The Baroque is an era and an artistic movement that occurred, mainly, in the 17th century. This artistic style has numerous masterpieces, distributed among the best museums in the world.

In this article We will focus on baroque painting and rescue 10 of its most important paintings

Baroque painting

The 17th century witnessed the emergence of authentic masters of painting. Artists such as Velázquez, Vermeer, Rubens and Ribera filled the pages of art history with numerous masterpieces, essential to understand both this historical period and the evolution of art in general.

As with most artistic movements, the Baroque is not a single style In each region and each country it had its own characteristics, driven by its own economic, religious and social context. Thus, while in Catholic countries this style served as a vehicle for the Counter-Reformation, in Protestant regions it became much more intimate and personal, as it was promoted by the merchants and bourgeoisie of the cities.

The 10 main paintings of the Baroque

Next, we will take a short trip through the 10 most important Baroque paintings.

1. Las Meninasby Diego Velázquez (Prado Museum, Madrid)

It is probably one of the most reproduced pictorial works and has the greatest fame throughout the world. The canvas is known as Las Meninasalthough its original name was The family of Philip IV. It is, without a doubt, one of the masterpieces of baroque painting and art history in general

It was painted in 1656 in the Prince’s Room of the Alcázar of Madrid, and it recreates an amazing play of lights and perspective. In the background, reflected in a mirror, we see the busts of the monarchs, King Philip IV and his wife Mariana of Austria. To the left of the canvas, Velázquez takes a self-portrait at the easel. Interpretations of the work have been and continue to be very varied. He is painting the kings, and suddenly he is interrupted by the little Infanta Margarita, who is accompanied by her meninas and her entourage? Be that as it may, the painting fully immerses the viewer in the scene, as if he were another character in it.

2. Judith and Holofernesby Artemisia Gentileschi (Uffizi Gallery, Florence)

For some years now, the extraordinary work of Artemisia Gentileschi has been recovering the place it deserves in the history of painting. Judith and Holofernes is one of her masterpieces not only of her pictorial corpus, but of baroque painting in general.

The artist represents us the moment, recorded in the Bible, in which Judith, the Jewish heroine, beheads Holofernes, a Babylonian general who is after her Artemisia represents the moment with a ferocity that freezes your breath. Many critics have wanted to see in the rawness of this painting all the rage and suffering that the rape of which she was a victim entailed for the painter shortly before the execution of the first version of the painting, preserved in the Capodimonte Museum, Naples. In any case, the wonderful chiaroscuro, the composition and the dynamism of the characters make this work one of the best examples of Baroque painting.

3. Girl reading a letter in front of the open windowby Johannes Vermeer (Alte Meister, Dresden)

Vermeer’s great and, at the same time, intimate pictorial universe is unfortunately reduced to around thirty recognized works. This scarcity of artistic production turns this Dutch Baroque artist into a painter surrounded by a halo of mystery. His interiors were highly prized at the time, although they later fell into oblivion and were not claimed until much later by the 19th-century Impressionists.

The work at hand perfectly represents that universe of domestic intimacy characteristic of the painter In a room illuminated by the milky light that enters through an open window, a young woman is concentrated on reading a letter. Her private world becomes more inaccessible because we cannot physically reach her, since the table and the curtain in the foreground prevent us from doing so. This canvas is a beautiful example of baroque painting from the Netherlands and, above all, of that world of elusive and almost ghostly characters that populate the work of this extraordinary artist.

4. Still lifeby Clara Peeters (Prado Museum, Madrid)

The genre of still lifes has not been very well considered in the history of art, despite the fact that it is a genre that requires great detail and, of course, an indisputable ability to capture textures and surfaces. A masterpiece of the genre is, without a doubt, this Still life by the painter Clara Peeters.

In it, the artist’s virtuosity is not only evident in the careful representation of the elements, but also in the series of self-portraits that the painter made, as a reflection, in the jug and in the glass. Capturing a reflection on a surface was something that required exquisite virtuosity, and Clara demonstrates her pictorial ability through this resource, in addition to being a way to reclaim her role as an artist in a male-dominated profession

5. The disbelief of Saint Thomasby Caravaggio (Schloss Sanssouci, Potsdam)

The biblical theme of the saint’s doubt before the resurrection of Christ is captured in this work with impressive naturalism. Saint Thomas is inserting a finger into the wound that Jesus shows on one of his sides Christ himself guides his hand, encouraging him to believe through physical evidence what he has not believed through faith. This scene has never been seen told with so much, we could say, rawness. Caravaggio’s characteristic realism is evident in the anatomy of the bodies, in the wrinkles that furrow the foreheads of the apostles, in the dirty nails that Saint Thomas himself has and, above all, in the tip of his finger entering the flesh of Christ. Caravaggio’s work is one of the best examples that the Baroque is not only theatricality and pageantry, but often also approaches reality with surprising naturalism.

