We all know that art, like so many things, is subjective. However, Is there one art that is objectively better than another? Can we find an artistic style or a time in which its artistic manifestation is, objectively, better than the others?

We propose a walk through the history of art to unravel if there really is an art that is objectively better than another.

Is there objectively better art?

During some periods of history this has certainly been believed. This is why, during the Renaissance, authors like Vasari disparaged Gothic art and called it “barbarous” art (goth art, which is where its name comes from). The Baroque was also another of the styles that was highly maligned with the advent of the French Revolution and classicism. But what reason was there for these considerations?

The reason was none other than the change in mentality and, therefore, the appearance of prejudices. By Vasari’s time, the Renaissance had taken over the arts, so anything that did not fit a “classicist” vision was considered a minor, less evolved art. The same thing happened centuries later with the Baroque and, especially, the Rococo. The French revolutionaries saw the latter as the art of the nobility and, therefore, an art that must be destroyed.

So To what extent are artistic evaluations subject to bias?

But what is art, exactly?

Here we need to introduce a clarification. What is the art? A definition as multiple as it is complex (and complicated). The Royal Spanish Academy offers various definitions of the word. Among them are the following: “Capacity, ability to do something,” and “Manifestation of human activity through which what is real is interpreted or what is imagined is captured with plastic, linguistic or sound resources.” We believe that, in the second meaning, the RAE has hit the nail on the head. Let’s look at it carefully: “… through which what is real is interpreted or what is imagined is captured.” It is clear: art has two ways: the representation of reality (sometimes, strictly, as we will see later) or the expression of transcendent concepts. Furthermore, we must add that both things are not incompatible with each other, although they make us believe so.

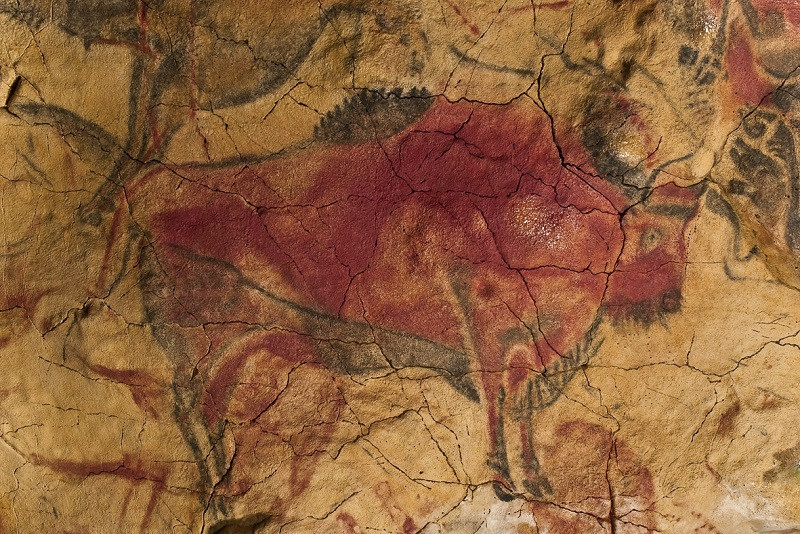

For his part, the eminent E. H Gombrich, in his famous The history of art, begins his introduction by asserting that: “Art does not really exist. There are only artists. These were once men who took colored earth and roughly drew the shapes of a bison on the walls of a cave; Today, they buy their colors and draw signs for the subway stations.” And then he adds: “There is no harm in calling all these activities art, as long as we keep in mind that Such a word can mean many different things, in different times and places and as long as we notice that Art, written with a capital letter A, does not exist, since Art with a capital letter A has by essence to be a ghost and an idol…”.

In other words, for the prestigious historian, if only artists exist and, therefore, there is no ideal of art (that Art with a capital letter that he comments on), then it means that, effectively, there is no better or better artistic style or era. worse than others. To make this brief journey, it will be very helpful to rely on specific examples; In this way it will be much easier to understand what Gombrich meant by such a statement.

