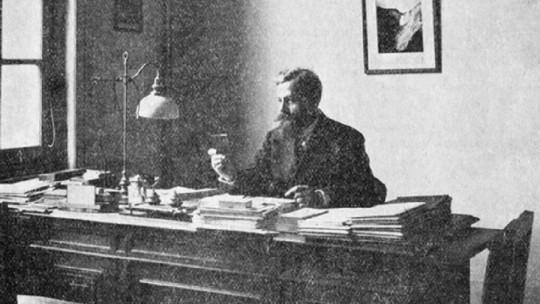

Gregorio Torres Quintero has been one of the greatest figures of Mexican pedagogy. His work in educational matters, especially with his innovative onomatopoeic method, earned him the recognition of the entire Mexican society at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th.

In addition to being a teacher, he was a politician, poet, orator, historian and a prolific writer of works, both pedagogy and history, which have served to not only better teach the history of his country, but also improve the way students learn. .

Next we will delve into the life of this educator, thinker and politician through a biography of Gregorio Torres Quintero “Master Goyito” for his students, who made the Mexico of his time a very updated country in matters of education and culture.

Brief biography of Gregorio Torres Quintero

Gregorio Torres Quintero, affectionately called by his students as “Maestro Goyito”, He is a very important figure in the history of Mexico, so much so that he is in the Rotoda of Illustrious Men of that country He was a teacher, pedagogue, politician, historian and writer and his desire to know how it was taught abroad made him one of the main motivators of several educational reforms, providing innovation to the Latin American country.

He was a firm defender that books were not a substitute for the figure of the teacher. The teacher, through his work, helps the students learn the content, which must be adapted according to their age since, according to Torres Quintero, one of the teaching errors of his time was thinking that Boys and girls learn like adults. Furthermore, he believed that if what was taught was limited to memorizing facts, dates and battles, the students would learn little.

Early years

Gregorio Torres Quintero He was born in Las Palmas, in the Mexican state of Colima on May 25, 1866 He was the son of a humble shoemaker named Ramón Torres, who is said to have arrived in Colima fleeing from a priest whom he had injured after impregnating his sisters. Gregorio’s father had to flee from Los Reyes, Michoacán, going aimlessly throughout Mexico until he reached Colima and had his son there.

Young Gregorio studied at the Colina Men’s High School and qualified as a tutor in 1883, beginning the teaching profession when he was only 17 years old. After teaching in the schools of his native state for four years, in 1888 he was awarded a scholarship to study at the National School of Teachers from which he would graduate in 1891. At this time he would meet Enrique C. Rébsamen, a Mexican educator of whom he would become a disciple

Return to Colima

In 1892 he returned to Colima and founded the Model School for primary, normal and graduate education. With the passage of time he would become the director of the Porfirio Díaz School and, later, he would become head of the Education and Charity Section of the Government Secretariat, and inspector of educational establishments throughout the state of Colima Carrying out this position he applied a series of educational measures, the Colimense School Reform, which made him well known in his country.

The 19th century had been a stage of profound and great educational transformations in the state of Colima, implementing changes in the teaching perspective. We moved from traditional Lancastrian doctrines to a school reform where the teacher was considered a key figure in learning. The Torres Quintero reform was motivated by the need to improve the educational panorama of the region.

On May 7, 1894, Gregorio Torres Quintero got the executive branch to promulgate a law prepared by himself in which It was determined that public education from that moment on was secular, free and obligatory In addition to making school education an obligation, the law addressed different issues such as teaching programs, types of exams, vacations, rewards and punishments and, ultimately, how courses and schools should be organized.

After the death of Rébsamen

During the period from 1898 to 1904 Gregorio Torres Quintero worked in the Directorate of Primary Instruction of the Federal District and Territories. He changed his position when Enrique Rébsamen died in 1904, becoming Head of the Primary and Normal Instruction Section of the Public Instruction and Fine Arts Section. Torres Quintero and Rébsamen did not differ in terms of educational creed, however, Gregorio was more in favor of objective or intuitive teaching to make it more enjoyable and attractive to students.

