We cannot talk about the modern conception of personality without talking about Bandura, which is why we invite you to read this PsicologíaOnline article, in which we will delve into the Personality Theories in Psychology: Albert Bandura

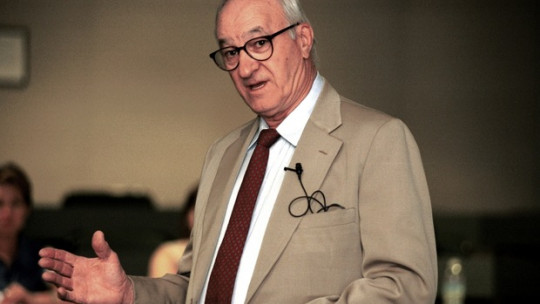

Biography

Albert Bandura was born on December 4, 1925 in the small town of Mundare in Northern Alberta, Canada. He was educated in a small elementary school and college in a single building, with minimal resources, although with a significant success rate. After high school, he worked for a summer filling holes in the Alaska Highway in the Yukon.

He completed his bachelor’s degree in Psychology from the University of British Columbia in 1949. He then transferred to the University of Iowa, where he met Virginia Varns, a nursing school instructor. They married and later had two daughters. Following his graduation, he took up a post-doctoral candidacy at the Wichita Guidance Center in Wichita, Kansas.

In 1953, he began teaching at Stanford University. While there, she collaborated with his first graduate student, Richard Walters, resulting in a first book titled Teenage Aggression in 1959. Sadly, Walters died young in a motorcycle accident.

Bandura was President of the APA in 1973 and received the Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions in 1980. He remains active to this day at Stanford University.

Theory

behaviorism with its emphasis on experimental methods, It focuses on variables that can be observed, measured and manipulated and rejects everything that is subjective, internal and unavailable (pe the mental). In the experimental method, the standard procedure is to manipulate one variable and then measure its effects on another. All of this leads to a theory of personality that says that one’s environment causes our behavior.

Bandura considered that This was a little simple for the phenomenon I was observing (aggression in adolescents) and therefore decided to add a little more to the formula: he suggested that the environment causes the behavior; true, but that behavior causes the environment as well. He defined this concept with the name reciprocal determinism: the world and a person’s behavior cause each other.

Later, he went a step further. He began to consider personality as an interaction between three “things”: the environment, behavior, and the person’s psychological processes. These processes consist of our ability to harbor images in our minds and in language. From the moment he introduces imagination in particular, he stops being a strict behaviorist and begins to approach the cognitivists. In fact, he is usually considered the father of the cognitive movement.

Adding imagination and language to the mix allows Bandura to theorize much more effectively than, say, BF Skinner regarding two things that many people consider “the strong core” of the human species: learning by observation (modeling). ) and self-regulation.

Learning by observation or modeling

Of Bandura’s hundreds of studies, one group stands above the rest, booby doll studies. She made it from a film by one of her students, where a young student was just hitting a silly doll. In case you don’t know, a booby doll is an inflatable egg-shaped creature with a certain weight on its base that makes it wobble when hit. Currently they have Darth Vader painted, but at that time it had the clown “Bobo” as the protagonist.

The young woman hit the doll, shouting “stupid!” She hit him, sat on him, hit him with a hammer and did other things, shouting various aggressive phrases. Bandura showed the film to a group of kindergarten children who, as you can imagine, jumped for joy when they saw it. Afterwards she was left to them to play. In the game room, of course, there were several observers with pens and folders, a new silly doll, and some small hammers.

And you will be able to predict what the observers noted: a large chorus of children shamelessly beating the silly doll. They hit him shouting “stupid!”, they sat on him, they hit him with hammers and so on. In other words, they imitated the young woman in the movie, and quite accurately.

This might seem like an experiment with little input at first, but consider for a moment: these children changed their behavior without initially having reinforcement aimed at exploiting said behavior! And while this may not seem extraordinary to any parent, teacher, or casual observer of children, it didn’t fit very well with standard behavioral learning theories. Bandura called the phenomenon learning by observation or modeling, and his theory is usually known as the social learning theory.

Bandura carried out a large number of variations on the study in question: the model was rewarded or punished in various ways in different ways; children were rewarded for their imitations; The model was changed for another less attractive or less prestigious one and so on. In response to criticism that the clown was made to be “hit,” Bandura even made a movie where a girl hit a real clown. When the children were led to the other playroom, they found what they were looking for…a real clown! They proceeded to kick him, hit him, hit him with a hammer, etc.