The composition, the form, the perspective

Let’s take the bison that Gombrich comments on as an example. You all have in mind the typical prehistoric painting, made in the shelter of a cave. Let’s ask a question. Is this representation realistic? Do not hesitate to answer, because the answer is “no”.

The artist who painted the bison did not intend to depict a real bison , with its volumes, its perspective and its realistic details. In effect, there is no perspective; The drawing is completely flat (although, in some examples, accused attempts at realism can be noticed). In any case, the result is the same: the animal depicted on the wall or ceiling of the cave represents an idea, a concept, not a real bison.

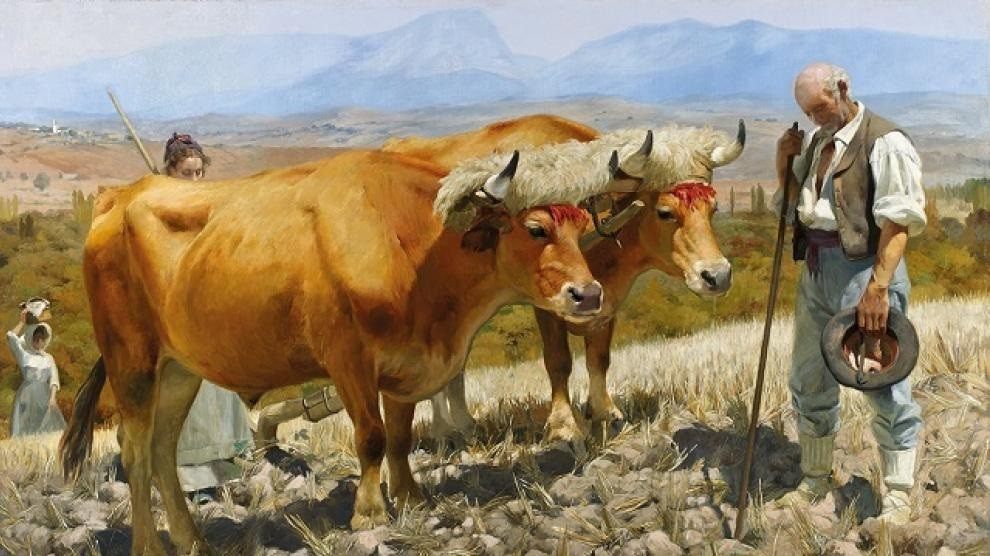

Let’s compare the prehistoric bison with a 19th century painting; For example, Angelus prayer in the fieldby the Vitorian painter Ignacio Díaz Olano.

We will observe that, on the canvas, the painter has made a detailed, practically photographic representation , from the anatomy of two oxen. The volumes are perfect, the perspective is adequate; We have the feeling of being present in the scene, as if we were part of the instant represented. In a word: Díaz Olano is capturing a fragment of reality.

At this point, we ask a question. Is Díaz Olano’s painting objectively better? In terms of resolution, drawing, perspective and technique, of course yes. The perspective, the volumes, the realistic tones of the painting; They have nothing to do with the flat figure, of neutral colors, that we saw on the wall of the cave. Now, does this mean that Díaz Olano’s work is objectively better, in general, than the prehistoric bison? The answer, in this case, would undoubtedly be “no”.

The expression, the concept, the idea

Let’s take another example that will illustrate very well what we mean. And it is none other than The May 3 shootings by Goya.

