The 19th century is a turbulent century. Social and material changes are accelerating and, with them, intellectual and artistic expressions. Aestheticism is one of them, a broad current that includes many others in the literary and artistic field

In this article we are going to take a brief tour of the ideals advocated by aestheticism and its most representative authors.

What is aestheticism?

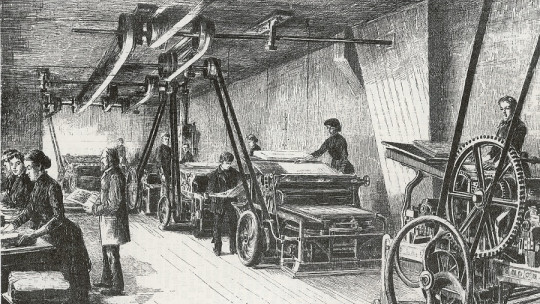

During the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution that began at the end of the previous century reached its peak.

The West was very proud of its mechanical capacity, and science and positivism were crowned as the greatest exponents of a civilized and modern world. In literature, realism first and naturalism later picked up the baton of these ideas and they limited literary creation to a mere analysis of the surrounding reality.

The second current, naturalism, led by authors such as Émile Zola, went further in its analytical study of reality and the human being, using the pen as a tool for the dissection of the human psyche. All very orderly, pragmatic and scientific, in correspondence with the thinking of the time

Of course, we do not mean by this that naturalistic works are “bad.” Not at all. Most of them are indisputable monuments of universal literature. What we want to point out is the progressive “scientification” of a world that was already only interested in progress as the only sign of civilization and modernity.

This is how a group (very heterogeneous, yes) of artists saw it, who were witnesses of how spiritual and aesthetic values were lost in favor of industry, mechanics and production The world of the factory devoured the world of artistic creation.

Little by little, a series of literary and artistic currents that react violently against this industrialized world begin to appear in Europe (especially in the most industrialized countries, such as France and the United Kingdom).

All these manifestations are usually included with the label of “aestheticism”, since His main motivation was a return to art as an exaltation of beauty ; an uncontaminated, pure, primitive, spiritual art. Thus, the main idea of aestheticism was “art for art’s sake”, the cult of beauty itself, beyond morality, religion and politics. In reality, what this current represented was a profound evasion of a gray and automated world that did not satisfy the soul of the artist. Against the smoke of the factory, worker exploitation and massification, the followers of aestheticism advocated escape to other worlds, to other realities.

The roots of aestheticism are found in a year as premature as 1835, when Romanticism was still all the rage in Europe. Specifically, in the prologue of the novel Mademoiselle de Maupinby Théophile Gautier (1811-1872), we can read the following:

“Things are beautiful in inverse proportion to their usefulness. There is nothing truly beautiful that serves any purpose. “Everything that is useful is ugly.”

These phrases, simple and forceful, are the authentic manifesto of the aestheticist movement, since they include its main ideas: on the one hand, the consecration of art for art’s sake (that is, beauty without concealments or excuses) and, on the other , the reaction against industrialization and mass production which are seen as something vulgar and lacking beauty.

Movements adhered to aestheticism

As we have commented, aestheticism was not a homogeneous current. Throughout the 19th century we find several movements that adhere to this thought, but present their own characteristics. Let’s look at them below.

1. Parnassianism

It was the first of the aesthetic movements, since it emerged in the 1850s It is a strictly literary movement; The name comes from Mount Parnassus, where the muses lived. The founders and leaders of the movement were the poet Leconte de Lisle (1818-1894) and the aforementioned Théophile Gautier who, with his poem Enamels and cameosprepared the ground for the Parnassianist aesthetic.

The very name of the poem is significant enough: an exaltation of beauty, of details, of decorative objects. The Parnassianist movement reacted equally against naturalism and against romanticism. Against the first, due to its excessive dose of reality and analysis. Against the second, due to its exacerbated exaltation of personal feelings, considered excessive by aestheticians.

2. Decadentism

Also of French origin, the nomenclature was given in a derogatory manner by nineteenth-century academic circles, surely due to the style that the authors used in their compositions, irrational, pessimistic and full of “strange” and incomprehensible similes Like its Parnassianist companions, decadentism seeks an evasion of the mechanical and vulgar world of the bourgeois class, and proposes the cult of absolute beauty, without any type of limit.

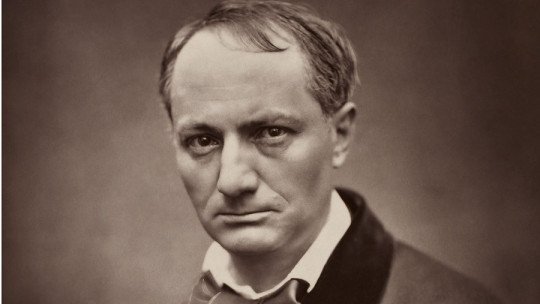

The greatest exponent of this current is, without a doubt, the poet Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), one of the members of the group known as “the cursed poets.” Baudelaire’s poetry served as an inspiration to many aesthetic artists, who were especially inspired by his work. The flowers of Evil (1857), a controversial work that earned him a trial for “offenses to public morality.” If the decadent artists wanted to offend the prevailing bourgeoisie, Baudelaire had succeeded.

