Although in the 1930s it was already suspected that chromosomes housed genes, the pieces of genetic material that encode who we are, this was not empirically proven. Many had tried, but no one had found visual proof of the chromosome-gene relationship.

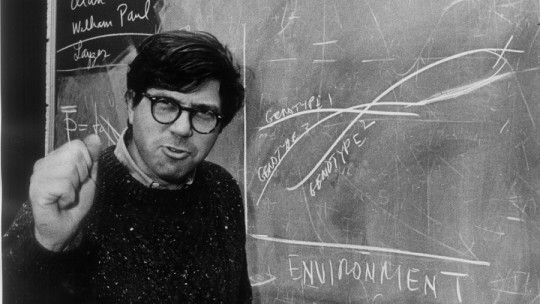

But Barbara McClintock arrived, who with her corn plants grown by herself, would be able to prove it, despite the fact that many saw her as a mere botanist with the air of a geneticist.

The figure of this researcher is that of a person who, due to how advanced she was for her time, was misunderstood. Next we will discover what her story was through a biography of Barbara McClintock in which we will see why it has been so important for the history of genetics.

Brief Biography of Barbara McClintock

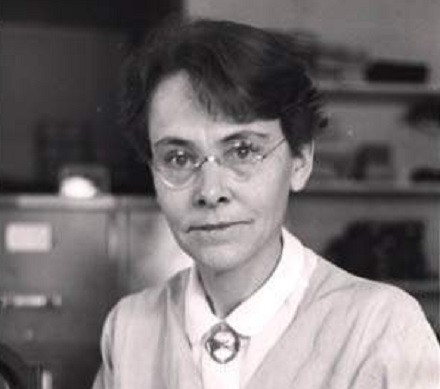

Barbara McClintock was an American scientist specialized in cytogenetics who won the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology in 1983 being the seventh woman to receive such recognition.

His work precisely answered the most interesting question of the 1930s: in what structure of the cell are genes found? McClintock’s research, together with his doctoral student Harriet Creighton, served to empirically demonstrate that genes were located on chromosomes. His work with corn plants provided for the first time a visual connection between certain hereditary traits and their basis in chromosomes

Their research also discovered that genes do not always occupy the same place on the chromosome. McClintock discovered the transposition of genes, something that conflicted with the idea of his time that genetic material was static. It was, therefore, a much more complex and flexible element than was assumed at the time, a dynamic structure capable of reorganizing itself.

Childhood and adolescence

Barbara McClintock was born in Hartford, Connecticut (United States) on June 16, 1902 She was initially registered as Eleanor, but she changed the registration four months later to the name by which she was known, Barbara. She was the third child of the doctor Thomas Henry McClintock and Sara Handy McClintock. She showed greater closeness to her father than to her mother and, in her adulthood, she highlighted that they had both been very supportive of her, although her relations with her mother had been rather cold.

Even as a child, McClintock showed great independence, something that she herself would describe as a great ability to be alone. From the time she was three years old until she started going to school, McClintock lived with her aunt and uncle in the neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, in order to help her family financially while her father established a business. consulting room.

He finished his secondary education at Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn. From a young age he showed interest in science, so he decided to continue his studies at Cornell University. His mother was opposed to this, not wanting her daughters to receive higher education, believing that this would harm their chances of getting married. Added to this, the family was going through certain financial problems that prevented them from paying for his children’s university studies.

Fortunately, Barbara McClintock was able to attend the Cornell Agricultural School without having to pay tuition and, after completing her secondary education, she was able to combine her work in an employment office with self-study training derived from going to the public library. Finally, and thanks to the intervention of her father, she began to attend Cornell in 1919 where her success would not only be academic but also social, with her being elected president of a student association in her first year.

Training and research at Cornell

McClintock began studying at the Cornell Agricultural School in 1919, where he would study botany and obtain his Bachelor of Science (BSc) degree in 1923. His interest in genetics was awakened in 1921, while he was attending the first course in that subject, directed by the plant breeder and geneticist CB Hutchison. Due to McClintock’s great interest, Hutchinson invited her to participate in a graduate genetics course in 1922. This would mark a before and after in McClintock’s career, focusing her vital efforts on delving deeper into genetics.

Both while studying her degree and already working as a botany professor, McClintock He dedicated himself to what was then a novel field of corn cytogenetics His research group consisted of plant breeders and cytologists, including Charles R. Burnham, Marcus Rhoades, George Wells Beadle, and Harriet Creighton.

