Vere Gordon Childe was an Australian archaeologist who helped archeology be taken seriously as an independent science instead of being seen as a mere ancillary science.

His works helped to understand the cultural evolution of prehistoric human beings, in addition to contributing to the idea that it is through the contact of different peoples, breaking their isolationism, that progress is generated.

Next we are going to learn about the life of this researcher through a biography of Vere Gordon Childe

Brief biography of Vere Gordon Childe

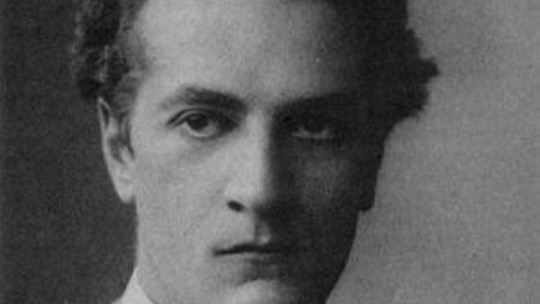

Gordon Vere Childe was born in Sydney, Colony of New South Wales, Australia, on April 14, 1892 He was the son of middle-class English immigrants. He spent his childhood living in the oceanic country, studying there and graduating from the university in his hometown.

He then moved to Oxford, England, where he initially became interested in classical philology studies. However, Gordon Childe He chose to change fields under the influence of professors Arthur Evans and J. Myres, finally opting for prehistoric archeology

As a student, he was active in the Oxford Fabian Society and openly opposed the First World War.

Round trip to Australia

Once he finished his studies in England, he returned to his native Australia. He joined the Australian Union of Democratic Control, which managed to reject compulsory military service. He became personal secretary to the Labor governor of New South Wales but left in 1921, deeply disenchanted with politics, he would return to Europe. From his raw experience with the governor he would write a book “How Labor Governs”

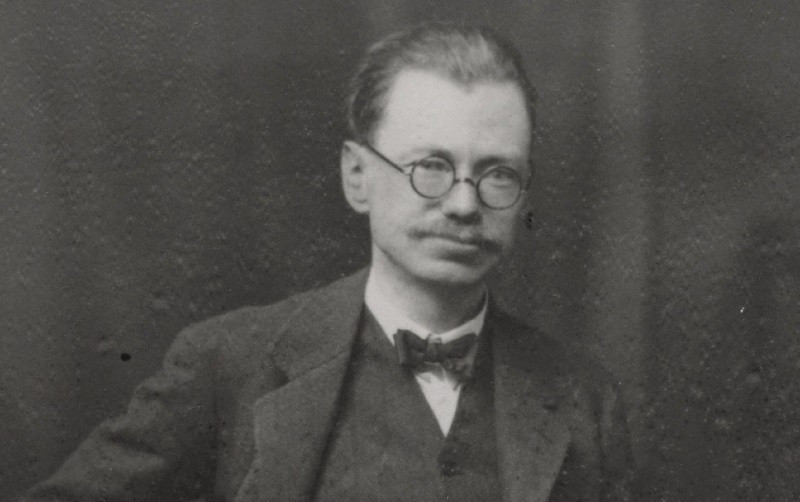

Vere Gordon Childe made a trip to central and eastern Europe to see first-hand the archaeological remains found there. He would return to Britain, where he held various jobs, including librarian of the Royal Anthropological Institute until in 1925 he published “The Dawn of European Civilization.”

Thanks to the success he obtained with this work The University of Edinburgh offered Childe the newly created chair of archeology which allowed him to be one of the first professional archaeologists of his time.

Years of popularity

In the following years he published more works, both specialized and for the general public, all of them giving him international fame.

His most notable specialized publications are “The Dawn of European Civilization”, “The Danube in Prehistory” (The Danube in prehistory, 1929) and “The Bronze Age” (The Bronze Age, 1930).

His books for laymen, marked by his interest in cultural evolution, include “What Happened in History” (1942), in which he synthesizes his vision of history and culture.

These works made the figure of Vere Gordon Childe someone very recognized before he reached 40 years of age His great field work and literary production earned him the fame of one of the most renowned archaeologists of his time.

