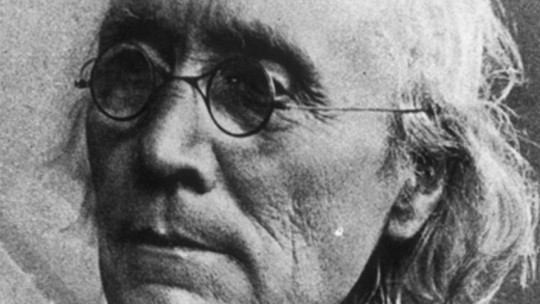

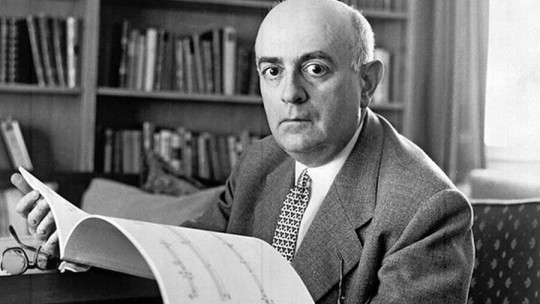

Theodor W. Adorno has been one of the great German philosophers, trainer of great thinkers such as Jürgen Habermas and a leading figure in the German Institute for Social Research.

In addition to studying philosophy and sociology, he always had a great interest in musicology, earning considerable fame by uniting these three disciplines in some of his works.

Adorno’s life was not easy since, being of Jewish descent, he had to deal with anti-Semitic threats and Nazi persecution. Below we will see more about his story through a biography of Theodor W. Adorno to better understand his career.

Brief biography of Theodor W. Adorno

Theodor Wiesengrund Ornament born on September 11, 1903 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany within a wealthy bourgeois family.

His father, Oscar Alexander Wiesengrund was a German-Jewish wine merchant and his mother, Maria Calvelli-Adorno, was a Corsican-Genoese lyric soprano. From a young age he became interested in music since his sister Agatha, a talented pianist, and his mother were responsible for giving him extensive musical training in his childhood.

Academic training

He attended the Kaiser Wilhelm Gymnasium, where he stood out as an excellent student In his youth he met Siegfried Kracauer, with whom he established a close friendship, despite being fourteen years apart. Together they read “Critique of Pure Reason” by Immanuel Kant, an experience that greatly influenced the young Adorno in his intellectual formation.

During the 1920s Adorno composed his first musical works It was avant-garde and atonal chamber music. After graduating with merit from the Gymnasium, Theodor Adorno enrolled at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt, an institution where he would study philosophy, sociology, psychology and music. In 1924 he obtained his degree by presenting a dissertation on Edmund Husserl: “Die Transzendenz des Dinglichen und Noematischen in Husserls Phänomenologie.”

At that time The young Adorno considered the possibility of devoting himself to music as a composer and writing several essays on musical criticism It is for this reason that in 1925 he went to Vienna where he studied composition with Alban Berg and would spend time with other key composers of the Second Vienna School, such as Anton Webern and Arnold Schönberg.

In essays on music, Adorno linked musical form with complex concepts drawn from philosophy. His musical works were not easy to read, with a very high intellectual involvement. The conceptual implications of the new music were not shared by the traditional Viennese School which is why Adorno decided to return to Frankfurt and abandon his musical career.

However, before leaving Austria Theodor Adorno had the opportunity to become intimate with other intellectuals outside of musical circles. He attended talks by Karl Kraus, famous Viennese satirist, as well as meeting Georg Lukács whose theory of the novel had impacted Adorno while at university.

Upon his return to Frankfurt he worked on his doctoral thesis under the supervision of Hans Cornelius Later, in 1931, he obtained his “venia legendi”, a diploma that accredited him as a teacher with his work. Kierkegaard: Konstruktion des Ästhetischen (Kierkegaard: construction of the aesthetic)

Exile

In 1932 he joined the German Institute for Social Research, an institution of Marxist inspiration attached to the University of Frankfurt. Given its ideas and the fact that there were Jews among its ranks, the rise of the Nazi party and the creation of the National Socialist regime meant that the institution was eventually dismantled. The government withdrew Adorno’s venia legendi and, seeing his life in danger, he ended up leaving the country.

First he traveled to Paris, but since France was approaching a fate similar to what Germany had experienced, Adorno would end up traveling to Oxford, England. He would remain in the English city until 1938, moving to New York, the city where the German Institute for Social Research had set up its headquarters in exile.

In 1941 he moved to California to continue collaborating with another member of the Institute, Max Horkheimer, writing “Dialectic of Enlightenment. Philosophical fragments.

