The stage of formal operations is the last one proposed by Jean Piaget in his Theory of Cognitive Development. At this stage, adolescents present a better capacity for abstraction, more scientific thinking and a better ability to solve hypothetical problems.

Below we will see in more depth what this stage is, at what age it begins, what its characteristics are and what experiments have been done to confirm and refute Piaget’s statements.

What is the formal operations stage?

The formal operations stage is the last of the four stages proposed by the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget in his Theory of Cognitive Development the other three being the sensorimotor, preoperational and concrete operations stages.

Formal operational thinking manifests itself from the age of 12 and extends to adulthood, characterized by the fact that children, almost adolescents, have a more abstract vision and a more logical use of thought. They can think about theoretical concepts.

It is during this stage in which the individual can handle hypothetico-deductive thinking, so characteristic of the scientific method.

The child is no longer chained to physical and real objects in order to reach conclusions, but now you can think about hypothetical situations, imagining all types of scenarios without needing to have a graphic or palpable representation of them. This way the teenager will be able to reason about more complex problems.

Characteristics of this stage of development

This stage, which, as we have already mentioned, begins between the ages of 11 and 12 and lasts until we are past adolescence, has the following characteristics.

1. Hypothetico-deductive reasoning

Another name that Piaget gave to this stage was “hypothetico-deductive reasoning.”, since this type of reasoning is essential during this period of development. Children can think of solutions based on abstract ideas and hypotheses.

This is observable by seeing how frequent questions like “what happens if…” are common in late childhood and early adolescence.

Through these hypothetical approaches, young people can reach many conclusions without having to rely on physical objects or visual supports. At these ages They are presented with a gigantic world of possibilities to solve all kinds of problems This gives them the ability to think scientifically, posing hypotheses, generating predictions and trying to answer questions.

2. Troubleshooting

As we have mentioned, it is at these ages that more scientific and reflective thinking is acquired. The individual has a greater capacity to address problems in a more systematic and organized manner, ceasing to limit itself to the trial and error strategy. He now poses hypothetical scenarios in his mind wondering how things might evolve.

Although the trial and error technique can be helpful, obtaining benefits and conclusions through it, the Having other problem-solving strategies significantly expands the young person’s knowledge and experience Problems are solved with less practical methods, using logic that the individual did not have before.

3. Abstract thinking

The previous stage, that is, the concrete operations, the problems were necessarily solved by having objects at hand to be able to understand the situation and how to solve it.

On the other hand, in the formal operations stage, children can work from ideas that are only in their heads. That is, they can think about hypothetical and abstract concepts without having to experience them directly beforehand.

Difference between the stage of concrete operations and that of formal ones

You can even see if a child is in the concrete operations stage or the formal operations stage by asking them the following:

If Ana is taller than her friend Luisa, and Luisa is taller than her friend Carmen, who of all of them is taller?

Children in the concrete operations stage need some type of visual support In order to understand this exercise, such as a drawing or dolls that represent Ana, Luisa and Carmen and, thus, be able to find out who is the tallest of the three. Furthermore, according to Piaget, children at these ages do not have problems arranging objects based on characteristics such as length, size, weight or number (seriation), but they do have a harder time with tasks in which they have to order objects. people.

This does not happen in older children and adolescents, who are already in the stage of formal operations. If you ask them who is the tallest of the three, without having to draw these three girls, they will know how to answer the exercise. They will analyze the phrase, understanding that if Ana > Luisa and Luisa > Carmen, therefore, Ana > Luisa > Carmen. It is not so difficult for them to do serialization activities regardless of whether what they have to organize are objects or people.

Piaget’s experiments

Piaget made a series of experiments to verify the hypothetico-deductive reasoning that was attributed to children over 11 years of age The simplest and best known to verify this was the famous “third eye problem”. In this experiment, children and adolescents were asked, if they had the option of having a third eye, where they would place it.

Most of the 9 year olds said they would put it on their forehead, right above the other two. However, When asking children 11 years old and older, they gave very creative answers, choosing other parts of the body to place the third eye. A very common response was to place that eye in the palm of the hand, to be able to see what was behind the corners without having to look too far, and the other was to have that eye on the back of the head or behind the head, to be able to see. who was behind following us.

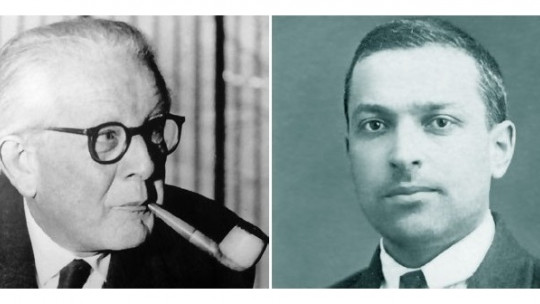

Another well-known experiment, carried out together with his colleague Bärbel Inhelder in 1958, was the pendulum experiment. This consisted of presenting the children with a pendulum, and they were asked what they believed were the factors that influence the speed of its oscillation: length of the rope, weight of the pendulum and the force with which it is propelled.

The experimental subjects had to try to see if they could discover which of those three variables was the one that changed the speed of movement, measuring this speed in how many oscillations it made per minute. The idea was that they should isolate different factors to see which of them was correct with only the length being the correct answer, since the shorter it is, the faster the pendulum will move.

The younger children, who were still in the concrete operational stage, tried to solve this activity by manipulating several variables, often at random. On the other hand, the older ones, who were already in the stage of formal operations, sensed that it was the length of the string that made the pendulum, regardless of its weight or force applied to it, move faster.

Criticisms of Piaget

Although the findings made by Piaget and Inhelder were useful, as were their statements regarding the other three stages proposed in their Theory of Cognitive Development, The formal operations stage was also the subject of experiments to refute what was known about it

In 1979 Robert Siegler conducted an experiment in which he presented several children with a balance beam. In it he placed several discs at each end of the center of balance, and changed the number of discs or moved them along the beam, asking his experimental subjects to predict where the balance would tilt.

Siegler studied the responses given by 5-year-old children, seeing that their cognitive development followed the same sequence that Piaget had proposed with his Theory of Cognitive Development, especially in relation to the pendulum experiment.

As the children got older, they took more into account the interaction between the weight of these discs and the distance from the center and that it was those variables that allowed the equilibrium point to be successfully predicted.

However, the surprise came when he did this experiment with adolescents between 13 and 17 years old. Contrary to what Piaget had observed, at these ages there were still some problems regarding hypothetico-deductive thinking, some of them having problems knowing which way the balance would tip.

This made Siegler suppose that this type of thinking, rather than depending on the maturation stage, It would depend on the individual’s interest in science, their educational context, and ease of abstraction