The main objective of McClintock’s work at that time was to develop techniques to visualize and characterize maize chromosomes. He created a technique based on carmine staining to be able to see these chromosomes using optical microscopy, showing for the first time the shape of the ten chromosomes of corn. By studying the morphology of these chromosomes, he was able to relate co-inherited characters to chromosomal segments and confirm that the chromosomes were the home of the genes.

In 1930, Barbara McClintock He was the first person to describe the crossing over that occurs between homologous chromosomes during meiosis Together with her doctoral thesis student, Harriet Creighton, in 1931 he demonstrated that there is a relationship between this meiotic chromosome crossing over and the recombination of heritable characters. McClintock and Creighton observed that chromosome recombination and the resulting phenotype resulted in the inheritance of a new trait.

During the summers of 1931 and 1932 he worked in Missouri with the prestigious geneticist Lewis Stadler, who showed him the use of X-rays as an element capable of inducing mutations. Using mutagenized corn lines, McClintock identified ring chromosomes, that is, circular DNA structures generated by the fusion of the ends into a single irradiated chromosome. During this period he also demonstrated the existence of the nucleolar organizer in a region of maize chromosome 6, which has been shown to be essential for nucleolus assembly.

Barbara McClintock obtained a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship that paid for six months of apprenticeship in Germany during 1933 and 1934. Her initial plan was to work with geneticist Curt Stern, a researcher who demonstrated interbreeding in Drosophila (flies) weeks after she and Creighton did the same with corn, but it so happened that Stern emigrated to the United States right at that same time. For this reason, the laboratory that finally accepted McClintock was that of Richard B. Goldschmidt.

Due to the political tension in Germany at the time, which saw the rise of the Nazis imminent, McClintock returned to Cornell where she would remain until 1936. That year she obtained the position of assistant professor in the Department of Botany at the University of Missouri-Columbia.

Missouri Experiences

While at the University of Missouri, McClintock continued the line of mutagenesis using X-rays. He observed that chromosomes broke and fused under these conditions, but that the endosperm cells also did so spontaneously. He discovered how The ends of the broken chromatids were joined together after DNA replication in the phase of mitosis

Specifically, it was in anaphase that the broken chromosomes formed a chromatid bridge, which disappeared when the chromatids moved towards the cell poles. These breaks disappeared, forming unions during the interphase of the next mitosis, repeating the cycle and causing massive mutations, which led to the appearance of variegated endosperm.

This cycle of chromosome breakage, fusion, and bridging was considered a crucial discovery at the time First, because he showed that chromosome joining was not a random process, and second, because he identified a mechanism for the production of large-scale mutations. In fact, this finding is so important that it is still used today, especially in the study of cancer research.

Although her research was producing very green shoots in Missouri, McClintock was not at all satisfied with her position. She felt excluded from faculty meetings and was not notified of vacancies at other institutions Although she had initially had a lot of support from her classmates, the academic competitiveness and the fact that she was an independent and solitary woman caused her to become increasingly alienated from her research. .

An unpleasant anecdote that would demonstrate how little she was valued by some of her colleagues is that in 1936 an engagement announcement for a woman with the same name and surname appeared in the newspapers. Mistaking this woman for her, her department head threatened to fire her if he married her. At that time McClintock was already vice president of the Genetics Society of the United States.

McClintock had lost confidence in his coordinator Stadler and the University of Missouri administration. Therefore, when in 1941 he received an invitation from the director of the Genetics Department at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory to spend the summer there, he immediately accepted it. He did it as a way to look for a job somewhere other than Missouri, trying his luck.

Also around this time he would accept a visiting professorship at Columbia University, where his colleague Marcus Rhoades was a professor. He offered to share his line of research with Long Island’s Cold Spring Harbor. In December 1941 he was offered a research position at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, part of the Department of Genetics at the Carnegie Institution of Washington She would end up accepting it.

Investigations at Cold Spring Harbor

After a year working part-time at Cold Spring Harbor, Barbara McClintock accepted a full-time research position there. There she would continue her work on the rupture-merger-bridge cycle, being an extraordinarily productive period in scientific publications.

Because of this prolific research, McClintock She was recognized in 1944 as an academic in the United States National Academy of Sciences, being the third woman to be elected A year later she was named president of the Genetics Society of America, an honor that had never been given to a woman.

On the recommendation of geneticist George Beadle, in 1944 he did a cytogenetic analysis on the fungus Neurospora crassa. Working with this fungus, Beadle had demonstrated a gene-enzyme relationship for the first time. McClintock determined the karyotype of the fungus as well as its life cycle and, since then, N. crassa has been used as a model organism in genetic studies.