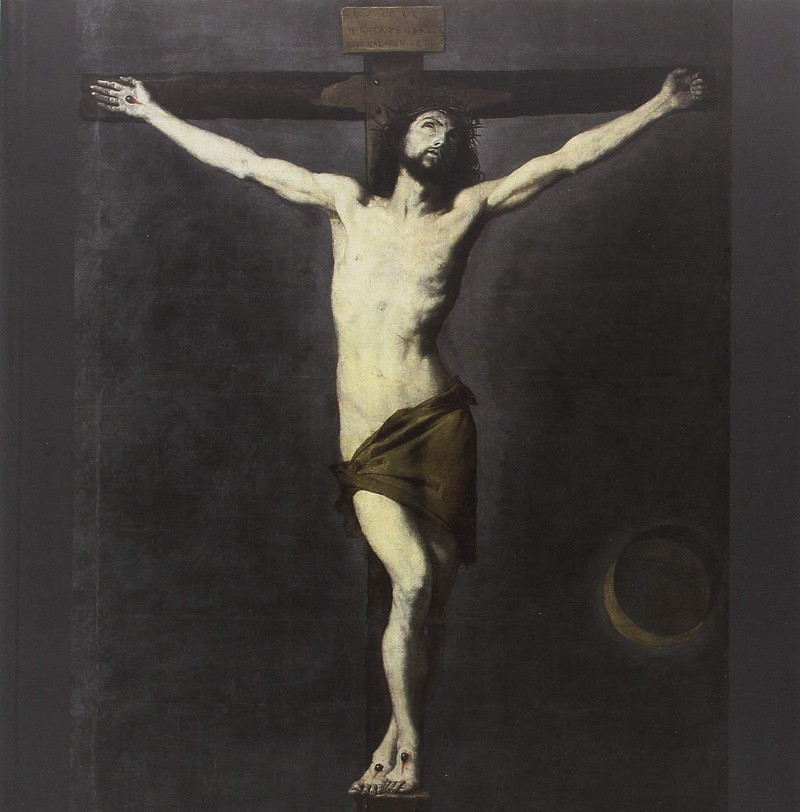

6. Crucified Christby José de Ribera (Diocesan Museum of Sacred Art, Vitoria-Gasteiz)

One of the most impressive crucified figures in baroque painting It is preserved in the Diocesan Museum of Sacred Art of Vitoria-Gasteiz, from the disappeared convent of Santo Domingo, and is considered one of the best representations of the crucified Christ in Spanish painting. Against a neutral and markedly dark background, which reinforces the idea of the biblical eclipse that accompanied the death of Christ, the figure of Jesus stands on the cross, with his body white and contorted in a forced contrapposto. The only source of light is his body, since even the purity cloth is of a similar color to the wood of the cross to which it is nailed. The scene seems to capture the moment when Christ raises his eyes towards heaven and murmurs: “It is all over. Consumatum is”.

7. Children eating grapes and melonby Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (Alte Pinakothek, Munich)

We have already commented that realism is also typical of Baroque art. A good example of this is this wonderful canvas by the painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, preserved in Munich, which represents two poorly dressed children eating grapes and melon. Spain in the 17th century offered stark contrasts, and poverty was a common sight on the streets of cities like Madrid. On this occasion, Murillo represents the two boys concentrated on their food. They are not looking at the viewer; In fact, they barely notice our presence. While they devour the melon and grapes (perhaps one of the few foods they will have access to for many days), they talk calmly, as witnessed by their exchanged glances. The bare, dirty feet and the worn clothes add a dramatic note to the endearing scene.

8. Vault with Apotheosis of the Spanish monarchyby Luca Giordano (Prado Museum, Madrid)

This fantastic ceiling, made at the end of the 17th century using the false fresco technique, can currently be seen in the Prado Museum Library in Madrid. Originally the vault belonged to the old Hall of Ambassadors of the Buen Retiro Palace a place of rest and leisure that the Count-Duke of Olivares ordered to be built for King Felipe IV.

