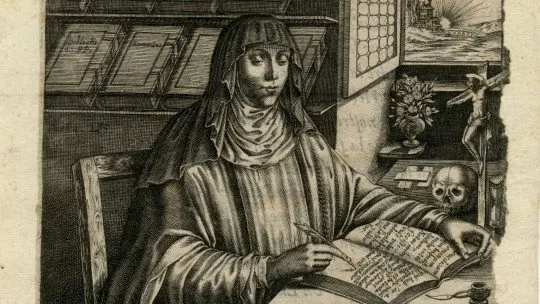

Many things have been said about Lucrezia Borgia: that she was frivolous and lustful, that she committed incest with her brother and her father, that she promoted a series of murders and that it was even she herself, with a powerful poison, who carried them out… Nothing more than a black legend, spurred on by its enemies and by historical distance. Lucrezia Borgia (1480-1519) had the misfortune of being born into a very powerful family.

From a very young age he became the pawn of his father, Pope Alexander VI, who, through a series of marriages (which he undid at his convenience, depending on his political interests) forever linked his only daughter to the political future of the Borgias and the papacy. Lucrecia was nothing more than a victim. Today we talk about the daughter of Pope Alexander VI and we review the sad life of this woman, unjustly attacked by the black legend: Lucrezia Borgia.

Brief biography of Lucrezia Borgia, the unfortunate daughter of Pope Alexander VI

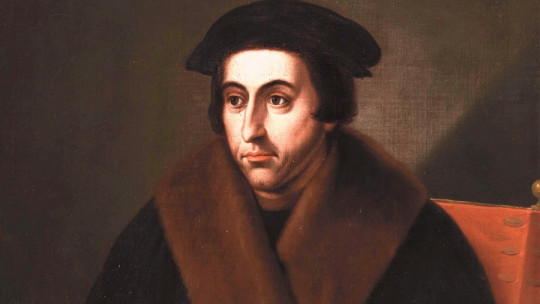

Much of this black legend was forged after the annulment of her first marriage to Giovanni Sforza. When the union no longer had any political advantage for Alexander VI, he proceeded (as pope) to annul the marriage, under the pretext that it had not been consummated. Humiliated, Giovanni began to spread the rumor that his ex-wife was a lustful who had even slept with her own father.

What is true in these words? Is it true that Lucrezia had relations with the pope, as well as with her brother Caesar? There is no reliable testimony, beyond malicious rumors, to substantiate such an accusation. But let’s start at the beginning. Who was Lucrezia Borgia and why was she so important on the Italic chess board?

The dad’s daughter

When Lucrezia was born, on April 18, 1480, her father, Rodrigo Borgia, was not yet pope, but he was a cardinal. The girl was born as a result of her love affair with Vanozza Catanei, who gave the future pope three more children: César, Juan and Jofre.

The Borgias were originally from Xátiva, Valencia. Their original surname was Borja, but later, when they entered the Vatican, they changed the sound to a much more Italianate Borgia. Rodrigo, Lucrecia’s father, was the nephew of Pope Calixtus III, also a Borgia, and thanks to their relationship and the usual nepotism of the time, he soon found himself ordained cardinal.

Vanozza, one of Rodrigo’s lovers (he had many more, who gave him more children) was married to a Vatican official. Retired in Subiaco, a bucolic place a few kilometers from Rome, she gave birth there to Lucrecia, who was raised in the Orsini palace, with a cousin of Rodrigo himself, Adriana del Milà. Later, and as was usual for Renaissance ladies, she was taught by eminent humanists in Greek, Latin, music, dance and poetry, so the young Lucretia became an extraordinarily cultured woman.

In the 15th century it was not at all unusual for ecclesiastical dignitaries to have children. Although since the Gregorian reform of the 12th century these children were considered illegitimate and could not access the goods of the Church, this was not an obstacle for their illustrious parents to grant them high positions (often, at an excessively young age), incomes and, of course, advantageous marriages with the aristocracy and the most important bourgeoisie of the peninsula.

That was the fate of that pale blonde girl, whose first marriage contract was planned when she was only eleven years old, with a Valencian nobleman, Querubín Juan de Centelles. However, the project did not prosper, among other things, because, in 1492, Lucretia’s father had been elected pope with the name of Alexander VI. A “simple” Valencian nobleman was not enough for the pope’s daughter.

The poor chess pawn

From the age of twelve to twenty-one, Lucrecia’s life will be a whirlwind of commitments and marriages orchestrated by her father, the Pope. The supposed “poisoner”, the “scheming” and “lustful” girl was nothing more than a poor chess pawn in powerful hands.

In 1493, a year after her father was elected pope, Lucrezia, only twelve years old, was forced to marry Giovanni Sforza, a member of the powerful family that ruled Milan. In those days, the union was very advantageous for papal interests, since the Duchy of Milan, in addition to being one of the most powerful on the Italian peninsula, represented a stopper for the expansion of neighboring France.