Another notable work within the decadent movement, due to the great impact it had, was Unwillingly (1884), by JK Huysmans. Its protagonist, the eccentric Des Esseintes, became the symbol of dandyism, closely linked to aestheticism through figures such as Oscar Wilde

The latter is precisely another of the prominent names within aestheticism and decadentism in particular. Wilde advocated throughout his life absolute beauty, stripped of all morals and conventions.

His extreme aestheticism leads him to dress eccentrically, giving importance to details, colors and originality. This way of dressing, which many other dandies of the time followed, also meant a reaction against the bourgeoisie , since the ideal masculine attire that had been imposed since the beginning of the 19th century was far from any fantasy and perfectly represented the idea of “chain production” that characterized industrial society. Dandies like Oscar Wilde, on the other hand, wore silks, bright colors, large capes and hats; In short, anything that attacked this sober and corseted masculine ideal.

Wilde’s great decadent work is The Portrait of Dorian Gray (1890), clearly related to the already mentioned Unwillingly, by Huysmans. Wilde’s role within the aestheticist movement was so great that many specialists maintain that aestheticism ended with the author’s prosecution for homosexuality in 1895 and, of course, with his death in 1900.

3. Symbolism

And again we traveled to France to find the origin of this aesthetic trend. The main characteristic of symbolism is its aesthetic expression through symbols In the same way as their sister movements, they reject the exacerbated romanticism of authors such as Victor Hugo and the realism and naturalism of Zola and Flaubert.

Symbolism relies on the imagination to give free rein to its creations. Dream visions and subjectivity run rampant in symbolist works, both literary and pictorial. To achieve this, artists have no qualms about consuming substances such as opium or hashish, which make them escape towards those desired worlds.

This is why the majority of these authors are included, like Baudelaire himself, in the group of “cursed poets”: Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud (who, by the way, were lovers and carried out one of the most scandalous trials). of the time, since Verlaine shot Rimbaud on two occasions) are two greats of the Symbolist movement in literature, while Puvis de Chavannes, Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon are great in painting.

4. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

In 1848 the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was created in England , founded by artists Dante Gabriel Rosetti (1828-1882), William Hunt (1827-1910) and John Everett Millais (1829-1896). This brotherhood constituted a reaction against the violent industrialization that the United Kingdom was experiencing and against all its consequences: the massification of cities, the brutalization of human beings, productive anxieties and the rise of industrial “ugliness.”

To fight against all this, or rather to escape from this world that they did not like, the Pre-Raphaelites returned to painting before Raphael (that is, to medieval painting and the Italian Quattrocento), where they found true spirituality and authentic beauty. Pre-Raphaelite works are inspired by Gothic altarpieces; His figures are stylized and almost ethereal, and his creations contain a great abundance of details. It is, once again, the cult of absolute and sacred beauty, beyond morals, politics and religion

One of the most emblematic paintings of this group is The beloved, by Rossetti, painted in 1866 and inspired by the Song of Songs from the Bible. Despite his source, we should not believe that Rossetti’s intention is religious. We have already said that the Pre-Raphaelites, like good aestheticians, advocate art for art’s sake. No, Rossetti’s intention is to rescue the primitive beauty of the biblical poem (which is, ultimately, a powerful love song) and capture this beauty on the canvas.

Thus, we can see a beautiful young redhead (this hair color became fashionable through this group of painters), dressed in delicious and colorful clothing and exotic jewelry. Around her, an entourage painted with exquisite detail, showing faces as beautiful as that of the bride. The work is, without a doubt, a hymn to immortal beauty, which is beyond time and space.

5. The Art Nouveau

Without a doubt, the Art Nouveau (known as Modernism in Spain and Judgenstil in countries such as Switzerland and Germany) draws on the aesthetic currents of the late 19th century, and takes from them art for art’s sake, detail and careful, artisanal manufacturing. The movement of the Arts & Crafts , founded by the way by the Pre-Raphaelite William Morris and which advocated a return to artisanal forms of production. Once again, we are facing a reaction to industrialization and mass production.

He Art Nouveau escapes, like its predecessors, towards dream and fantasy worlds To do this, it borrows solutions from other periods, such as the Middle Ages or the Renaissance, and also from other cultures, such as the Japanese. An important part of his inspiration, especially in artists like Antoni Gaudí, comes from nature, that perfect, harmonious and beautiful world from which human beings have distanced themselves.

He Art Nouveau It probably represents one of the last cries of aestheticism. After the outbreak of the First World War and the emergence of the existential anguish that characterizes the intellectuals of the early 20th century, the avant-garde will take over in the protest against the bourgeois world. The same, but with different voices.