The daily experience of human beings, and their interaction with the ins and outs of reality, leads them to think that everything that surrounds them has two possible substances: the tangible and the intangible. Or what is the same: what you can perceive and what you cannot through the organs of sensation.

However, the truth is that the “impression” of our senses exclusively announces a perspective of things, sometimes misleading or biased, such as the straight line of the horizon (compared to the sphericity of the Earth) or the apparent movements of the sun. (which seems to rotate around the planet and not the opposite).

This veil, inherent to the limitations of our biology, fueled a certain skepticism among some of the greatest thinkers of recent history; which assumed the witness of those who preceded them in the search for an elemental substrate for all things in the world, beyond the perceptive dictatorship of a simple observer.

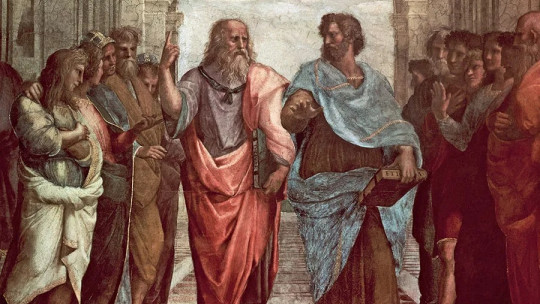

Given this situation, it is located physicalism, a philosophical model which aims to answer one of the great dilemmas of history: what makes up reality. As the years went by, it emerged as a materialist alternative in the particular field of Ontology, in obvious opposition to Platonic idealism and Cartesian dualism. Let’s see it in detail.

What is physicalism?

Physicalism is a branch of philosophical knowledge, whose aim is to explore reality. In his theoretical corpus assumes that the nature of what exists is limited exclusively to the physical, that is, to matter (or energy understood as the constituent fabric of any tangible entity). It is therefore a form of monism, which reduces the complexity of the universe we inhabit to its most basic substance, and which embraces materialism as inspiration for the elaboration of its basic concepts (as well as naturalism).

This perspective is based on the epistemological branch of the philosophy of mind, which is why it assumes that the ethereal substance that we refer to as “soul” and/or “consciousness” must also be supported by tangible reality. In this way, the brain would serve as an organic support for all psychic phenomena, implicitly rejecting the existence of the spirit and/or God. From such a perspective the basic foundations of almost all religions would be denied this precept being the main cause of controversy that it had to face since its birth.

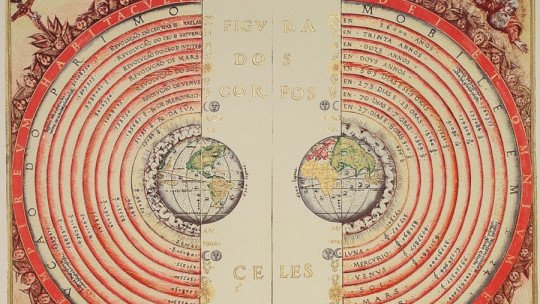

The fact of considering any activity of the mind as an epiphenomenon of organic reality, reducible to the action of hormones and neurotransmitters on brain physiology, represented a confrontation with Descartes’ dualistic thesis (Cartesian dualism). According to such a philosophical perspective, with a wide tradition in the old continent, the physical (extensive) and the mental (cogitans) would be the two basic dimensions of reality (both equally important) and would connect in an absolute way with each other (both physical as well as mental could be the cause or consequence of an object or a situation).

The physicalist theses would demolish the ideas of dualism from the base, since the mental would necessarily be a cause of the physical, without in any case any relationship in the opposite direction could occur. Following this idea, the links that give shape to any chain of events would have a tangible substrate, being susceptible to analysis and understanding with the tools of the natural sciences (which is why his proposal has been valued as a naturalistic philosophy). In this way, all mental processes would have their reason for being in the brain, and through its study its gears and operating mechanisms would be discovered. It would therefore be assumed that mental things do not have their own reality, but always depend on the physical.