End of your life

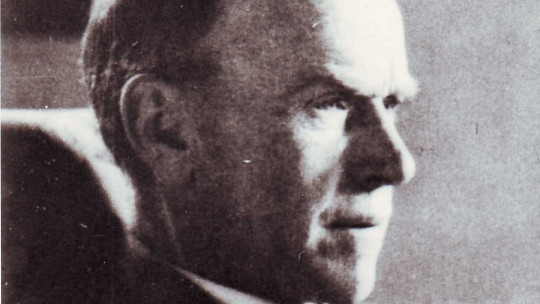

After a stay in Edinburgh in 1945, he moved to London to teach at its University, while also directing the Institute of Archaeology. During his last years his literary production focused on the study of work methods in archeology aiming to renew this discipline.

His ideas regarding this task were collected in his posthumous work “The Prehistory of European Society”, 1958. In 1956 he returned to his native Australia, dying the following year.

The circumstances of his death are considered extremely strange Childe is said to have believed that the best time for life to end is when one is happy and strong, which, coupled with an almost pathological fear of old age, is said to have been his intention for this to be the case with his life by his own hand. .

On October 19, 1957, Childe left for an area in Govett’s Leap, in the Australian Blue Mountains where he had grown up. He climbed a mountain, left his hat, glasses, compass, pipe and a raincoat on the top and fell to his death from a height of 300 meters. He was 65 years old.

The official report of the time indicated that his death was accidental, although acquaintances revealed that, judging by the content of some letters left by Childe himself before the tragic event, this incident had been entirely his decision.

The thought of Vere G. Childe

Gordon Childe’s thinking can be approached from two angles. One is from his ideas about archeology, which changed the mentality of this discipline, and the other is from his conception of history and its evolution. These points are strongly intertwined in Childe’s literary production. Nor can one separate his work from the Marxist ideology that he maintained and which is evident in his theses on the progress of human beings and the importance given to social and economic aspects.

Childe tried to stop archeology from being seen as a mere auxiliary science, an idea widely accepted in his time. For him, the information revealed by archeology constituted a historical document of great importance, far superior to that available in the written texts of treaties, books and other documents from past times. The method of extraction of archaeological remains, together with the interpretation of what they were used for and what they say about the people who used them, constitute the fundamental pillar of archaeology, a pure science.

Gordon Childe is considered a diffusionist It defines a culture as certain types of remains, such as pots, ornaments, funerary remains… that repeatedly appear together. The changes in these cultures throughout history would correspond to ethnic modifications due to migratory movements, invasions or as a consequence of the dissemination of an object or idea. Childe’s method was to seek to reconstruct prehistory by chronologically ordering the sets of objects that were exponents of these movements or that exerted influences among peoples in one way or another.

With the rise of Hitler in Germany and the spread of Nazi theses, Vere Gordon Childe was very concerned about the possibility that his ethnographic and archaeological theories would be misinterpreted. Childe denied that his concept of the people had racial implications and defended the idea that cultural progress is achieved by breaking the isolation of human groups, getting them to share their ideas. He considered it important to study the common heritage of humanity.

He dedicated several works, both academic and popular, to refuting the ethnic archeology of Gustaf Kossinna, highly supported by the Nazis, who proposed that it was possible to trace the origin of races to their prehistoric roots and relate it to the degree of progress achieved. Naturally, those who shared these Nazi theses defended that the white Aryan race was the one that historically had given the most evidence of the capacity for progress and development.

Childe’s concern about Nazism and its pseudoscience led him to present his idea of history from a Marxist perspective in two books : “The origins of civilization” and “What happened in history?” In them he reflects on the progress of human beings. After analyzing the first peoples and the organization of ancient civilizations, he concluded that the main brake factor in technological and cultural development in a society is the ruling class. The elites, in order to prevent them from losing their privileges and changing their social status with the change in society, contain social transformations.

However, this strategy of the ruling class increases the costs of maintaining the State and, also due to the growing concentration of wealth in the hands of the leaders, will damage the economy until civilization collapses. But this decline of a society does not necessarily imply something negative, but rather it can be an opportunity to reorganize the economy and put wealth and ideas into circulation again.

Gordon Childe is credited with being the first to propose a socioeconomic interpretation of primitive European societies and to be the leading Marxist archaeologist in the West. In addition, he contributed concepts as distinctive today as the “Neolithic revolution,” a change in human history in which our species intelligently used cultivation and domestication to survive and prosper. Today, this concept has become essential to talk about the origins of agriculture, a key milestone for the human species to reach what it is today.