As its name indicates, the Hall of Ambassadors was the reception place for the monarch, so the iconography displayed on its ceiling is an exaltation of the Hispanic monarchy. Giordano created an extraordinary composition, dotted with allegories and symbols taken from mythology that sought to highlight the antiquity of the Spanish crown and its preeminence over other European royal houses.

9. The three gracesby Rubens (Prado Museum, Madrid)

Rubens apparently created this canvas, one of the most famous of his works, for his own enjoyment, as demonstrated by the fact that, upon his death, it was among his personal collection. In fact, the features of the woman on the left are very similar to those of his second wife, Helena Fourment, whom Rubens married when she was only sixteen years old and he was fifty-three. Since ancient times, It is common to find the reason for the Graces related to betrothal, so it does not seem unreasonable to assume that the artist painted the painting as a tribute to his own marriage. The three figures rise voluptuously and join their hands in what appears to be a kind of dance. It is, indeed, one of the artist’s most elegant and sensual paintings.

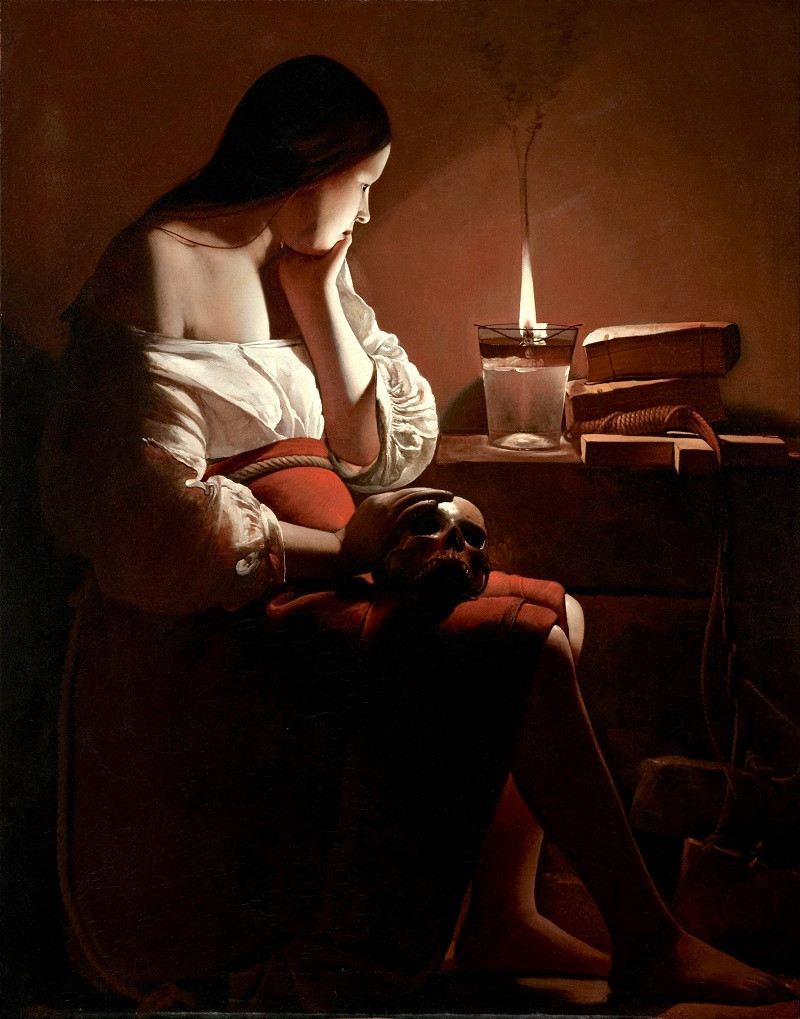

10. Penitent Magdalena of the lampby Georges de La Tour (Louvre Museum, Paris)

De La Tour is a fantastic painter who is famous for the exquisite chiaroscuro of his compositions, achieved through the glow of one or several candles.

In this case, the painting shows us a Mary Magdalene absorbed in her meditation Her gaze is fixed on the fire of the candle that burns before her, the only focus of light in the painting, as is usual in the artist’s work. The saint rests her head in one hand, while in the other, which rests on her lap, she holds a skull, a symbol of penitence and the transience of life, so typical of the Baroque. The motif of the penitent Magdalene was very common in the 17th century. De La Tour himself made up to five versions of this painting. In two of them, the skull is on the table, and with its volume hides the candle fire, which further highlights the chiaroscuro of the scene.