All these variants allowed Bandura to establish that there are certain steps involved in the modeling process:

1. Attention. If you’re going to learn something, you need to be paying attention. In the same way, anything that hinders attention will result in a detriment to learning, including observational learning. If, for example, you are sleepy, high, sick, nervous or even “hyper”, you will learn less well. The same thing happens if you are distracted by a competitive stimulus.

Some of the things that influence attention have to do with the properties of the model. If the model is colorful and dramatic, for example, we pay more attention. If the model is attractive or prestigious or appears to be particularly competent, we will pay more attention. And if the model is more like us, we will pay more attention. These types of variables directed Bandura towards the examination of television and its effects on children.

2. Retention. Second, we must be able to retain (remember) what we have paid attention to. This is where imagination and language come into play: we store what we have seen the model do in the form of mental images or verbal descriptions. Once “archived”, we can resurface the image or description so that we can reproduce it with our own behavior.

3. Playback. At this point, we’re just there daydreaming. We must translate the images or descriptions to the current behavior. Therefore, the first thing we must be able to do is reproduce the behavior. I can spend a whole day watching an Olympic skater doing his job and not be able to reproduce his jumps, since I don’t know how to skate at all! On the other hand, if I could skate, my performance would actually improve if I watched better skaters. that I.

Another important issue regarding reproduction is that our ability to imitate improves with practice of the behaviors involved in the task. And another thing: our skills improve even just by imagining ourselves doing the behavior! Many athletes, for example, imagine the act they are going to do before carrying it out.

4. Motivation. Even with all this, we still won’t do anything unless we are motivated to imitate; that is, unless we have good reasons to do so. Bandura mentions a number of reasons:

- Past reinforcementlike traditional or classical behaviorism.

- Promised reinforcements(incentives) that we can imagine.

- Vicarious reinforcementthe possibility of perceiving and recovering the model as a reinforcer.

Note that these reasons have traditionally been considered those things that “cause” learning. Bandura tells us that these are not so much causative as samples of what we have learned. That is, he considers them more as motives.

Of course, negative motivations also exist, giving us reasons not to imitate:

- past punishment.

- Promised punishment (threats)

- Vicarious punishment.

Like most classical behaviorists, Bandura says that punishment in its various forms does not work as well as reinforcement and, in fact, has a tendency to backfire.

Self-regulation

Self-regulation (controlling our own behavior) is the other cornerstone of human personality. In this case, Bandura suggests three steps:

1. Self-observation. We see ourselves, our behavior and take clues from it.

2. Judgment. We compare what we see with a standard. For example, we can compare our actions with other traditionally established ones, such as “rules of etiquette.” Or we can create some new ones, like “I will read a book a week.” Or we can compete with others, or with ourselves.

3. Auto-response. If we have done well in the comparison with our standard, we give reward responses to ourselves. If we don’t come out well, we will give ourselves punitive self-responses. These self-responses can range from the most obvious extreme (saying something bad to ourselves or working late), to the more covert one (feelings of pride or shame).

A very important concept in psychology that could be well understood with self-regulation is self-concept (better known as self-esteem). If over the years, we see that we have acted more or less according to our standards and have had a life full of personal rewards and praise, we will have a pleasant self-concept (high self-esteem). If, on the contrary, we have always seen ourselves as incapable of reaching our standards and punishing ourselves for it, we will have a poor self-concept (low self-esteem).

Note that behaviorists generally consider reinforcement as effective and punishment as fraught with problems. The same goes for self-punishment. Bandura sees three possible results of excessive self-punishment:

Compensation. For example, a superiority complex and delusions of grandeur.Inactivity. Apathy, boredom, depression.Exhaust. Drugs and alcohol, television fantasies or even the most radical escape, suicide.

The above has some resemblance to the unhealthy personalities that Adler and Horney talked about; the aggressive type, the submissive type and the avoidant type respectively.

Bandura’s recommendations for people suffering from poor self-concepts arise directly from the three steps of self-regulation:

Concerning self-observation. know yourself!. Make sure you have an accurate picture of your behavior.

Concerning standards. Make sure your standards are not set too high. Do not we embark in a road to failure. However, standards that are too low are meaningless.

Concerning self-response. Use personal rewards, not self-punishments. Celebrate your victories, don’t deal with your failures.

Therapy

Self-control therapy

The ideas on which self-regulation is based have been incorporated into a therapeutic technique called self-control therapy. It has been quite successful with relatively simple habit problems such as smoking, overeating, and study habits.

