The musculoskeletal system refers to the set of tissues and organs that allow living beings to move and respond to environmental stimuli. In the case of humans, this intricate work of biomechanics has 206 bones, more than 650 muscles and 360 joints, of which 86 are located in the skull.

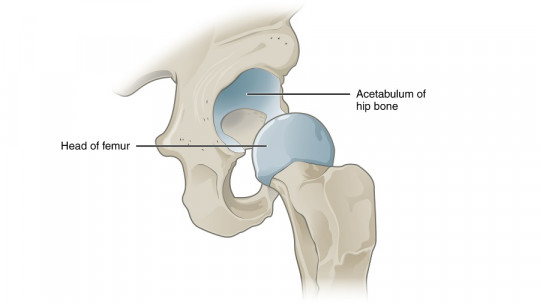

When we talk about the formation of movement in vertebrates, we automatically think of muscles and bones, since they are “the bulk” that causes force when responding to a stimulus. In any case, we must not forget about the joints, since they are the ones that join two or more bones so that they maintain their structure or, failing that, enabling movement.

Based on this premise, we find it interesting to investigate the world of joints and everything that their anatomy and variability entails. In the following lines, we tell you everything about cartilaginous joints and their particularities

What is a cartilaginous joint?

As indicated in the medical dictionary of the Universidad Clínica Navarra (CUN), A joint is a specialized structure in the area of union between two or more bones or, failing that, between bone and cartilaginous structures Normally, when we think of joints, the knee and elbow come to mind, but these obvious formations are in the minority.

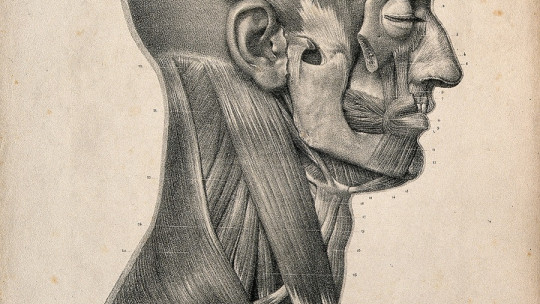

Without going any further, 86 joints are found in the head, of which the atlanto-occipital head and the temporomandibular joint are the only mobile ones. In the skull, some of the joints are nothing more than the “glue” between the flat bones that protect our brain, but how they fit the classic definition (union of two or more bones), they fall within this great anatomical category. .

Within the grouping of joints, we find three large categories These are the following:

Cartilaginous joints are in the middle at a physiological level, as they are more mobile than fibrous joints but less than synovial joints, which represent the maximum range of mobility. Furthermore, it should be noted that cartilaginous joints also form the growth regions of the long bones and intervertebral discs of the human spine.

Types of cartilaginous joints

The cartilaginous joints include the symphysis and synchondroses. We tell you its particularities in the following lines.

1. Synchondrosis

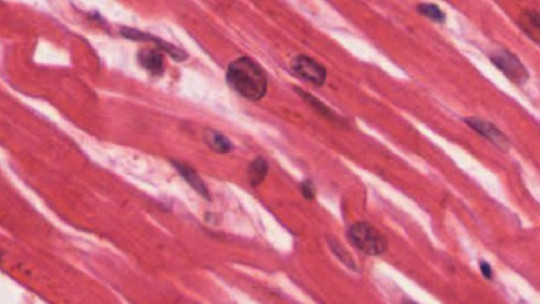

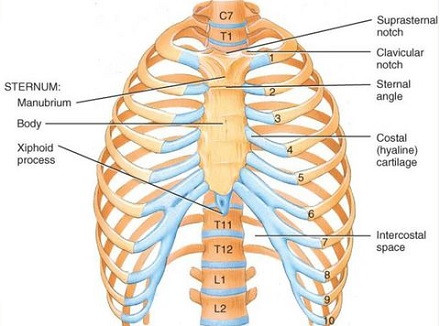

In synchondrosis, the connecting element between the bones involved is hyaline cartilage, compared to the fibrocartilage of the symphysis (although some symphysis also have hyaline cartilage). Furthermore, on this occasion the training is temporary.

An example of this is the joint present between the basilar process of the occipital and the body of the sphenoid, when both structures are still cartilaginous because they have not completed their development. Once the relevant tissue maturation occurs, both articular surfaces fuse and the synchondrosis disappears. They usually appear between bony growth structures allowing a certain degree of movement, but they completely ossify over time.

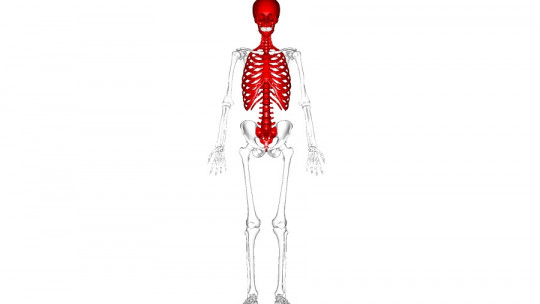

On the other hand, it is also worth noting that There are a couple of permanent synchondroses One of them is the first sternocostal joint, where the first rib and the manubrium of the sternum join. This one stands out above the rest, since the other rib-sternum junctions are of the flat synovial type. The other permanent synchondrosis is the petro-occipital synchondrosis, between the occipital and stony bones of the skull.