- You may be interested: “Differences between mitosis and meiosis”

Discovery of gene regulation

McClintock He dedicated the summer of 1944 to figuring out the biological mechanism behind the genetic mosaic phenomenon, a genetic condition that caused the seeds of the same ear of corn to have different colors. He found two places on the chromosomes (loci) that he called “Dissociator” (Ds) and “Activator” (Ac). Ds was related to chromosome breakage, in addition to affecting the activity of nearby genes when Ac was present. In 1948 he discovered that both loci were transposable elements that could change their place on the chromosome.

McClintock studied the effects of transposition of Ac and Ds analyzing the coloring patterns in corn nuclei throughout generations of crosses. His observations led him to conclude that Ac controlled the transposition of Ds on chromosome 9, and that its transposition was the cause of chromosome breakage.

When Ds moves, the gene that determines the color of the aleurone (corn seed) is expressed, since the repressive effect of Ds is lost and, consequently, the appearance of color occurs. This transposition is random, which means that it will not affect all the cells, which explains why mosaic occurs in the infructescence. McClintock also determined that the rearrangement of Ds is determined by the copy number of Ac.

During the 50’s developed a hypothesis that explained how transposable elements regulate the action of genes, inhibiting or modulating them He defined Ds and Ac as control units or regulatory elements, to clearly separate them from genes. With this, he hypothesized that gene regulation can explain how multicellular organisms can diversify the characteristics of each cell, despite their genome being identical. This idea completely changed the concept of the genome, which until then was interpreted as a mere set of static instructions.

McClintock’s work on gene regulation and control elements was so complex and novel that The rest of the scientific community was somewhat suspicious of his discoveries In fact, she herself described that response as a mixture of perplexity and hostility. Despite this, McClintock moved forward and continued with her line of research.

Later he would identify a new regulatory element called “Suppressor-mutator” (Spm) that, although similar to Ac and Ds, carried out more complex functions. However, given the reactions of the scientific community at the time and McClintock’s perception that he was moving away from the scientific mainstream, he had him stop publishing his results.

Recognitions and recent years

In 1967 McClintock retired from his position at the Carnegie Institution, being named a distinguished member of it. This distinction allowed her to continue working as a scientist emeritus at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory with her graduate student colleagues. In fact, she remained affiliated with the laboratory until the day of her death.

In 1973 he would confess the reason why he decided not to continue publishing his findings on the regulatory elements, despite continuing to investigate on his own. He commented that, because of his experience in laboratories, it is very difficult to make another person aware of his tacit assumptions. He considered that, due to the fixed ideas of many scientists, some advances cannot be shared at a given time, as they will be guaranteed criticism. You must wait for a conceptual change to occur and communicate it at the right time.

His experience gave strength to his opinions in this regard, Well, it took decades for their findings to be taken into account Barbara McClintock’s work was only fully appreciated when, in the 1960s, geneticists François Jacob and Jacques Monod reached similar conclusions with their respective studies, presented in a 1961 work entitled “Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins.” ” (“Genetic mechanisms regulating protein synthesis”). McClintock read the work and compared her findings with those put forward by the French.

Fortunately, McClintock was eventually widely recognized for her work His discovery of transposition was valued when this same process was described by other authors in bacteria and yeast in the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1970s, Ac and Ds were cloned, showing that they were class II transposons.

Ac is a complete transposon, which encodes a functional transposase in its sequence, allowing the movement of the element through the genome. Instead, Ds encodes a mutated, non-functional version of the transposase and requires the presence of Ac in order to jump in the genome, something that fits with McClintock’s functional description. Later studies demonstrated that these sequences do not move if they do not suffer stress, such as rupture by irradiation or others, for this reason their activation could provide an evolutionary source of variability.

McClintock He understood the role of these agents as evolutionary agents before other scientists even suspected it In fact, today the Ac/Ds system is used as a mutagenesis tool in plants, to characterize genes of unknown function and in species other than maize.

Thanks to the fact that the truth of her findings and the value of her work, applicable beyond the field of botany, was finally recognized, Barbara McClintock received the Nobel Prize in Physiology in 1983, being the seventh woman to achieve it and, unlike others Occasionally, only one person receives it. Normally, the Nobel Prize in science is won by research teams, but since McClintock had to work on her own for most of her life, the credit was hers alone.

Barbara McClintock died of natural causes on September 2, 1992 at Huntington Hospital, near the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory where she lived so many moments. She was ninety years old, and she died without leaving children or having ever married?