1. Tables (records) of behavior. Self-observation requires us to note types of behavior, both before we start and after. This act includes things as simple as counting how many cigarettes we smoke in a day to behavior diaries more complex. By using journals, we take note of details; the when and where of the habit. This will allow us to have a more concrete vision of those situations associated with our habit: do I smoke more after meals, with coffee, with certain friends, in certain places…?

2. Environmental planning. Having a log and journals will make it easier for us to take the next step: alter our environment. For example, we can remove or avoid those situations that lead us to bad behavior: removing the ashtrays, drinking tea instead of coffee, divorcing our smoking partner… We can look for the time and place that are best to acquire better alternative behaviors: where And when do we realize that we study better? And so on.

3. Self-contracts. Finally, we commit to compensating ourselves when we stick to our plan and punishing ourselves if we don’t. These contracts must be written in front of witnesses (by our therapist, for example) and the details must be very well specified: “I will go to dinner on Saturday night if I smoke fewer cigarettes this week than last. If I don’t, I will stay. working at home”.

We might also invite other people to monitor our rewards and punishments if we know we won’t be too strict on ourselves. But be careful: this can lead to the end of our relationships as we try to brainwash them in an attempt to get them to do things the way we would like!

Modeling Therapy

However, the therapy for which Bandura is best known is modeling. This theory suggests that if you choose someone with a psychological disorder and have them observe someone else who is trying to deal with similar problems in a more productive way, the first will learn by imitation of the second.

Bandura’s original research on the subject involves work with herpephobes (people with neurotic fears of snakes). The client is led to observe through a glass window that overlooks a laboratory. In this space, there is nothing but a chair, a table, a box on top of the table with a lock and a snake clearly visible inside. Then, the person in question sees another person (an actor) approaching, slowly and fearfully heading towards the box. At first he acts very scary; He shakes himself several times, tells himself to relax and breathe easily, and takes one step at a time toward the snake. He may stop along the way a couple of times; retreat in panic, and start again. In the end, he reaches the point of opening the box, picks up the snake, sits on the chair and grabs it by the neck; all this while he relaxes and gives himself calm instructions.

After the client has seen all this (no doubt with his mouth open throughout the entire observation), he is invited to try it himself. Imagine, he knows that the other person is an actor (no deception here; just modeling!) And yet, many people, chronic phobics, embark on the entire routine from the first try, even when they have seen the scene alone once. This, of course, is a powerful therapy.

One drawback of the therapy was that it is not so easy to get the rooms, the snakes, the actors, etc., all together. So Bandura and her students tried different versions of the therapy using recordings of actors and even appealed to the imagination of the scene under the tutelage of therapists. These methods worked almost as well as the original.

Discussion

Albert Bandura had an enormous impact on personality theories and therapy His bold, behaviorist-like style seemed quite logical to most people. His action-oriented, problem-solving approach was welcomed by those who liked action more than philosophizing about the id, archetypes, actualization, freedom, and all the other mentalistic constructs that personologists tend to study.

Within academic psychologists, research is crucial and the Behaviorism has been his preferred approach Since the late 1960s, behaviorism has given way to the “cognitive revolution,” of which Bandura is considered a part. Cognitive psychology retains the flavor of the experimental orientation of behaviorism, without artificially retaining the researcher from external behaviors, when precisely the mental life of clients and subjects is so obviously important.

This is a powerful movement, and its contributors include some of the most prominent people in psychology today: Julian Rotter, Walter Mischel, Michael Mahoney, and David Meichenbaum are a few who come to mind. There are also others dedicated to therapy such as Beck (cognitive therapy) and Ellis (rational-emotive therapy). Followers and later George Kelly are also in this field. And the many other people who are dealing with the study of personality from the point of view of traits, such as Buss and Plomin (temperament theory) and McCrae and Costa (five-factor theory) are essentially cognitive behaviorists like Bandura.

My feeling is that the field of competitors in personality theory will eventually devolve into cognitiveists on the one hand and existentialists on the other. Let’s stay alert.

Bandura’s theory can be found in Social Foundations of Thought and Action (1986) If we think it is too dense for us, we can go to his previous work Social Learning Theory(1977), or even Social Learning and Personality Development(1963), where he writes with Walters. If we are interested in aggression, let’s see Aggression: A Social Learning Analysis (1973).

This article is merely informative, at PsychologyFor we do not have the power to make a diagnosis or recommend a treatment. We invite you to go to a psychologist to treat your particular case.

If you want to read more articles similar to Personality Theories in Psychology: Albert Bandura we recommend that you enter our Personality category.