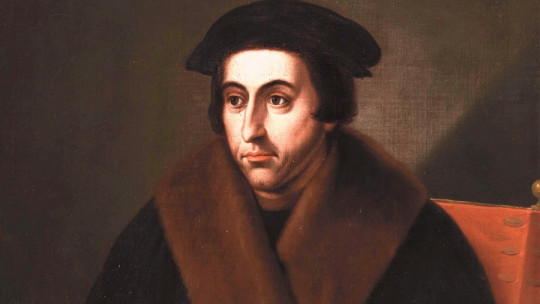

Considered one of the greatest humanists of Renaissance Europe, the life of Juan Luis Vives was long forgotten. Philosopher, philologist, pedagogue and, in a certain way, psychologist Vives was a man of extensive knowledge and many concerns.

Trying to save himself from the yoke of the Inquisition, he fled to England and Flanders, places where he had the opportunity to rub shoulders with the highest echelons. His advice and words full of wisdom reached the ears of monarchs such as Charles V, Francis I, Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon.

Juan Luis Vives maintained a close relationship with other great Renaissance figures such as Erasmus of Rotterdam and Thomas More and, here, we are going to delve a little deeper into his personal history, in addition to his extensive repertoire of works, through a biography of Juan Luis Vives

Brief biography of Juan Luis Vives

Juan Luis Vives (in Valencian Joan Lluís Vives and in Latin Ioannes Lodovicus Vives) was born in Valencia on March 6, 1493 into a family of converted Jews. Although the family had left their Hebrew creeds behind, he could not save himself from the religious persecution of his time, being cruel to the Vives.

Early years and flight from Spain

From a young age, Juan Luis Vives had to face bad news when he discovered that His cousin Miguel was accused of having worked as a rabbi in a clandestine synagogue To prevent these same problems from pursuing him, when he had the opportunity, Juan Luis Vives fled abroad.

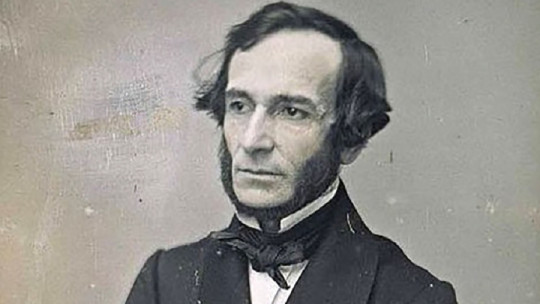

Having already studied in Valencia, he ended up at the Sorbonne in Paris. In 1512 he settled in Flanders where he was a professor at the University of Louvain and established a close relationship with Erasmus of Rotterdam.

In 1524, his father, Luis Vives, was sentenced to burn at the stake. Her sisters claimed the dowry from her mother, Blanca March, a relative of the famous Valencian-language poet Ausiàs March. Her mother had died several years ago but, even so, the Holy Inquisition managed to accuse her of heresy, exhuming her corpse and turning it into food for the flames. Everything was valid to keep the confiscated money.

Being abroad received an offer to return to Spain and teach at the University of Alcalá de Henares However, seeing how his country was treating his family, it is not difficult to understand why he decided to reject these types of offers. By then he had already settled in England, a place where the dark shadow of the Inquisition did not have as much force, and he lived well off the fame he had earned. He taught at Oxford University’s Corpus Christi College.

Counselor to the kings of England

His prestige as a man of extensive knowledge opened many opportunities for him, allowing him to rub shoulders with the highest English aristocracy. He became a figure very close to Queen Catherine of Aragon and also became close to the politician and humanist Thomas More

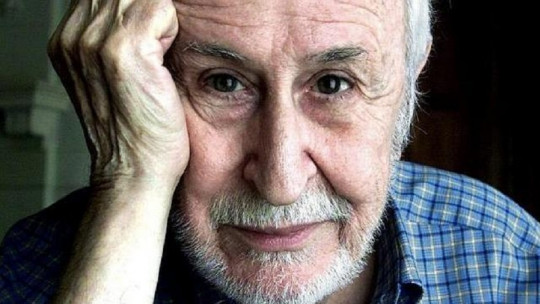

His friendship with Moro occurred just in difficult times. These intellectuals were united by common concerns, since both believed that humanism had gone into decline due to its own representatives, now concerned with political interests.

In 1526, After staying briefly in Bruges, Flanders, he wrote his Poor Relief Treaty It is a text in which it advocates a vision of assistance to the most disadvantaged, defending that the public administration must do everything possible to improve the quality of life of the people who live on its lands. The ideas he presents in this text are considered the precursors of social services in Europe.

Leaving England and final years

Upon his return to England, thanks to the favor he enjoyed at court, He earned the title of Latin teacher of Mary Tudor, future queen of the country But despite the sympathies of the kings, their position was truncated by the political changes that were coming.

Henry VIII asked the Church to be able to separate from Catherine of Aragon since she was not giving him a son, but this request was denied, causing the English monarch to decide to create his own church, the Church of England, in which he was its highest representative.

