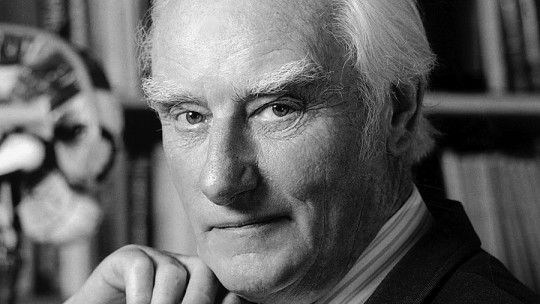

James Dewey Watson and Francis Crick are two very important figures in the history of biology with their discovery of what DNA is like. Thanks to their discoveries, in 1962 they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, but they were joined by a third name: Maurice Wilkins.

Wilkins contributed to the discovery of what DNA was like, something that has undoubtedly contributed to the progress of humanity but also caused him to become involved in a controversy with researcher Rosalind Franklin.

Next we will read about the life of this researcher through a biography of Maurice Wilkins seeing how his professional career developed and how the controversy over the structure of DNA arose.

Brief Biography of Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins

Maurice Wilkins was a British biophysicist who received the Nobel Prize for his research in the areas of physics and biophysics contributing to a better scientific understanding of aspects such as phosphorescence, isotope separation, optical microscopy and X-ray diffraction and the development of radar.

He is best known for having worked at King’s College London, getting involved in research into the structure of DNA, which also brought him some controversy with one of the most notable female researchers of the last century, Rosalind Franklin.

Early years and education

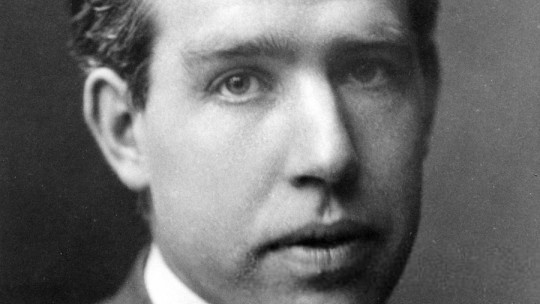

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins He was born on December 15, 1916 in Pongaroa, New Zealand, into a family of Irish origin His father was Edgar Henry Wilkins, a physician. His family came from Dublin, where his paternal grandfather had been the headmaster of the local high school and his maternal grandfather had been chief of police.

When Maurice was 6 years old, he and his family moved to Birmingham, England, and from 1929 to 1934 he attended Wylde Green College. After passing through this educational institution, Wilkins studied at King Edward’s School, also in Birmingham.

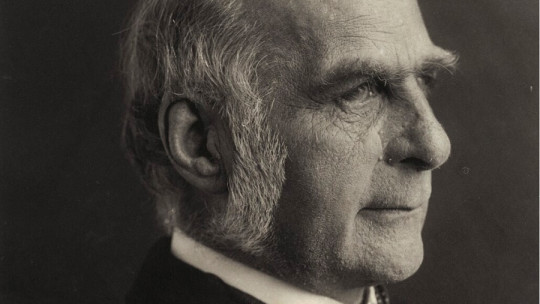

The young Maurice attended St John’s College, Cambridge in 1935, later specializing in physics He would also receive a Bachelor of Arts in 1938. Mark Oliphan, who was one of Wilkins’s professors at St. John’s, had been appointed to the Chair of Physics at the University of Birmingham, and had named John Randall as one of the companions of his. Randall would end up being Wilkins’ tutor for his doctoral thesis.

In 1945, Randall and Wilkins published four papers for the Proceedings of the Royal Society on phosphorescence and electrons. Wilkins received his doctorate for his work in 1940.

Second World War and postwar

Throughout World War II Wilkins developed and improved radar displays in Birmingham, and later worked on isotope separation on the Manhattan Project at the University of California, Berkeley, during the years 1944 and 1945.

Meanwhile, Randall had been awarded a Professorship in Physics at the University of St. Andrews. In 1945, he asked Wilkins to come to this university to work as an assistant lecturer.

