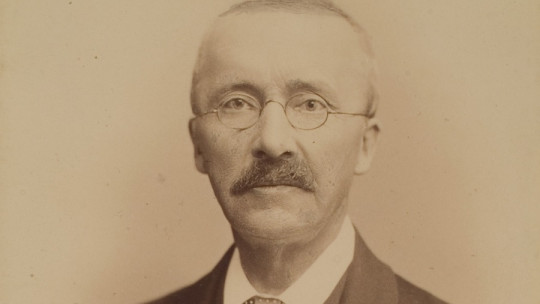

Since Winckelmann was never an archaeologist, the nickname by which he is known may be a bit of an exaggeration. However, it makes sense. And the person we are talking about today laid the foundations for the history of art and the classification and study of archaeological objects, which is why all scholars of the past owe him, to a certain extent, their profession.

Greatly passionate about classical antiquity (and, more specifically, his beloved and idealized Greece), Winckelmann directed his steps, from his most tender youth, to what really gave meaning to his existence: recovering from oblivion all the beauty of a past. in which he considered that all artists had to look at themselves if they wanted to achieve perfection. Today we talk about what is called “father of modern archaeology”: Johan Joachim Winckelmann.

Brief biography of Johan Joachim Winckelmann, the great pioneer

And it was in many ways. When Johan Joachim was born, on a cold December day in 1717 (in Stendal, a small town with a more than prophetic name, then belonging to the Margraviate of Brandenburg), classical antiquity was already in fashion, but no one took it seriously enough.

We explain ourselves. Although the collecting fever for artistic objects dated back many centuries, it was still a pastime with which aristocrats and petty bourgeois competed with their neighbors and decorated the sumptuous galleries of their palaces. But No one had bothered to properly catalog all those treasures. In other words: art history or archeology as such did not yet exist.

The first steps of an enthusiast

In this eminently enlightened context, little Winckelmann was born, into a family that, however, was of very humble origins (his father was a shoemaker). Thanks to the interest of some of his teachers, who paid for his studies, the young man was able to enter the Berlin Lyceum at the age of seventeen. His interest in antiquity, which he had been showing since he was a child, was spurred by his access to the study of the classics, which I would never abandon. In fact, from 1734 to 1738 we find him at the Salzwedel Institute in Brandenburg, where he dedicated himself fully to discovering and analyzing Greek culture.

To please his family, Winckelmann enrolled in Theology at the University of Halle, where he only completed the first two years. He soon realizes that this is not for him, and he moves to the University of Jena to study Medicine, where he only stays for one year. The university experience, however, has allowed him to get even closer to authors such as Epictetus and Plutarch, in addition to introducing him to other authors such as Joachim Lange (1670-1744), one of the precursors of Pietism, a religious current within the framework Lutheran.

To support himself during all these years of studies, Winckelmann has needed to work as a teacher. In 1743 we find him in Seehausen, working as a school teacher, an activity that would bring him a lot of tedium and that only his continuous studies of the classics in his spare time would help alleviate.

Greece as beginning and end

At 37 years old, Johan Joachim Winckelmann is a true scholar of classical culture. His extensive cultural background in this sense drives him to create what will be his first work, Reflections on the imitation of Greek works in painting and sculpturewhich came out in 1755 and was an international success. In his work, Winckelmann reflects on the role of Greek art in the future of universal art a role that he considers main, if not only, on the path to perfection.

As the art historian Miguel Ángel Elvira Barba points out in the conference he gave about Winckelmann and the Herculano excavations (see bibliography), the Reflections… are the “catechism” of the recently released Neoclassicism, which will have precisely in its author his great prophet.

And, in reality, Winckelmann is the “inventor” of classical Greece that we all know. When we say that he “invented” it, we do not mean, of course, that it did not exist, but rather that the vision that Winckelmann gave to the world of Greek culture is very different from what actually constituted it. We are facing the typical case of idealization of an era that, in this case, had a very deep impact on European society, to the point of unleashing a real fever for everything “Greek” and “Roman.” The fever even spread to fashion, since, at evening parties, ladies appeared dressed in clothing that imitated the tunics of classical goddesses. A good example of this was Lady Emma Hamilton, whose performances in Naples, imitating the postures of classical sculptures, caused a real sensation.