Synchondroses between long bones of growth

In the long bones of human beings (such as the femur) two very specific structures are distinguished: the epiphysis and the diaphysis The epiphysis is each of the two ends of the long bone, the area where the joints are located, wider than the diaphysis. For its part, the diaphysis is the area between both epiphyses, which is covered with a hard periosteum and in its internal area contains the bone marrow, where circulating cellular elements (red blood cells and others) are synthesized.

Synchondroses are usually located in the growing long bones between both epiphyses and the central diaphysis. These relatively “soft” joints allow the body of the bone to elongate and separate the bone conglomerate into three distinguishable sections, as if they were three bones (epiphysis-cartilage-diaphysis-cartilage-epiphysis). Ultimately, these cartilages ossify and form an anatomical whole.

2. Symphysis

In this type of cartilaginous joint, The bones in contact are first joined by a sheet of fibrocartilaginous nature (fibrocartilage), which fuses the components into an anatomical structure Unlike the synchondroses that we will see later, symphysises are permanent throughout the life of the individual.

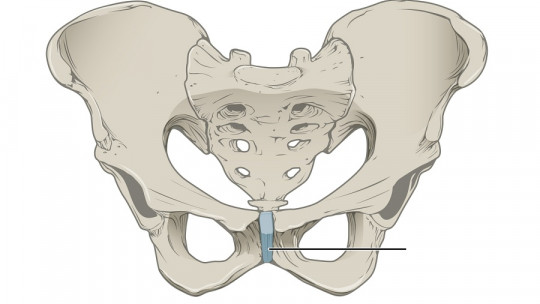

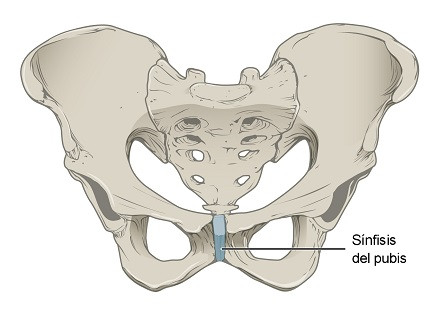

A clear example of a symphysis is the pubic symphysis, although there is also one present in the jaw, in the sacrococcygeal region, in the sternum and, without going any further, between the vertebrae of the spine. Simply put, at the symphysis two separate bones are connected to each other by cartilage.

The pubic symphysis

The pubic symphysis (the most striking of all) is defined as a cartilaginous joint located at the confluence of the two pubic bones, formed by a small fibrocartilaginous disc that is placed between two narrow sheets of hyaline cartilage In addition, this disc is reinforced by a pair of especially interesting ligaments: the lower and upper pubic ligaments. These provide enormous stability to the osteoarticular conglomerate of the pubis.

Curiously, the female pubic symphysis is covered by adipose tissue, which makes up the well-known “mons of Venus.” The characteristic female pubic hair grows on this structure, but it also has glands that secrete hormones involved in sexual attraction. Even the most seemingly anecdotal anatomical variation has clear evolutionary significance.

Cartilage joints and the spine

As we have said, intervertebral discs are fibrocartilaginous symphysis, which are located between each of the 26 vertebral bones that provide axial support to the trunk and provide protection to the spinal cord, which allows the transmission of information to our nerve endings.

You’ve probably wondered why the elderly seem to shrink as they get older, right? Interestingly, much of this shrinkage is due to the degradation of the intervertebral joints, in addition to osteoporosis and other bone damage and remodeling processes. The force of gravity acts on the spine and, over the years, the vertebrae compress these discs and squeeze together.

After the age of 40, people usually lose one centimeter of height every 10 years, partly due to this compression resulting from the wear and tear that occurs in the intervertebral discs: We remember again that these are cartilaginous joints of the symphysis type. As they age, an average human being can lose 2 to 7.5 centimeters of height throughout their life, a value that may seem tiny but is more than notable.

Osteoporosis is also essential to understand this reduction in height, since in it, bones are reabsorbed and destroyed at a higher rate than their synthesis As a result, some long and short bones become even thinner and shorter over time, becoming much more fragile and prone to fractures. It is no coincidence that almost no one presents a vertebral fracture before the age of 50.

Summary

As you may have seen, cartilaginous joints go far beyond the merely anecdotal, because thanks to them, for example, the spine is supported and a large part of the reduction in height in adult human beings can be explained. On the other hand, thanks to the cartilaginous joint of the pubis, the mons pubis can manifest in women, which seems to play a non-negligible role in sexual attraction.

With these lines, it is more than clear to us that, in the human body, almost everything has a reason. Except for a few vestigial structures (such as wisdom teeth), every tissue, cell and point of attachment has a specific function, more or less important to maintain internal homeostasis or carry out movements in the environment.