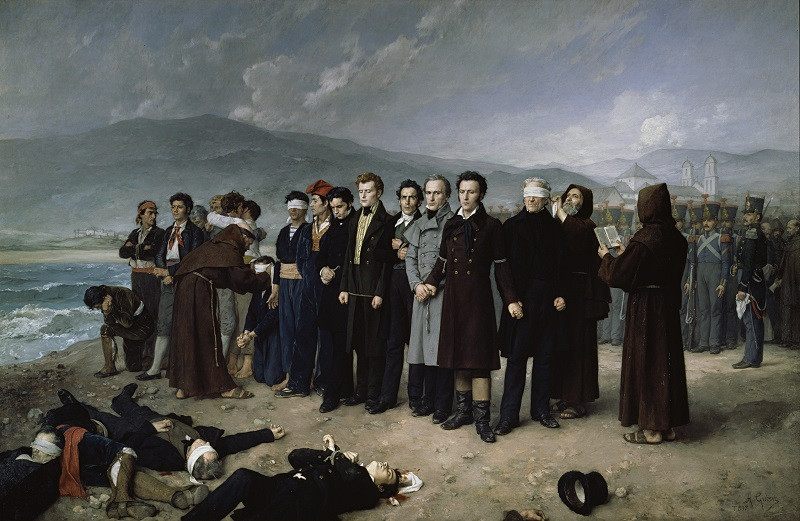

Good. Let us now compare it with another execution scene: Execution of Torrijos and his companions on the beaches of Malaga by Antonio Gisbert.

Let’s start with the second. In Torrijos, everything is perfect. Again, the composition has no flaws; nor the perspective, nor the volumes, nor the drawing, nor the technique. It is, formally speaking, a perfect picture. Furthermore, Gisbert also introduces expression into his work: if we look closely, each of the faces of those who are going to die express a different feeling, ranging from the most atrocious fear to the most surprising serenity.

Let’s now go to the Goya executions. Can we say that, formally, Torrijos’ case is better resolved? Well, despite talking about Goya, the answer is again “yes”. Gisbert’s canvas is a photographic snapshot , capturing a real moment in life. Again, and as happens with The Angelus by Díaz Olano, it seems that we are on the beach, with Torrijos and his companions. In fact, what is really exciting about the painting is that it seems that we are part of the group of prisoners waiting their turn to die, given the point where the viewer’s view is located. As for the faces, nothing more to say; Gisbert took notes on original portraits of the victims, and also interviewed relatives of the deceased to faithfully recreate the features of the executed.

Now, if we go to Goya’s painting, we will see that the faces are not identifiable. To begin with, the French (the executors) hide their faces, as if they were ashamed. Furthermore, the majority of those shot cover their faces with their hands. The few that show their faces seem to us, more than human beings, to be Carnival masks, or nightmare masks. There are no individualized factions; Goya is painting terror in its purest form.

So let’s get to the question. Does this mean that Gisbert’s painting is objectively better than Goya’s? Obviously not. And because? Because, simply, Gisbert’s intention when making his Torrijos was not the same as Goya’s when he painted his Executions. The first wanted to show an impeccable reality, while the second He expressed his anger and frustration through the brush Gisbert did not experience the execution of Torrijos; In fact, he painted the painting several decades later. Goya did live those fateful days of May.

The burden of Academicism

From the 18th century and, above all, in the 19th century, academic art (such as the painting of Torrijos) is considered the zenith of painting and sculpture. The perfect composition, the resolution of a seamless perspective, the correct proportion between characters… academic works do not, in fact, have any formal errors to point out

However, it is no less true that during the 19th century the expression and the idea were forgotten. In other words, the “what” was diluted, and only the “how” remained. Very contrary to what other “arts” in history had been, where what had prevailed above all else was the concept, the idea that was represented. This is one of the reasons why, among others, medieval art was largely disparaged since the 18th century; His conceptual, transcendent style did not fit with the prevailing academicism

If we want to correctly value a work of art, we must keep in mind that in our appreciation we carry the burden of Academicism. And be careful, because we do not mean with this that academic art is bad, on the contrary; But it is true that for many years we have been taught that the only “good” art is that which respects the formal guidelines of perspective, volume and composition, among other things. And this, of course, causes us to lose our way and not be in a position to value the other “arts” which, of course, have value in themselves.

Because the guidelines needed to evaluate a work are not only those that the Academy has been dictating to us for centuries. There are others, such as expressiveness, feeling and idea which, on the other hand, are what dictated the art of other times and cultures. Should we believe that a Romanesque Virgin and Child is “worse” than a Venus of Praxiteles? Of course not. They are daughters of two concepts and two very, very different worlds.

However, and like everything related to art, the decision is up to each individual. In this article we only propose a different look and, above all, appropriate for each specific work; a look that takes into account the context, the technical possibilities and the personality of the author.