Greece is, therefore, for 18th century European society and for Winckelmann specifically, the beginning and the end of everything. According to our character, with Greek art artistic plenitude is achieved, as well as maximum beauty, and nothing that is done next can be compared to it, unless it imitates “Greek perfection.” When, at the end of 1755 (and by virtue of a generous scholarship), Winckelmann arrived in Rome, he was enraptured by the Apollo of Belvedere, kept among the numerous treasures of the Vatican and which he considered the summation of ideal beauty.

And Winckelmann had wanted to go to Rome for a long time; but not, as one might think, to admire Roman culture, but to seek in it the vestiges of that Greece that he admired so much. For our intrepid historian, Rome was nothing but decadence, the time of “imitations” of the Hellenic beauties, a period that, precisely for this reason, immediately went into the background.

A brilliant career in the Vatican

To travel to Rome and, above all, to be able to delve into the Vatican collections without problems, an acquaintance recommended Winckelmann convert to Catholicism, which he did without a moment’s hesitation. Thus, just the year in which his magnum opus came to light, the aforementioned Reflectionsour character arrives in the Eternal City with a scholarship of 200 bags under his belt (courtesy of the Prince Elector of Saxony, his great friend and admirer).

In Rome, Winckelmann will make a great friendship with Anton Rafael Mengs (1728-1779), the famous 18th century painter who portrayed great kings and queens. The artist was in Rome to learn about the classics and perfect his technique, and the two became great friends. In the meantime, he has been offered the position of Vatican librarian, given his extraordinary culture, which he accepts without hesitation. Winckelmann’s dream has come true: he will finally be able to delve into hundreds of classical texts and further refine his great knowledge of antiquity.

Three years later he traveled to Herculaneum, in Naples, ready to admire the remains that are emerging from the ancient city buried by Vesuvius. The discovery, made by a farmer who was digging to find water, went around Europe. An underground Roman city! Soon the first treasures began to appear, among them, the famous Herculaneses, delightful sculptures that Winckelmann called “vestals” and which were transferred to Vienna.

Winckelmann would still return to Herculaneum a couple more times. However, His ability to travel was limited after his appointment as prefect of antiquities of Rome, a position received directly from the pope for which Winckelmann was forced to profess as a priest. We do not believe that he had any problem doing so, since, in reality, the only thing he was interested in was being in contact with that ancient world to which he so longed to return.

Neoclassicism or classical idealization

We have already commented that Winckelmann’s Reflections are a kind of “bible” of Neoclassicism. In this book and in the rest of his work (also famous is his History of the Art of Antiquity, published in 1764) Winckelmann promotes the image of an ideal Greece, based on virtue and beauty. Some historians, as the aforementioned Miguel Ángel Elvira Barba comments, suggest that The writer transferred Rousseau’s “noble savage” myth, so fashionable at the time, to Ancient Greece. In any case, this idealization reached all of Europe, and everyone began to dream of antiquity as if it were the beautiful lost paradise.

Of course, as an art historian, Winckelmann makes numerous mistakes, including the belief that the Greeks sculpted their statues from the purest white. It is well known that, like all ancient peoples, the Greeks polychrome their sculptures and buildings, and that that immaculate white that has survived to this day is only the result of many centuries of deterioration, which has made the entire pigmentation.

In any case, this is how classical Greece was read in the 18th century, and this is how neoclassical artists such as Antonio Canova (1757-1822) or Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) picked it up. But, although it is true that Johan Joachim Winckelmann read the testimony of history “badly”, it is no less true that he was the great promoter of the history of art as we know it today, and his work in this sense must be valued. as it deserves.

His tragic death is a sudden curtain that fell too quickly, just when he was at the peak of his fame. Winckelmann had traveled to Austria to receive the honors of the empress herself, when, in an inn in Trieste (about to return to his beloved Italy), he was stabbed to death by an individual who was spending the night in the same hostel. Apparently, Winckelmann had been imprudent enough to show him the treasures he had with him… It was the year 1768, and the art historian was only fifty years old. Behind him he left a trail that permeated the entire 18th century and that would only begin to crack with the arrival of turbulent Romanticism.