcribe its genetic message into the viral RNA, necessary for its multiplication, and this is where reproduction itself would begin. This is the most common modality.

On the other hand, there is the lysogenic cycle The viral DNA closes at its ends, forming circular DNA, which is similar to that of prokaryotic organisms. This DNA is inserted into the bacterial DNA, in a region where they have a similar nucleotide chain.

The bacteria continues to carry out its vital functions, as if nothing were happening. When bacterial DNA duplicates, the viral DNA attached to it will also do so becoming part of the DNA of the two daughter bacteria.

In turn, the daughter bacteria will be able to have their offspring and so on, causing the viral DNA to also multiply with each bacterial replication.

This viral DNA will detach from the bacteria’s DNA when the right conditions are met for this continuing with its remaining infectious phases and producing new viruses while contributing to the death of the bacteria.

The lysogenic cycle can also occur in viruses that affect animal cells, such as the wart papillomavirus and some retroviruses that are involved in oncological diseases.

4. Multiplication

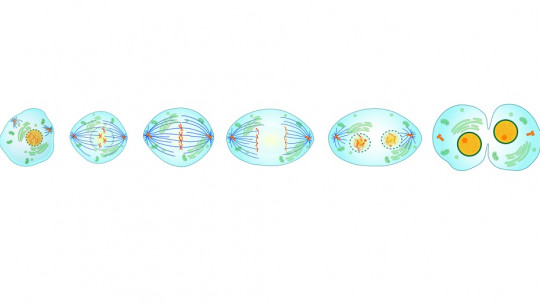

Although we have already introduced it in the undressing phase, the virus multiplication phase is the one in which its actual replication occurs.

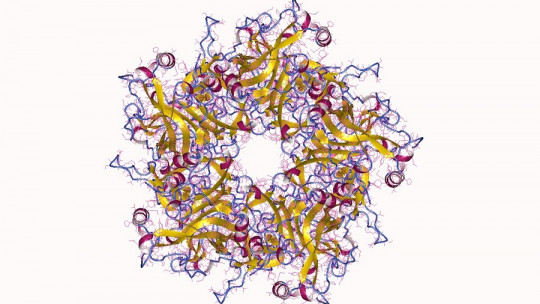

In essence, it is about replicating the genetic material of the virus, that its genetic message is transcribed into an RNA molecule and this is translated into the production of viral proteins, both those that form the capsid and the enzymatic proteins inside. In this phase, different types of viruses must be taken into account, since DNA is not always found in their capsid.

Viruses with DNA, which conform to the process explained in the previous phase, replicate their genetic material in a similar way to how cells do, using the cell’s DNA as a scaffold to multiply that material.

Other viruses, which contain RNA, replicate their genetic material without needing to resort to cellular DNA Each RNA strand works on its own as a template for the synthesis of its complementary ones, with the cell being a simple environment in which the process takes place.

However new strands of DNA and RNA are formed, the assembly of the pieces then takes place to build the new virions. This assembly can occur through the action of enzymes or mechanically.

5. Release of new viruses

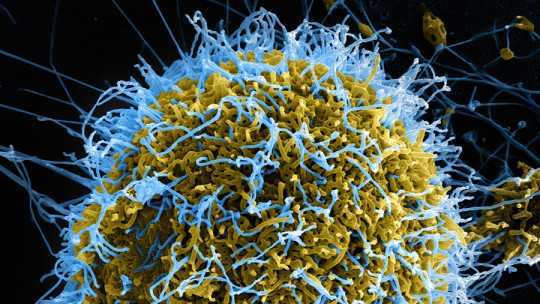

After the multiplication of the viruses has occurred, the release of new individuals takes place, which, like their ‘parent’, will have the capacity to infect other host cells.

On the one hand there is the budding release This occurs when the new viruses do not wait for the cell to die before abandoning it, but leave it at the same time as they reproduce, so that the cell remains alive while ‘giving birth’ to new viruses.

An example of a virus that is released by budding is influenza A. At the time the virus is released, it acquires the lipid envelope of the host cell.

On the other hand we have release by lysis, in which the death of the cell that has been infected does occur. Viruses that reproduce with this modality are called cytolytic, since they kill the cell when infecting it. An example of these is the smallpox virus.

Once the newly generated virus leaves the cell, some of its proteins remain on the host cell membrane. These will serve as potential targets for nearby antibodies.

The residual viral proteins that remain in the cytoplasm can be processed by the cell itself, if it is still alive, and presented on its surface along with MHC (major histocompatibility complex) molecules, recognized by T cells.