All living beings (except humans) exist and persist on Earth with a single specific objective: to leave as many offspring as possible.

The conception of the individual in nature does not matter, since what is relevant is biological fitness, or what is the same, the amount of genes that a specimen can transmit throughout its life to the next generation, either in the form of offspring or blood relatives.

Many living beings have developed atypical reproduction techniques based on this premise. For example, asexual reproduction partially responds to the energy investment dilemma: if you reproduce by partition, you do not spend resources searching for a mate. This mechanism may seem perfect, but the reality is that sexuality is the key to evolution: if all specimens are the same as their parents, no adaptations occur.

The key to reproduction in the world of living beings is to find the most effective middle point, the balance between leaving a lot of offspring and making them viable, that is, surviving in an environment that is as demanding as it is dynamic. Today we tell you everything about polyembryony a biological phenomenon that will never cease to surprise human beings.

The bases of reproduction in the animal kingdom

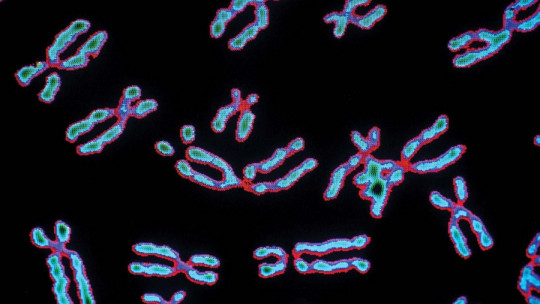

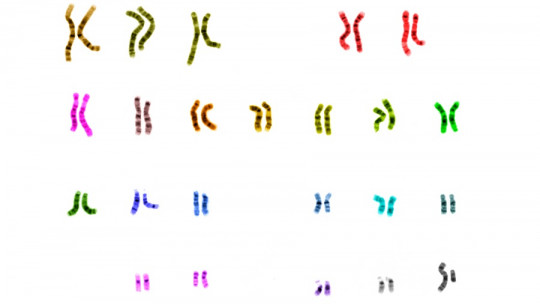

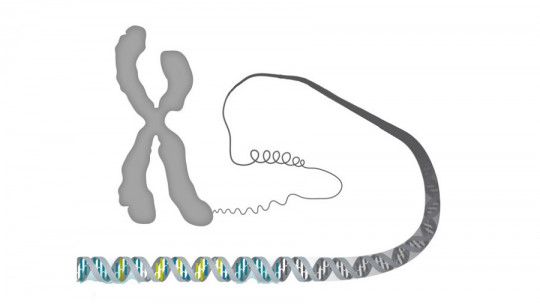

Reproduction in humans (and most vertebrates) is quite straightforward. Our species is diploid (2n), which means that we have two copies of each chromosome in each of our body cells, one inherited from the mother and one from the father. The karyotype, therefore, is as follows: 23 parental chromosomes + 23 maternal chromosomes, 46 total. The last pair of chromosomes is the one that determines sex, with the possible variants being XX (female) and XY (male).