Vives was not in favor of either the divorce or Enrique’s unilateral decisions, but instead of supporting Catalina he asked her to keep a low profile rather than speak out against her husband’s decisions. Both the king and the queen saw Vives’s non-positioning as a position contrary to their own, which caused him to very quickly lose the favoritism of both monarchs. Consequently, He lost the pension offered by the royal house to survive, and began to worry

Vives, already an expert in fleeing from countries where he was not wanted, saw how the pattern he experienced in Spain was repeated. If in his native land the cruelty of the ecclesiastical authorities was for being Jewish, in England he would be so for not having been openly opposed to the Church. Thomas More had asked Henry VIII to obey the Pope, which led to his execution in 1535. Vives’ fears were not unfounded and, after the death of his friend, he decided not to return to England.

His last years were spent in Flanders. There he dedicated himself to moral philosophy and pedagogy, in addition to delving deeply into the need for the European peoples to unite in peace and harmony, but fighting bellicosely against the Muslim enemy. Juan Luis Vives would die on May 6, 1540 in the Flemish city of Bruges after having experienced the last ravages of very poor health, despite only being 47 years old.

Thought and work

The work and thoughts of Juan Luis Vives are truly attractive, since they are those of a humanist, Renaissance man, defender of a common European identity , Catholic-based, to confront Islamic threats. He saw Christianity split again, this time into Catholics and Protestants. In a world in which the scepter and the throne went hand in hand, any change in the way religion was interpreted implied a political change.

Although at first he believed that the break between the Church of England and the rest of the Christian world would simply be a theological dispute, the events experienced by Thomas More and himself quickly changed his mind. That is why, Far from firmly defending the unilateralism of the rulers and the Pope, Vives defended that Christian kings should unite as brothers, in peace and harmony , to make the continent progress. He used the term Europe not to refer to the region, but to its civilization.

He believed that in the schism of England and the papacy, their sovereigns should speak to reach a common position. The problem had to be solved through words and dialogue, not by using the sword. Thus, Juan Luis Vives shows a true democratic, conciliatory spirit, something that would sow the will of later councils that would try to remove iron from the “betrayal” of the English Christians.

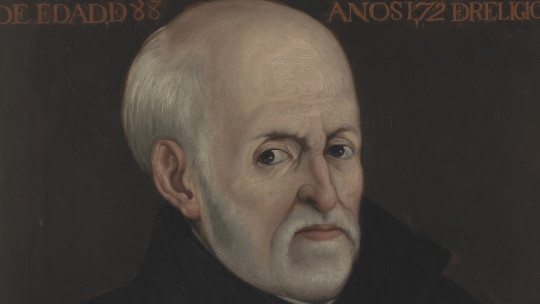

He was critical of how many Catholics lived their faith. In a letter addressed to Pope Alexander VI, better known as Rodrigo de Borja (or Borgia) and a Valencian like himself, Vives expressed his concern about how Sunday masses had become an almost parodic representation of what Christians owed. do and did not do. Charity was promoted, but it was not done; Understanding and peace were promoted, but kings and religious people engaged in absurd fraternal wars.

Regarding his way of teaching and more academic thinking, Vives tried to recover Aristotle’s thought, leaving aside medieval scholastic interpretations , in addition to being a promoter of ethics inspired by Plato and the Stoics. He was an eclectic and universalist man who advanced innovative ideas in multiple philosophical, theological, pedagogical and political subjects. His total writings amount to sixty and he wrote them entirely in Latin. In all of them he insists that teaching should be based on problems of methods rather than giving a master session.

He understands the student’s mind, which is why he has been considered a great pedagogue and psychologist. In his treatise “On the Soul and Life,” although he follows Aristotle and defends the immortality of the soul, he attributes the empirical study of spiritual processes to psychology. He studies the theory of affects, memory and the association of ideas, for which he is considered the precursor of 17th century anthropology and modern psychology.

Another of her pedagogical works that stand out is “Institutione de feminae christianae” (1529), a kind of ethical-religious manual aimed at the good Christian woman, whether young, married or widowed. We also have “De ratione studii puerilis”, which is considered one of the first humanistic education programs. Other books in this same line are “De ingeniorum adolescentium ac puellarum institutione” (1545) and “De officio mariti”, “De disciplinis” (1531), finally, it is divided into three parts: “De causis corruptarum artium”, “ De tradendis disciplinis” and “De artibus”.

As for his more social works, we find several treatises, including “The Relief of the Poor” or “De subventione pauperum” (1526) and “De communione rerum” (1535). In his works, Vives always writes about specific topics and with proposed solutions such as “De conditione vitae christianorum sub Turca” (1526) or “Dissidiis Europae et bello Turcico” (1526), works in which he addressed the problems of Christianity in relation to the Turks and the Protestant Reformation, defending the idea stated that Europeans were to unite against the Muslims, especially the Ottomans.

Linked to his reputation as a good connoisseur of the Latin language we have his “Linguae latinae exercitatio” or “Latin language exercises” (1538), a book with dialogues full of great simplicity that he dictated to facilitate the learning of Plutarch’s language among his students.