Randall was negotiating with the British Medical Research Council (MRC) to open a laboratory in which to apply physics research methodology to the field of biology. As surprising as it may seem from a current perspective, the truth is that in the 1940s, combining these two disciplines was extremely novel and even unthinkable. Biophysics had barely made a show of presence in the scientific world and there was a certain reactance to investing in it.

The MRC told Randall that to open such a laboratory it was necessary to do so at another university. In 1946 Randall was appointed Professor of Physics in charge of the physics department at King’s College, with sufficient funding to open a Biophysics Unit, where he made Maurice Wilkins his assistant head. So that They managed to create a team of scientists specialized in both physics and biological sciences His philosophy was to explore the use of as many techniques as possible in parallel, see which ones were the most promising, and focus on them.

First phase of DNA study

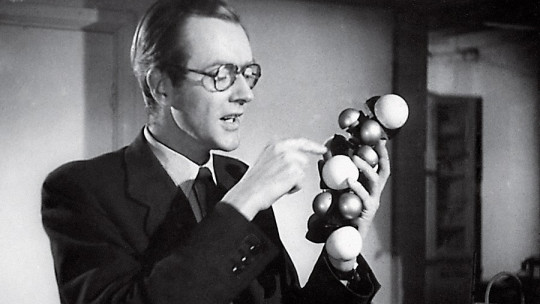

At King’s College, Wilkins devoted himself, among other things, to the diffraction of X-rays in the sperm of sheep and to the study of the findings made by the Swiss scientist Rudolf Signer extracting DNA from the thymus of the calf. Wilkins discovered that it was possible to produce thin threads from a concentrated DNA solution containing highly ordered DNA arrays

Using selected bundles of these DNA strands and keeping them hydrated, Wilkins and his graduate student Raymond Gosling obtained X-ray photographs of DNA that showed a long molecule of this substance. These works with to Francis Crick.

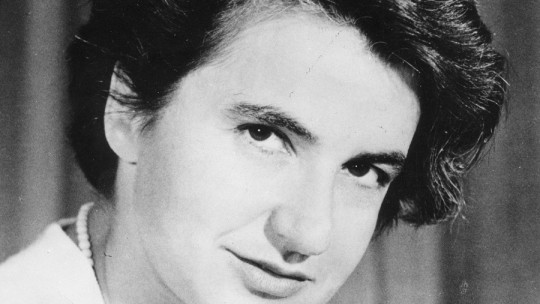

Wilkins knew that experiments on the purified DNA strands would require better X-ray equipment and, for this reason, he ordered a new X-ray tube and a new microcamera. Also He suggested that Randall recommend Rosalind Franklin, who was doing research in Paris at the time, to devote herself to the study of DNA instead of proteins.

Second phase of DNA study

At the beginning of 1951, Franklin finally arrived in the United Kingdom. Wilkins was on vacation and missed the initial meeting in which Raymond Gosling represented him before Alex Stoles who, like Crick, would discover the mathematical foundations that explained how helical structures diffracted X-rays.

There hadn’t been much DNA research done in recent months, and the new x-ray tube was sitting idle, waiting for Franklin to get his hands on it. Franklin ended up studying DNA, Gosling became her PhD student, and she hoped that X-ray DNA diffraction would be her project However, Wilkins returned to the laboratory hoping, on the one hand, that Franklin would be his collaborator and that they would work together on the DNA project that he had started.

The confusion over what Franklin’s and Wilkins’ roles were in relation to this project, which would later spark tensions between the two researchers, is attributable to Randall. Randall sent a letter indicating to Rosalind Franklin that she and Gosling were going to be the only ones in charge of the DNA study, but he did not notify Wilkins of her decision and Maurice learned of the contents of the letter years after Franklin’s death.

The tension was due to Randall making Rosalind believe that Wilkins and Stokes wanted to stop working on the DNA project and that therefore it was Rosalind’s job from that moment on. As Wilkins continued to study DNA, Franklin interpreted it as an intrusion into his new field of study further aggravating the conflict.

In November 1951, Wilkins obtained evidence that DNA in cells and purified DNA show a helical structure Maurice Wilkins met with Watson and Crick and kept them informed of his results. This information from Wilkins, along with additional data from Franklin’s research, spurred Watson and Crick to create their first molecular model of DNA, a model with phosphate as the “backbone” of the molecule in the center.