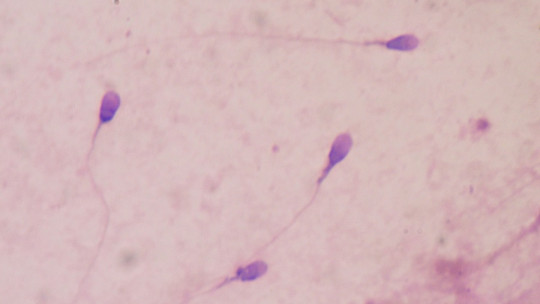

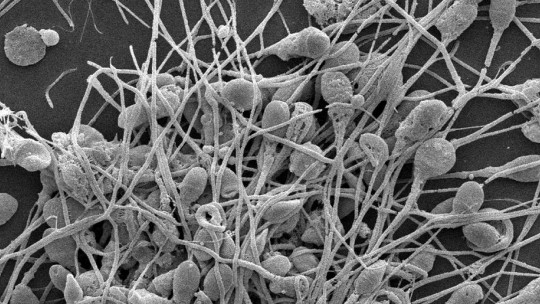

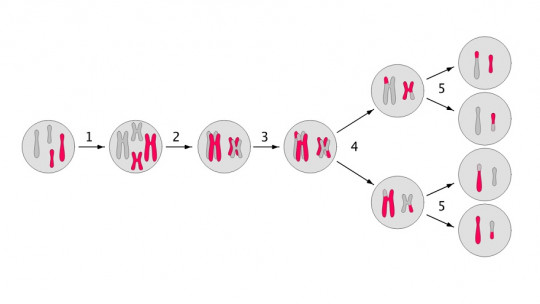

When gametes are formed, the genetic information is “split in half” , otherwise, each generation would have more and more chromosomes than the previous one (2n, 4n, 8n, 16n, etc.). For this reason, the precursor cells of the eggs and sperm must divide by meiosis, in order to remain with only 23 chromosomes. Phenomena such as crossing over or chromosomal permutation occur here, which means that each new descendant is not just the sum of its parts.

Once the gametes have been formed and both individuals of the opposite sex have reproduced, fertilization occurs. In this event, a zygote is formed that recovers diploidy (n+n,2n) and is a product of the paternal and maternal genome, in equal parts. An embryo is derived from the zygote, which grows in the maternal placenta, becoming called a fetus from the twelfth week.

We have described the general reproductive mechanism in mammals, but There are clear exceptions to this rule Some living beings (such as certain starfish) create copies of themselves by breaking off a part of their body (autotomy), while there are living beings that are directly haploid. Without going any further, the males of ant colonies have half the genetic information of the queens and workers, since they are the product of a cell that has not been fertilized, or in other words, they are haploid.

What is polyembryony?

Polyembryony is a reproductive mechanism in which two or more embryos develop from a single fertilized gamete In other words, an egg and a sperm give rise to more than one offspring, unlike what would be expected in the reproductive model mentioned above. The zygote is produced by sexual reproduction, but then it divides asexually within the maternal environment.

Sounds ideal, right? A female of a polyembryonic species can have 2.3 or more children in the same reproductive event, and therefore, with a lower energy investment. As positive as it may sound, in nature there is a maxim: if a character has not been established among related species, there must be something wrong with it, without exception. If polyembryony were extremely successful, in the end living beings with this strategy would expand throughout the world and displace those that are not. As you can see, this has not been the case.

One of the keys to polyembryony is that Children are different from parents, but equal to each other Since they all come from the same zygote, they have the same genetic information (barring mutations) and the same sex. In this reproductive strategy, quantity prevails over quality, since all descendants being equal has a series of repercussions for the species, both good and bad.

Polyembryony is very common in plants, but we find it more interesting to focus on the animal kingdom. For example, all armadillos of the genus Dasypus They are polyembryonic. Only one fertilized egg can implant in the maternal environment, but due to this capacity for division, 4 offspring of the same sex and genetically identical result. Studies have shown that this does not correlate with greater cooperativity or altruism among siblings, so polyembryony is not explained by kin selection (or kin selection).

The only possible explanation for this phenomenon in this species is morphological constrictions. It is stipulated that polyembryonic species are so only out of necessity, not because it is a more viable strategy. A dog can have a litter of 5 different puppies in a single birth, but the armadillo’s uterine implantation site is too small to accommodate 4 zygotes from different fertilizations. Thus, once implanted, a single one can divide asexually and give rise to several offspring It is not the ideal scenario, but as they say in animal anatomy, “nature does what it can with what it has.”

Polyembryony in humans

We cannot end this space without mentioning that polyembryony exists in humans Twins are proof of this, since they both come from the same fertilization event and are genetically identical, again, excluding spontaneous mutations that may occur during division or development. It is important not to confuse this biological event with twins, since they are genetically different. Twins arise when two zygotes (products of different fertilizations) implant at the same time, so they are not equal.

The phase in which the zygote splits is extremely important for the viability of the twins We exemplify it in the following list:

Besides all this, twins have a growth restriction at birth, generally 10 to 15% With all these figures, you can understand why polyembryony is not a viable strategy in mammals or, at least, in humans.

Summary

As you may have seen, polyembryony is a reproductive strategy in the form of a double-edged sword. Having more children in a single reproductive event is easier than not doing so, but the offspring are genetically equal to each other and, in species that are not typically polyembryonic, a series of associated complications also appear, ranging from growth retardation to death. of the fetuses.

For all these reasons, polyembryony is a strategy that is very limited in the animal kingdom. Whenever possible, animals resort to having multiple litters, but as a result of different fertilization events. Thus, the genetic variability of the offspring remains intact.