Materialist Eliminativism is the philosophical position that denies the existence of “mental states,” proposing to eliminate the explanatory apparatus that has led us to understand the “mind” as we have done since the 17th century, and create another that takes up material conditions. of existence.

Although it is a radical proposal, Materialist Eliminativism has had an important impact on the way of doing philosophy and a special impact on contemporary psychology. What is eliminativism and where exactly does it come from?

Eliminativism: do mental states really exist?

The “mind” is a concept that we use so frequently that we could hardly doubt its existence. In fact, to a large extent scientific psychology has been dedicated to studying processes such as common sense, beliefs or sensations; derived from a specific and fairly widespread understanding of the “mind” or “mental states.”

Already in the 17th century, Descartes had insisted that the only thing that human beings cannot doubt is our ability to think, which laid the foundations for the development of our current concept of the “mind”, “consciousness”. ” “mental states” and even modern psychology.

What Materialist Eliminativism does is take up all this, but to open a debate about whether these concepts refer to things that really exist and therefore, it is questioned whether it is prudent to continue using them.

It is then a contemporary proposal that says that our way of understanding mental states has a series of shortcomings fundamental, which even make some concepts invalid, such as beliefs, sensations, common sense, and others whose existence is difficult for us to question.

Some fundamental philosophical proposals

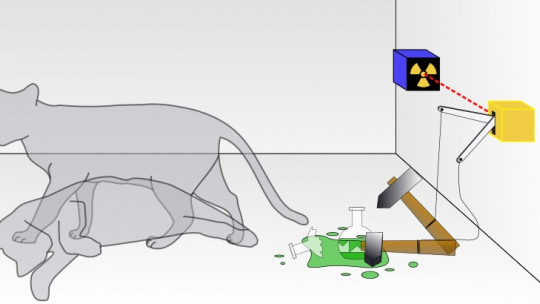

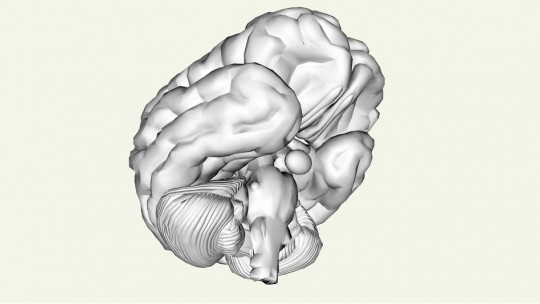

Materialist Eliminativism proposes that, beyond modifying the way in which we have understood the mind, what we should do is eliminate the entire explanatory apparatus that has led us to describe it (that is why it is called “eliminativism”). The reason: mental states are non-existent things, In any case, they would be cerebral or neuronal phenomena with which a new explanatory apparatus based on material reality would have to be formulated (that is why it is “materialist”).

In other words, Materialistic Eliminativism analyzes some concepts about the mind and mental states, and concludes that they are empty notions because they often reduce to intentional properties or subjective experiences that do not refer to something that has a physical reality.

From there a second proposal is derived: the conceptual framework of neuroscience should be the one that explains mental states, because these sciences can refer to material realities.

As in all philosophical currents, there are different nuances depending on the author; There are those who say that the issue is not so much that mental states do not exist, but that they are not well described, so they should be replaced by concepts that have been suggested in brain studies. In this same sense, the concept “qualia” is another proposal that has highlighted the gap between explanations of subjective experiences and physical systems especially the brain system.

Finally, Materialist Eliminativism has also raised questions, for example, the question about where the limits are between eliminativism and materialist reductionism.

Eliminativism has not only been materialist

Eliminativism has had many facets. Broadly speaking, we could see some shades of eliminativism in several of the philosophical and determinist proposals of the 18th century that questioned concepts also related to psychology, such as “freedom” or the “self.” In fact, materialism itself is already an eliminativist position, as the conditions of existence of non-material elements are rejected.

We usually know as Materialistic Eliminativism the position that specifically denies the existence of mental states. It is a more or less recent proposal, which arises from the philosophy of mind and whose main antecedent is the work of the philosopher Charlie Dunbar Broad; but it formally emerged in the second half of the 20th century among the works of Wilfred Sellars, WVO Quine, Paul Feyerabend, Richard Rorty, Paul and Patricia Churchland, and S. Stitch. That is why it is also known as contemporary Materialistic Eliminativism.

Formally, the term “Materialistic Eliminativism” is attributed to a 1968 publication by James Cornman titled “On the elimination of “Sensations” and Sensations.”

Impact on modern psychology

In its more modern versions, Materialistic Eliminativism proposes that our understanding of “common sense,” “mental states,” or psychological processes such as desires or beliefs is deeply mistaken because they arise from postulates that are not truly observable, thus which its explanatory value is questionable.

In other words, Materialistic Eliminativism allows update discussions on the mind-body relationship (using the mind-brain formula) and suggest, for example, that beliefs, since they do not have a physiological correlate, should be eliminated or replaced by some concept that does have a physical correlate; and in the same sense is the proposal that, strictly speaking, sensations are not really “sensations” but are brain processes, so we should reconsider their use.

In short, from Materialist Eliminativism common sense psychology and cognitive sciences are questioned It is not surprising that in recent decades this position has gained a lot of strength, especially in debates on cognitive sciences, neurosciences and the philosophy of mind. Furthermore, this has been a topic of discussion not only for studies of the mind but also for those who analyze the processes of construction and transformation of modern theoretical frameworks.

Without a doubt, it is a current that has not only put fundamental questions on the table about our way of understanding ourselves and what surrounds us, but from there, it points out that the most popular explanations are largely insufficient as well as capable of being constantly updated.