There are several people who have the nickname “the first archaeologist” or “the father of archaeology”. In addition to Ciriaco of Ancona, a character we are talking about today, we also have Johan Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768) who, in the 18th century, revolutionized the way of codifying the history of art.

The Enlightenment to which Winckelmann belonged was the beginning of scientific disciplines as we know them, but already in the Renaissance we find people interested in collecting reliable information from that classical past that they admired so much. Cyriaco of Ancona (1391-1455) is one of them.

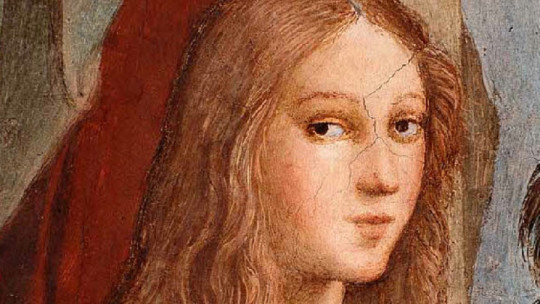

Today, we review the life of the one who was nicknamed Antique for his passion for works of art from classical antiquity, Ciriaco of Ancona.

Brief biography of Ciriaco of Ancona, the “first archaeologist”

Cyriacus of Ancona (or Kyriacus Anconitanus, as his name was known in Latin, the lingua franca of the time) was a child of his time. Born in the last years of the 14th century, he lived the humanist splendor of the Italian courts of the 15th century and was imbued with the passion for antiquity, which was all the rage among the intellectuals of the time. His status as a merchant opened the doors for him to travel throughout the Mediterranean, Egypt and even the Ottoman Empire, with whom his city, Ancona, maintained very good relations.

The Republic of Ancona in the great century of maritime trade

To talk about the Italian peninsula in the 15th century is to talk about trade. The trade routes, which penetrated from the east (especially through Venice, a true bridge between cultures) continued their way through the various Italian states and then turned towards the north; specifically, towards Flanders, from where they continued until they reached England. All of Europe was connected by a prosperous trade channel that enriched the various countries and the various families that were engaged in trade.

Precisely through Ancona a commercial corridor passed that fiercely disputed with Venice its predominance in the Mediterranean area. This route brought goods from the east that did not pass through the Serenissima, so Venice did not look favorably on the economic and political power that its rival was acquiring. Ancona, furthermore, It maintained excellent relations with the Byzantine Empire and with its enemy, the Ottoman Empire, so its situation could not be more prosperous.

Precisely in this rich and cosmopolitan city, bathed by the waters of the Adriatic, Ciriaco Pizzecolli, later nicknamed “Ciriaco of Ancona” due to his origin, was born in 1391 into a wealthy family dedicated to commerce. From a very young age, Ciriaco dedicated himself to the family business, but he soon realized that his true passion was the study of antiquity, so he abandoned his father’s company and began to train, generally, self-taught.

Self-taught and passionate

Ciriaco’s passion for the classical past knew no limits and his thirst for knowledge was great. His family background was of great help in his formation, since, in addition to wealth, the Pizzecolli family had contacts with all the fondachi of the Mediterranean, that is, with all the commercial embassies spread across places as diverse as Greece, Byzantium or the Ottoman Empire.

So that, His status as a merchant was the best passport to move around Europe and the Middle East. Pope Eugene IV himself and Cosimo de Medici encouraged his excursions and his investigations, riding the bandwagon of the “fever for the classic” that was beginning to emerge and would mark the aesthetics and culture of the 15th century.

And Ciriaco did not stop traveling: first, to various places on the Italian peninsula (1423-1424); then, Greece and Constantinople (1425-1432), and, later, Egypt (1435-1438). During his travels he drew everything he saw and transcribed ancient inscriptions; sometimes, it must be said, with some failures. Ciriaco was, in fact, the first European to bring to his continent information about the pyramids and hieroglyphics, unknown in Europe. But, despite his dedication, Egyptomania would not arrive until several centuries later, with Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign and the discovery of the Rosetta stone.

Very valuable testimony of the past

In addition to the invaluable information that Ciriaco extracted about the pyramids and the ancient Egyptian language (undeciphered, of course), The intrepid traveler made a sketch of the Parthenon in Athens that constitutes a unique testimony of how the monument was before it exploded (literally) under the Venetian gunpowder , in 1687. Ciriaco scrupulously reproduced its appearance, with the pertinent annotations, which constitutes a unique document. Furthermore, he was the first to call the Parthenon by its classical name (derived from Parthenos, “virgin”, “maiden”, appellation of the goddess Athena) instead of calling it “Church of Saint Mary”, which was the invocation it had received. after the Christianization and consecration of the building.

Ciriaco’s profuse documentation, the result of the numerous trips and studies he made, was compiled in his magnum opus, Comment (The Commentaries), which served as a working example for many later scholars. Unfortunately, The six volumes of the work were lost in the fire of 1514 that devastated the library of Alessandro and Constanza Sforza, in Pesaro, where they were kept.

The result is that, of the lifelong undertaking that our character carried out (no less than 30 years traveling and collecting information), only a few scattered files remain, mostly preserved in the Vatican Library. Famous for its peculiarity is his drawing of a giraffe, executed when this animal was barely known in Europe and, more than likely, no European had seen one. This demonstrates that Ciriaco Pizzecolli from Ancona was not only interested in antiquities, but also in all areas of knowledge (he was humanist for a reason, of course).

On the other hand, it was he who started (or, at least, greatly contributed to it) the collecting fever that possessed all the wealthy houses of Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries. Since then, Owning an antique or any testimony from the classical era would become synonymous with status and intellectuality. It is precisely from here (from these private collections) that the museums that we all know emerged, many centuries later.

Ciriaco of Ancona, nicknamed Antique by his contemporaries for obvious reasons, he died of unknown causes in Cremona, in 1452, just a year before the Ottomans conquered Constantinople and the last vestige of the Roman Empire disappeared forever.