You’re walking through a crowded street when suddenly a whiff of perfume stops you in your tracks. Instantly, you’re transported back twenty years to your grandmother’s living room—you can see the afternoon light filtering through lace curtains, hear the clock ticking on the mantle, feel the texture of the velvet sofa, and most powerfully, experience the exact emotional quality of those childhood Sunday visits. The memory arrives complete, vivid, and unbidden, triggered by nothing more than a fleeting scent. Or perhaps you’re biting into a particular food when a long-forgotten memory from decades ago floods back with startling clarity and emotional intensity. These experiences aren’t random coincidences or signs of an overactive imagination—they’re examples of the Proust Effect, also known as the Madeleine Effect, a well-documented psychological phenomenon where sensory stimuli, particularly smell and taste, trigger powerful involuntary autobiographical memories accompanied by intense emotional experiences.

The phenomenon takes its name from French novelist Marcel Proust, whose monumental seven-volume work À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time) contains one of literature’s most famous descriptions of sensory-triggered memory. In the opening volume, Proust’s narrator tastes a small piece of madeleine cake dipped in lime-blossom tea—a simple sensory experience that suddenly unleashes an overwhelming cascade of childhood memories. The taste and smell don’t just remind him intellectually of the past; they transport him there completely, bringing back his aunt Léonie’s bedroom, the old grey house in the village of Combray, the streets where he ran errands, the garden, even the water-lilies on the river Vivonne. What makes this passage remarkable isn’t just its literary beauty but its psychological accuracy. Proust, writing in the early 20th century without access to modern neuroscience, captured with extraordinary precision how olfactory and gustatory cues can trigger involuntary memories that are more vivid, more emotionally charged, and more complete than memories we consciously try to recall. Decades later, scientific research would confirm what Proust described: smell-triggered memories are indeed processed differently in the brain, are more emotionally evocative, and feel more like re-experiencing the past than simply remembering it.

The Proust Effect has become more than a literary reference—it’s now recognized in psychology and neuroscience as a genuine phenomenon worthy of serious study. Research has shown that scent-evoked memories are significantly more emotional and evocative than memories triggered by other sensory cues, including visual stimuli which are typically our dominant sense. This peculiarity stems from the unique neurological pathway that connects smell directly to the brain’s emotional and memory centers—the amygdala and hippocampus—bypassing the thalamus that processes other sensory information. This direct connection means smell has privileged access to our emotional memory systems in ways that sight, sound, or touch do not. Studies have found that scent-evoked nostalgia provides numerous psychological benefits including enhanced self-esteem, feelings of social connectedness, deeper meaning in life, and improved mood. The phenomenon calls into question assumptions about memory itself: if our most vivid and emotionally powerful memories are triggered by sensory experiences rather than conscious recall, and if these memories are colored by the emotions we felt at the time rather than objective facts, what does this tell us about the nature of memory, identity, and our relationship with our past? Whether you’ve experienced your own “madeleine moment” or are simply curious about the mysterious workings of memory and emotion, understanding the Proust Effect offers fascinating insights into how your brain stores the past, why certain memories feel more “real” than others, and how the simple act of smelling something can collapse decades and transport you instantly to another time and place.

What Is the Proust Effect?

The Proust Effect, also called the Proust phenomenon or Proustian memory, refers to the sudden, involuntary evocation of autobiographical memory triggered by sensory experiences—particularly smell and taste—that includes not just factual recall but a rich constellation of sensory details and emotional states associated with the original memory. This isn’t the ordinary remembering we do when someone asks “what did you do last weekend?” That’s voluntary memory, where you consciously search your mind for information and reconstruct events. The Proust Effect involves involuntary memory, where the past arrives unbidden, often with startling vividness and completeness, triggered by an external sensory cue rather than conscious effort.

Proust himself distinguished between these two types of memory in his novel. Voluntary memory, he suggested, delivers only superficial information—facts, dates, sequences of events—but misses the “essence of the past.” It’s memory mediated by intellect, reconstructed consciously, and often feels distant or abstract. Involuntary memory, by contrast, captures something deeper and more authentic—the subjective feeling-tone of lived experience, the emotional quality that made a particular moment in your life feel the way it did. When Proust’s narrator tastes the madeleine dipped in tea, he doesn’t just remember intellectually that he used to eat such cakes at his aunt’s house. Instead, he experiences a rush of sensation and emotion that feels like actually being there again—the visual details, the sounds, the atmosphere, and crucially, the emotional state of his childhood self.