He would also be Professor of the Preparatory and Normal Schools of Teachers and Advisor to the Ministry of Education during this time. From 1910 He managed to serve as Vice President of the National Commission of Public Education and, a year later, he would become its president In August 1913 he returned to teaching, this time working at the National Preparatory School and also at the National Teachers’ School.

In 1916 he was sent by the constitutional government to the state of Yucatán with Governor Salvador Alvarado to be in charge of the Head of the Department of Public Education of the region. A little later he would take the opportunity to visit the United States and study everything related to school organization and modern pedagogical methods that were the latest trend north of the border. In 1918 he returned to Mexico City, dedicating himself again to writing school textbooks.

Last years and death

His trip to the United States would not be the only one he would make throughout his life. Motivated to learn first-hand what the latest trends in education were like around the world, he decided to travel to Europe, Asia, the Middle East and Africa during the period of 1926 and 1928, already a little older.

Just about six years after his last trip outside of Mexico, Gregorio Torres Quintero died in Mexico City on January 28, 1934, at the age of 70 Two years later, on May 15, 1936, he was declared Benemérito of the State of Colima and, almost 50 years later, in 1981, his remains were transferred to the Rotunda of Illustrious Men by decree of President José López Portillo y Pacheco , sanctuary where the most important figures in the history of Mexico are buried.

Contributions to Mexican education

Among the merits of Gregorio Torres Quintero are being the creator of the Public Instruction Law of his country He was a tireless critic of the textbooks of the time and the use that was being made of them, since many saw them as the perfect substitute for the figure of the teacher; However, Torres Quintero considered that the teacher’s image was essential to ensure that students acquired knowledge.

He was against teaching philosophical history in primary school and reducing teaching by trying to make students memorize facts, dates and battles without understanding anything. To combat this, Torres Quintero proposed a story in the form of a story in which the way of narrating it greatly stimulated the interest of boys and girls, who cannot be considered adults nor expected to learn how adults do. The information taught to them must be adapted. One of his best-known maxims on this issue is:

Another of his contributions, very popular in fact in his native country, is having created an onomatopoeic method for teaching reading and writing, which is still valid today in Mexico. This is based on natural sounds to be able to know letters, syllables and words, in addition to promoting phonetic awareness. This method, which was greatly inspired by Rébsamen’s ideas, played a very important role in the literacy of Mexicans at the beginning of the 20th century.

His new conceptions of education brought about an authentic golden age for education in Mexico, since He renewed the pedagogy of his native country by bringing new foreign ideas He collaborated with Justo Sierra and José Vasconcelos, and took much inspiration from Maria Montessori’s pedagogical method. He made Mexico acquire the most modern methods of the moment, address current pedagogical issues and try to make the most of the technology available in education.

Gregorio Torres Quintero: prolific writer

During his lifetime, Gregorio Torres Quintero wrote more than 30 books and articles on pedagogical, historical, traditional and short-story topics since, in addition to being a politician and pedagogue, He was also a historian, poet and orator In addition, he collaborated with several specialized magazines in the field of education, among them “La Educación Moderna”, “La Educación Contemporánea”, “Yucatán Escolar” and “La Enseñanza Primaria y Educación”.

Among his texts and stories we have:

About the language of Mexico

An aspect that we could consider controversial about Gregorio Torres Quintero has to do with his Law of Rudimentary Instruction, commissioned by order of the last secretary of public education of the Porfirio Díaz government, Jorge Vera Estañol. This law prioritized the literacy and Spanishization of all Mexicans to make the Spanish language the national language of Mexico

Gregorio Torres Quintero was aware of the linguistic diversity of the country, with the United Mexican States being a land full of indigenous languages that were still spoken at the beginning of the 19th century. He considered that they were an obstacle to the formation of the national soul, and he also thought that preserving them would imply economic difficulties, making it more worthwhile in his opinion to have all Mexicans speak Spanish. He was of the opinion that indigenous languages would only be relevant to antiquarians and linguists.

This opinion, in which he is in favor of the linguistic homogenization of Mexico, led him to create a rivalry with the Oaxacan professor Abraham Castellanos, a defender of Mexican multilingualism and its characteristic cultural heterogeneity. Castellanos considered that public schools should be provided with their own tools to learn agricultural work and other crafts, since it would be the best way to prepare students for adult life because the Mexican economy depended greatly on the land. that then.