Physicalism has been criticized by countless scholars, based on its comparison with materialism. However, it differs from it by the inclusion of “energy” as a form of matter in a state other than the tangible (which materialism never contemplated), which allows it to adapt to spaces in which it never participated. (like the analogy between mind and brain).

Thus, in its applied form it emerges as a working scientific hypothesis that reduces everything to the material, and that does not consider the plausibility of the theory from which it is based. Therefore, opt for an application of an operational nature, including the possibility that the phenomena of Psychology can be reduced to the neurological/biological

In the following lines some of the fundamental ideas relating to the theoretical basis of stratification will be presented, which has been used to explain physicalist reductionism, and without which it is difficult to understand its dynamics in action.

Physicalist reductionism: stratification

Cartesian dualism postulated an ontological division for the essence of all things in reality, with two different but widely interconnected dimensions: matter and thought or cognition However, physicalism proposed a much more complex structure for this natural ordering: stratification. Its logic involves the succession of many levels, following a hierarchy of relative complexities that would start from the essential to progressively ascend to much more elaborate constructions.

The body of any human being would be in its essence an accumulation of particles, but it would become more sophisticated as it reaches the higher levels of the scale (such as cells, tissues, organs, systems, etc.) to culminate in the formation of a consciousness. The highest levels would contain in their own composition the lower ones in their entirety, while those located at the bases would be devoid of the essence of those that occupy the top (or would only be partial representations).

Consciousness would be a phenomenon dependent on the activity of an organ (the brain), which would be less complex than it. Therefore, the effort to understand it (anatomy, function, etc.) would imply a way of enclosing knowledge about how one thinks, and ultimately an approach to one’s own consciousness. It is inferred from this that There is no thought as a reality independent of the physical base that would make it possible. This process involves an inference of higher strata of this hierarchy from the observation of the lower ones, generating analogies from one to another and thus understanding that their essence is largely equivalent. From such a prism, phenomenology (subjective and unique construction of meaning) would depend only on physical qualities inherent to biology.

It is at this point that many authors point out implicit reductionism to physicalism Such criticisms focus (above all) on the potential existence of differential characteristics for each of the levels, which would make an adequate comparison between them difficult (of the part with the whole) and would leave the question of the relationship between mind-body unresolved. . The currents that most vehemently questioned this physicalism were anti-reductionism (due to the excessive parsimony of its approaches and the naivety of its logical deductions) and eliminativism (which rejected the existence of levels or hierarchies that could be established between them). .

Main opponents of physicalism

His main critics were Thomas Nagel (who pointed out that human subjectivity cannot be captured from the perspective of physicalism, as it is closely associated with individual perspective and processes) and Daniel C. Dennett (although he supported physicalism, he fought to maintain the idea of free will, since he understood it as an inalienable quality of the human being). The denial of this precept, which is given cardinal value in the context of religion, also exacerbated the complaints of Christian thinkers of the time.

Although they were all very notable oppositions to physicalism, the most relevant of them arose from subjective idealism (George Berkeley). Such a doctrine of thought (also monistic) did not conceive of the existence of any matter, and was oriented only towards the mental plane of reality. It would be a way of reflecting that would be located within immaterialism, to the point of conceiving a world formed only by consciousness. As in the case of physicalism, idealism would explicitly reject Cartesian dualism (since such is the nature of monisms), although doing so in a way opposite to that.

The idealist vision would locate the axis of reality in the individual who thinks, and who is therefore an agent subject in the construction of everything he or she comes to know. Within this perspective, two variants can be differentiated: the radical one (according to which everything that exists before the eyes of an observer is created by him/herself in a process of conscious ontology, so nothing would exist outside the activity of the own mind) and the moderate one (reality would be nuanced by one’s own mental activity, in such a way that the individual would adopt a particular perspective on things depending on the way he thinks and feels).

The debate between the two perspectives is still active today, and although there are certain points of convergence (such as full conviction about the existence of ideas, despite divergences in nuances) their visions tend to be irreconcilable. They suppose, therefore, antagonistic ways of perceiving the world, which have their roots in what is perhaps the most basic question that philosophy has in its repertoire: what is the human being and what is the fabric of reality like? in which he lives?