Return to Germany

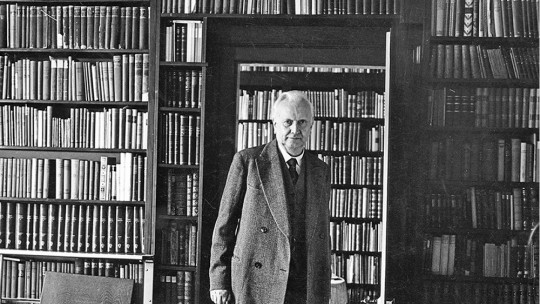

After the fall of the Third Reich and the end of the Second World War, Theodor W. Adorno returned to his native country in 1949 together with Horkheimer. In that same year assumed the position of director of the Institute for Social Research, reestablished in Frankfurt

It is this moment in which the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory was founded, a philosophical current that would have great importance in 20th century minds as important as Jürgen Habermas, who would also be a disciple of Adorno.

Last years

During the sixties he dedicated himself to directing the Institute, in addition to teaching at the University of Frankfurt. He took the opportunity to establish an intense relationship with the avant-garde artists of the moment like the writer Samuel Beckett, the composer John Cage and the filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni.

During this time Adorno was equal parts critical and inspiring towards youth protest movements. On many occasions they found inspiration and motivation in his particular vision of Marxism and rejection of reason as the ultimate goal. However, After the events of May 1968 in France, Theodor W. Adorno criticized “actionism,” that is, the privileging of protest action over critical argumentation This made him the subject of student protests, including the takeover of his own classroom.

Perhaps a little fed up with so much tension, Adorno decided to take a well-deserved vacation in the summer of 1969 doing mountaineering in Switzerland, where he suffered attacks of arrhythmia and palpitations. Although his doctors advised him not to go hiking or make great efforts, Adorno simply did not listen to them and decided to go on a mountain foray, from which he would never recover. He would die a few days later, on August 6, 1969 in Visp, Switzerland due to an acute myocardial infarction. He was 66 years old.

When he died, Adorno was working on his aesthetic theory, a work of which he had already made two versions and was going to carry out the last revision of the text. This posthumous work would be published in 1970.

Works of this philosopher

Adorno never lost interest in musicology In fact, he was a prolific author of works related to this discipline.

The fact of having established a relationship with the Viennese musical avant-garde and having rubbed shoulders with figures such as Arnold Schönberg, Eduard Steuermann and Alban Berg led him to publish several important works in the field, such as Philosophy of new music (1949), Versuch über Wagner (1952), Dissonances. Music from a managed world (1956), Mahler (1960) and Der getreue Korrepetitor (1963).

But he not only published his own works in musicology, but also helped other figures in the field to compose their works. One case is that of Thomas Mann, who used Adorno’s advice for the musicological part of his novel. Doctor Fausto (1947), which is in tune with the theses of the philosophy of new music.

In the field of sociology, the two main themes of Adorno’s critical reflection are, on the one hand, the predominant tendencies in modern reality and, on the other, the utopian tension towards the dimension of another present, reified and alienated. His dialectical-Hegelian and Marxist training makes Adorno consider denial as an important tool of criticism of the society. In “Dialectic of Enlightenment” Adorno offers an analysis of modern mass society, drawn directly from his visions of postwar American culture.

Design a vision for how it behaves contemporary man, debased by the cultural industry of his time and firm believer in the myth of scientific rationality, from its origins in the 18th century Enlightenment to the present. He will also develop this theme in other works such as Minimal morality (1951), The authoritarian personality (1950), Negative dialectic (1966) and Stichworte. Kritische Modelle (1969).

Philosophically, he reread Hegel’s work in his Three studies on Hegel (1963). He abandons the abstract intellectualism of the Enlightenment without rejecting the idealization of dialectical reason. Adorno’s intervention in this work is characterized by his repudiation of phenomenology Adorno criticizes culture in his interventions especially focused on literature as art, collected mainly in Prisms. Cultural and social criticism (1955) and in Literature notespublished in four volumes between 1958 and 1974.

Shortly before his death, Adorno finished his aesthetic theory, although he had a review to do. In it he reaffirmed the urgency, for art itself, of the link between criticism and utopia Art can only be justified as a memory of the suffering that has been accumulating throughout history, which requires rescuing that “offended” life, making art a kind of act of reparation for personal grievances.

It should be said that many works of Theodor W. Adorno are difficult to include clearly within the field of philosophy or sociology, since the boundaries between both disciplines are very blurred in his thought. He even touches on aspects of psychology, as is the case of his collaboration with Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford who carried out fundamental research on the psychology of antisemitism, The authoritarian personality (1950). Ornament He contributed to this work by developing scales for measuring fascist tendencies

He criticized positivist sociology in Sociological (1956) in collaboration with Max Horkheimer. For Adorno, positivism had lost sight of social reality, losing focus on the primary needs of existence. In Soziologische Schriften (1972), Adorno highlights the need to apply the dialectical method to the knowledge of contemporary society.