First marriage: annulled

The wedding takes place, but it only lasts a few months. Soon, Alexander VI realizes the mistake. Ludovico the Moor, head of the Sforza family in Milan, is not the perfect ally he had thought. Political interests encourage an alliance towards other paths, so the pope does not hesitate to annul his daughter’s marriage (the marriage that he himself had imposed on her) under the justification that it had not been consummated and that, furthermore, Giovanni Sforza It is “powerless.”

We do not know if this is true or if it was a mere excuse to end a link that was no longer interesting. It seems more plausible to think the latter, since Lucretia, retired to a convent since the annulment, gave birth to a child, Giovanni, whose paternity, despite the fact that evil tongues endeavored to grant Caesar, the young woman’s brother , it seems likely that it was her ex-husband’s. The fact that the young woman was confined to a convent seems to confirm this; If the marriage annulment had been made based on an alleged lack of consummation, a child jeopardized the credibility of the verdict.

The humiliation suffered by Giovanni Sforza, who was forced to sign a document acknowledging his powerlessness, prompted him to make a series of comments that surely lack any semblance of reality. For example, on one occasion he said that “the pope wants to keep from me what he reserves for himself,” implying that Alexander VI had carnal relations with his own daughter. This is the germ of the black legend that hung over Lucrecia and that only grew over the years and as her family gained enemies.

Second marriage: suspicious death

Once Lucretia was freed from her first marriage, Alexander VI looked for another husband who was more in line with her interests. The lucky one was Alfonso, illegitimate son of the king of Naples. It seems that, in this case, the two young people fell deeply in love; They shared tastes and their characters were very compatible. Was it possible that the poor daughter’s happiness could be added to the father’s interests?

Well no. It couldn’t be. Once again, the alliance with the king of Naples faltered. Apparently, the marriage of Lucrecia and Alfonso was just a step towards the big move, which was to marry Caesar (whom Alexander had already removed from the cardinalate) with the king’s own daughter. When the matter did not bear fruit, the pontiff decided that Lucrecia’s marriage to Alfonso should end. On this occasion, it was not possible through an annulment, since the young woman had given birth to a son from her husband…

One night in the year 1500, Alfonso was robbed on the streets of Rome, where he had settled with his wife and son, and brutally stabbed. Still alive, he was transferred to his chambers, where the faithful Lucrecia, probably suspecting a black hand (and quite close) behind the attack, did not leave her bed. She only came out when her brother Caesar (or her father, according to other sources) called her. When she returned, her husband was already dead; According to what they told him, because, when he fell out of bed, a terrible hemorrhage had occurred…

Lucrecia went into a deep depression. Not only did she realize how little her happiness mattered to her own family, but she also realized how far they were willing to go for power. Furthermore, she had sincerely loved Alfonso, the only one who had given her a little joy and love in her sad existence. Destroyed, she secluded herself in Napi Castle and painted the walls of her rooms black. She didn’t want to know anything about her father or her brother.

Third marriage and a well-deserved peace

Naive Lucrecia! She was the pope’s daughter. She could not dream of a life of seclusion and peace. Soon, she was convinced by the pontiff to abandon her confinement and marry (again!) for the sake of her family. The lucky one was Alfonso d’Este, belonging to the powerful family that ruled Ferrara. Lucrecia went to the court of this city, and there began what would be the most stable and peaceful period of her life. Finally (and forever) away from her intriguing family, and despite the fact that her new husband ignored her and frequented her lovers, in Ferrara Lucrecia surrounded herself with intellectuals and artists and gave free rein to the extraordinary culture and refinement of it.

Her correspondence with Pietro Bembo (1470-1547), one of the most prominent humanists of the time, shows, once again, the extremely high erudition of the Duchess of Ferrara (a title she obtained in 1505, upon the death of the holder, Hercules, her father-in-law), as well as his refined taste and kindness. Not in vain, and as the historian María Pilar Queralt del Hierro quotes in her article The Unjust Bad Fame of Lucrecia Borgia (see bibliography) Pierre Terrail Bayard, a French humanist in Ferrara, says of her that she is “a pearl in this world.” Indeed; It was thanks to the patronage of the new duchess that Ferrara became an even more pronounced epicenter of humanism and culture.

Lucrezia Borgia had finally found peace. The last years of her life (from twenty-one to thirty-nine) were peaceful and serene, completely dedicated to the arts and the education of her children. Her death came too soon, on June 24, 1519, due to terrible puerperal fever. A review of the life of Lucrecia Borgia is necessary and urgent to eliminate all traces of the black legend that still persist and that Romanticism, through her novels, plays and poems (and even an opera) contributed to increasing . Because Lucrecia Borgia was nothing more than an unfortunate woman who had the misfortune of being born into an ambitious family, who did not hesitate to use her as a bargaining chip for their political and economic interests. As she herself signed in her letters: the “unhappy one”.