Life justifies itself, since the ultimate goal of every living being is survival, and consequently, the propagation of its species in all the media that allow its development. To explain this “lust for life” such interesting hypotheses as panspermia are proposed, which argues with reliable data that it is more than likely that we are not alone in the solar system.

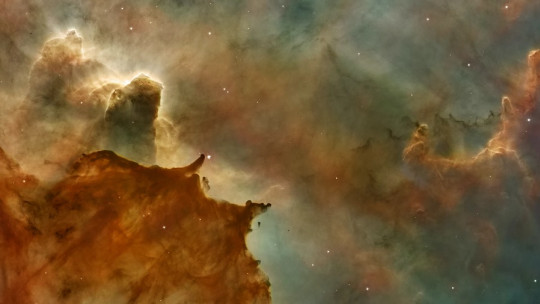

When looking at the stars it is inevitable for us to think about the infinity of the universe, since only our solar system dates back 4.6 billion years and has a diameter of 12,000 million kilometers. These concepts are incomprehensible to the human mind, and therefore, it is easy to suspect that the idea of “life” as our mind conceives it does not serve to describe biological entities external to the earth.

Immerse yourself with us on this astronautic journey in panspermia, or what is the same, the hypothesis that postulates that there is life in the universe transported by meteorites and other bodies

What is panspermia?

As we have hinted at in the previous lines, panspermia is defined as a hypothesis that proposes that life exists throughout the universe and is in motion attached to space dust, meteorites, asteroids, planetoid comets and also space structures for human use that transport microorganisms unintentionally.

Once again, we emphasize that we are faced with a hypothesis, that is, an assumption made from some bases that serves as a pillar to start an investigation or an argument. The information presented here should by no means be taken as an immutable reality or dogma, but it is true that there is increasingly more reliable evidence that supports the hypothesis that we present here.

Furthermore, it must also be made clear that the concept of “extraterrestrial” based on the popular imagination is out of place in the formulation of these ideas. At all times we talk about microorganisms or living beings analogous to them not morphologically complex foreign entities.

Once these initial clarifications have been made, let’s look at the points for and against this exciting application.

Extremophiles and survival in space

An Extremophile, as its name suggests, is a microorganism that can live in extreme conditions In general, these microscopic living beings live in those places where the presence of complex animals or plants is impossible, either due to temperatures, acidity, high amounts of radiation and many other deleterious parameters for “normal” entities. The question is obvious: can Extremophiles live in space?

To answer this question, a research team exposed spores of the bacterial species Bacillus subtilis to space conditions, by transporting them in FOTON satellites (capsules sent into space for research purposes). The spores were exposed to space in dry layers without any protective agent, in layers mixed with clay and red sandstone (among other compounds) or in “artificial meteorites”; that is, structures that combined spores within and on rock formations that tried to imitate natural inorganic bodies in space.

After two weeks of exposure to spatial conditions, the survival of the bacteria was quantified according to the number of colony formers. The results will surprise you:

This only confirms an idea that has already been demonstrated in the terrestrial environment: the ultraviolet radiation produced by sunlight is deleterious for living beings that inhabit the earth when they leave the atmosphere. Still, experiments like this record that Solid mineral materials are capable of acting as “shields” if they are in direct contact with the microorganisms carried in them

The data presented here propose that rocky celestial bodies with a few centimeters in diameter could protect certain life forms from extreme insolation, although micrometer-sized objects may not provide the protection necessary for the preservation of life in space.

Lithopanspermia

Lithopanspermia is the most widespread and established form of possible panspermia , and is based on the transport of microorganisms through solid bodies such as meteorites. On the other hand we have radiopanspermia, which justifies that microbes could be spread through space thanks to the pressure of radiation from stars. Without a doubt, the main criticism of this last theory is that it largely ignores the lethal action of space radiation in the cosmos. How is a bacteria going to survive without any type of protection from space conditions?

The example that we have provided here in the previous section responds to part of the transport process of microorganisms between planetary bodies, but the trip is just as important as the landing. For this reason, some of the hypotheses that must be tested the most today are those based on the viability of microorganisms when leaving the planet and entering a new one.

As far as ejection is concerned, the microorganisms They should withstand extreme acceleration and shock forces, with drastic increases in temperature on the surface on which they travel associated with these processes. These deleterious conditions have been simulated in laboratory environments through the use of rifles and ultracentrifuges with success, although this does not have to fully confirm the viability of certain microorganisms after planetary ejection.

In addition to space transit, another especially delicate moment is atmospheric entry. Fortunately, these conditions are experimentally simulatable, and research has already subjected microorganisms to entry into our planet using sounding rockets and orbital vehicles.

Again, the spores of the Bacillus subtilis species were inoculated into granite rock bodies and subjected to atmospheric hypervelocity transit after being launched in a rocket. The results are again promising, because although the microorganisms located on the front face of the mineral body did not survive (this descending face was subjected to the most extreme temperatures, 145 degrees Celsius), those on the sides of the rock yes they did.

So, as we have seen, from an experimental point of view the presence of life in space mineral bodies seems plausible. Although barely and under certain very specific conditions, it has been shown that certain microorganisms survive during the various necessary stages involved in an interplanetary journey

An increasingly less well-founded criticism

The main detractors of the panspermia hypothesis argue that it is notor responds to the origin of life, but they simply place it on another celestial body Yes, the first microorganisms could have arrived on Earth inside meteorites and been circulating throughout the universe, but where did these bacteria originally come from?

We must also keep in mind that this term was used in its most basic meaning for the first time in the 5th century BC. C., so over the centuries, the detractors of this idea have argued that it is a process that is impossible to explain.

New scientific advances have been combating this preconception for years, since as we have seen, the survival of microorganisms in planetary ejection, during transit and after entry into the atmosphere has already been demonstrated. Of course, a note is necessary: everything collected so far has been under experimental conditions with terrestrial microorganisms

Summary

So let’s be clear: is panspermia possible? From a theoretical point of view, yes. Is panspermia probable? As we have seen in scientific trials, too. Finally: is panspermia proven? We fear not yet.

Although the experimental conditions have shown the viability of this hypothesis, The day has not yet come when a meteorite fallen on Earth gives us extraterrestrial life Until this happens, panspermia (especially lithopanspermia) will remain a hypothesis, which can only be elevated by reliable and indisputable proof. Meanwhile, humans will continue to look up at the stars and wonder if we are alone in the universe.