The philosophy of language is one of the most interesting currents born in modern philosophy and one of its great representatives is the protagonist of this article.

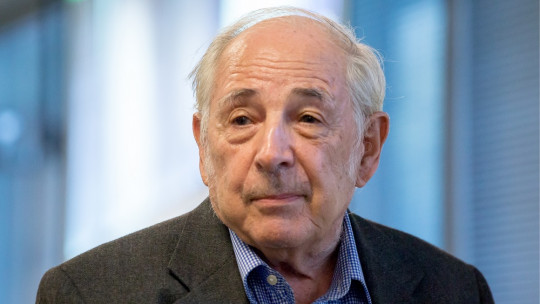

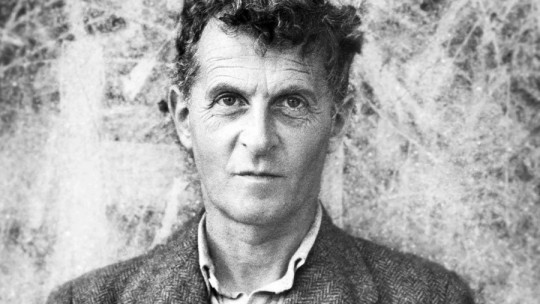

John Langshaw Austin He is, perhaps, the greatest of philosophers of language along with John Searle, Noam Chomsky and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Born and raised in the United Kingdom, he is one of the authors, along with Searle, of the theory of speech acts, providing the three main categories to the way in which human beings utter our sentences.

His life, although brief, has been one of the most influential in his field. Let’s take a deeper look at his interesting story throughout this John Langshaw Austin biography

John Langshaw Austin Biography

The life of this philosopher of language is neither characterized by publishing prolifically nor, unfortunately, by having lived many years. Even so, this British thinker knew how to take advantage of the years of his life, being the creator of one of the most important theories in the field of psycholinguistics in addition to having received a few awards.

1. Early years and training

John Langshaw Austin was born in Lancaster, England, on March 26, 1911.

In 1924 he enrolled at Shrewsbury School, where he studied the great classics of all time. He would later study classical literature at Balliol College, Oxford, in 1929.

In 1933 He received degrees in classical literature and philosophy, as well as the Gaisford Prize for Greek Prose He finished those studies being the first in the class. In 1935 he began teaching at Magdalen College, also in Oxford. Later he would enter the field of Aristotle’s philosophy, being a great reference throughout his life.

2. Formation of your thinking

But among his earliest interests was not only Aristotle (later, between 1956 and 1957, Austin was president of the English Aristotelian Society). He also addressed Kant, Leibniz and Plato. As for his most influential contemporaries, GE Moore, HA Prichard and John Cook Wilson can be found.

The vision of the most modern philosophers shaped their way of seeing the main questions of Western thought and it was from this moment on that he began to take special interest in the way human beings make specific judgments.

During World War II, Austin served his country working in British Intelligence. In fact, it has been said that He was one of the most responsible for the preparation of D-Day, that is, the Normandy Landings

John Austin left the army with the rank of lieutenant colonel and was awarded the Order of the British Empire, the French War Cross and the American award of the Legion of Merit for his work in intelligence.

3. Recent years

After the war, Austin He worked at Corpus Christi College, Oxford as a professor of moral philosophy

During his lifetime, Austin was not particularly prolific in terms of publications (he only published seven articles), however, this did not prevent him from becoming famous. His influence was due, mainly, to the fact that he held very interesting conferences. In fact, he became famous for giving some of them on Saturday mornings, something that for a teacher of the time was quite striking.

Thanks to this, and the increase in his popularity, John Austin visited universities such as Harvard and Berkeley in the 1950s.

It is from these trips that the material to write arises. How to do things with words a posthumous work that collects, in essence, his entire philosophy of language. Also It was during these years that he had the opportunity to meet Noam Chomsky becoming very good friends.

Unfortunately for the world of linguistics, John Langshaw Austin died at just 48 years of age, on February 8, 1960, shortly after being diagnosed with lung cancer.

Philosophy of language and its method

Austin had little satisfaction with the way philosophy was being carried out in his time, especially with logical positivism. According to this author, logical positivism was responsible for producing philosophical dichotomies that, instead of making things clear and helping to understand the world around us, seemed to oversimplify reality and tended towards dogmatism.

Austin developed a new philosophical methodology, which would later lay the foundations of philosophy based on ordinary language John Austin did not consider this method to be the only valid one, however, he did seem to bring Western philosophers closer to the resolution of long-standing questions such as freedom, perception and responsibility.

For Austin, The starting point had to be analyzing the forms and concepts used in mundane language , and recognize their limitations and biases. This would allow us to reveal those errors that have been made since time immemorial in philosophy.

According to this author, in everyday language we find all the distinctions and connections established by human beings. It is as if words had evolved through natural selection, surviving those most adapted to the linguistic context and those that allow us to describe the world that human beings perceive. This would be influenced by each culture, expressing itself in a different way of seeing things.

Speech act theory

Speech act theory is surely John Austin’s best-known contribution to the field of philosophy of language. Speech act theory is a theory of how communicative intentions are manifested In this theory, the concepts of intention and action are incorporated as fundamental elements of the uses of language.

In their time, most philosophers were interested in how formal language worked, that is, one that is formed with logical rules. An example of formal language would be the following: mammals suck, dogs suck, therefore, dogs are mammals. However, Austin chose to describe how everyday language is used to describe and change reality.

One of the most interesting aspects of Austin’s interest in ordinary language was his realization how, depending on what is said, it is possible to create a situation in itself That is to say, there are expressions that, when emitted, are in themselves what they are describing what is being done. To make it better understood:

While at a wedding, the priest who officiates the ceremony, after the bride and groom have given each other the rings, says out loud: ‘I hereby declare you husband and wife.’ By saying ‘I declare’ the priest is not describing a reality, he is creating it. Through his words he has made two people, officially, a marriage. And this has been accomplished through a speech act, in this case, a statement.

Thus, speech acts are understood as those linguistic expressions, both oral and written, that when emitted imply a change in reality by themselves, that is, they are what they say they are doing.

Within Austin’s theory, with speech act, a term that was originally used by John Searle and Peter Strawson, reference is made to statements that constitute, by themselves, an act that implies some type of change in terms of the relationship between interlocutors as has been seen in the case of the wedding.

Within the same theory, John Austin distinguishes between three types of acts:

1. Locutory speech acts

They are simply saying something. It is what the act of a human being saying or writing something is called, regardless of whether it is true or not or whether it constitutes in itself a change in reality.

2. Illocutionary speech acts

They are acts that describe the speaker’s intention when uttered For example, a case of an illocutionary act would be to give congratulations, which in itself implies doing an act, which is to congratulate.

3. Perlocutory speech acts

They are the effects or consequences that arise from the act of emitting an illocutionary act, that is, the response of having said something, whether it is a congratulation, insult, order…

They are acts carried out for the sake of stating something They reflect the result of an act enunciated by the speaker which has produced an effect on the listener.

It is not enough to recognize the speaker’s intention, but the recipient must also believe it. They are not executed simply by stating them.