At the beginning of 1952 Wilkins began a series of experiments with cuttlefish sperm. At that same time, Franklin resigned from the DNA molecular modeling efforts and continued his work on detailed analysis of his X-ray diffraction data

In the spring of that same year, Franklin obtained permission from Randall to move his collaborative fellowship from King’s College to John Bernal’s laboratory at Birbeck College, also in London. Franklin would remain at King’s College until mid-March 1953.

In early 1953, Watson visited King’s College where Wilkins showed him a high-quality image of the B form of DNA under X-ray diffraction, now known as “photograph 51.” The photo was not his work, but rather Rosalind Franklin’s, who had taken it in March 1952. Wilkins showed this photograph without notifying its author or requesting her permission.

Knowing that Linus Pauling was working on DNA as well and had proposed a model of DNA for publication, Watson and Crick worked even harder to deduce what the structure of DNA was. Crick gained access to information obtained from Franklin regarding DNA. With this information, Watson and Crick published their proposal for DNA with a double helical structure in an article in Nature magazine in April 1953 in which they acknowledged having been stimulated by the unpublished results of both Wilkins and Franklin.

Following the 1953 papers on the double helix structure, Wilkins continued research to establish the helical model as valid across different biological species as well as living systems. He became MRC deputy director of the Biophysics Unit at King’s College in 1955, and succeeded Randall as director of the unit from 1970 to 1972.

Personal life

Wilkins was married twice. His first wife, Ruth, was an art student he met when he went to Berkeley. They ended up divorcing and Ruth had Wilkins’ son after the divorce. Maurice Wilkins subsequently married his second wife, Patricia Ann Chidgey in 1959. With her he had four children: Sarah, George, Emily and William.

Maurice Wilkins’ political views brought him some trouble in his youth, in the years before World War II. Wilkins was a pacifist activist, and in fact joined the British Anti-War Scientists Group. He was also a member of the Communist Party, although the Soviet Union’s invasion of Poland in September 1939 changed his mind.

Due to his communist ideas, Wilkins He was on the list of potential suspects for revealing atomic secrets of British intelligence to the USSR The documents confirming this were revealed to the public in August 2010, showing that there was a surveillance device that ended in 1953.

He died on October 5, 2004, in London, England, at the age of 87.

Nobel Prize controversy

His competition in the discovery of what the structure of DNA was like with Rosalind Franklin meant that, when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1962, he had to hear over and over again that the third man awarded that prize that year should have been a woman: Rosalind Franklin Although Rosalind died of cancer in 1958, four years before the award was given to her colleagues, it must also be said that she was never nominated.

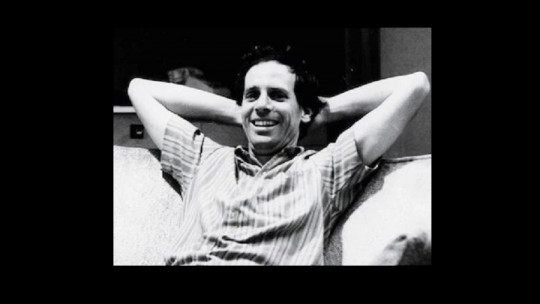

Maurice Wilkins published his autobiography in 2003, titled “The Third Man of the Double Helix,” a title that was chosen by the publisher, not him. In the introduction to his book, Wilkins wanted to make it clear that his main motivation for writing it was, precisely, to respond to accusations that he, Watson and Crick had illicitly appropriated Franklin’s findings. Such accusations had demonized the trio, but especially him, who defined himself as “the most prominent demon.”

Recognitions

As a reward for his long career in the study of DNA and being, practically, one of the co-founders of biophysics, Maurice Wilkins received numerous awards throughout his life:

- 1959: Elected Fellow of the Royal Society.

- 1964: Elected member of the European Organization for Molecular Biology.

- 1960: Receives the Albert Lasker Award.

- 1962: Receives the insignia of the Order of the British Empire.

- 1962: Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, together with Watson and Crick.

- 1969-1991: President of the British Society for the Social Responsibility of Science.