What makes the Proust Effect particularly distinctive is its specificity and completeness. Unlike vague reminders or simple associations, Proustian memories typically arrive as rich, multi-sensory experiences. A particular smell doesn’t just make you think “oh, that reminds me of my father”—it might transport you to a specific afternoon in his workshop when you were seven years old, bringing back the exact quality of light through the dusty windows, the feel of wood shavings under your feet, the sound of his radio playing in the background, and the precise emotional texture of that moment—perhaps a feeling of safety, curiosity, or quiet contentment. The memory feels less like remembering and more like re-experiencing or time-traveling.

The phenomenon is also characterized by its involuntary and often surprising nature. You’re not searching for these memories; they ambush you. Often, you’ve completely forgotten the memory that surfaces—it may have been inaccessible through conscious recall for years or decades. The sensory trigger acts like a key that unlocks something that was stored but buried. This is why Proustian moments often feel revelatory or even mystical—you’re suddenly confronted with a part of your past that you didn’t know you still carried, experiencing emotions and details you thought were lost forever.

Key Characteristics of the Proust Effect

Several distinctive features characterize genuine Proustian memories and distinguish them from ordinary memory recall. The most striking characteristic is the emotional intensity and vividness that accompanies these memories. Research has consistently demonstrated that scent-evoked autobiographical memories are rated as significantly more emotional and evocative than memories triggered by verbal cues or even visual stimuli. When you remember something because someone mentions it in conversation, you access information but often without strong emotional coloring. When a smell triggers a memory, the emotional component is not just present but often overwhelming—you don’t just remember that your grandmother loved you; you feel, in that moment, exactly how it felt to be loved by her.

Another defining characteristic is the multi-sensory completeness of these memories. Proust described how the taste of the madeleine brought back not just one isolated memory but an entire world: the house, the town, the garden, the people, the streets—a complete experiential package. This aligns with how researchers understand memory encoding: experiences aren’t stored as isolated facts but as interconnected networks of sensory information, emotions, and context. When a powerful sensory cue activates one part of this network—particularly through smell, which has unique access to emotional memory systems—it can trigger the entire complex, bringing back layers of detail that wouldn’t emerge through conscious recall efforts.

The autobiographical and personal nature of Proustian memories is also characteristic. These aren’t semantic memories (general knowledge like facts or concepts) but episodic memories—specific events from your personal past. Moreover, they’re typically memories from relatively distant past, often childhood or young adulthood, though they can come from any period of life. There’s something about long-dormant memories that makes them particularly susceptible to this kind of sudden, complete recall when triggered by the right sensory cue. Memories you access regularly through conscious recall tend not to produce the same shocking vividness—they’ve been retrieved and reconstructed so many times that they’ve become somewhat abstracted. The memories most vulnerable to Proustian recall are those that haven’t been consciously accessed in years but were encoded during emotionally significant periods of your life.

The experience also characteristically includes a sense of temporal collapse—the boundary between past and present momentarily dissolves. You’re simultaneously aware that you’re standing in a grocery store in 2025 and that you’re seven years old in your grandmother’s kitchen in 1995. This dual consciousness, where past and present coexist, gives Proustian moments their somewhat surreal quality. Unlike clearly delineated memories where you’re conscious of remembering from your current perspective, the Proust Effect creates something closer to re-experiencing—the past feels present in a way that’s difficult to articulate but immediately recognizable to anyone who’s experienced it.

The Neuroscience: Why Smell Triggers Memory Differently

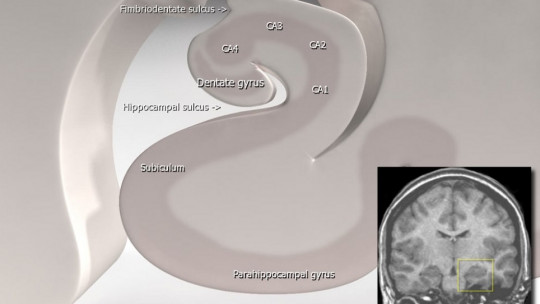

The Proust Effect isn’t just a poetic metaphor—it has a clear neurological basis rooted in how smell is processed in the brain. Unlike all other senses, olfactory information takes a unique pathway that gives it privileged access to emotional and memory centers. When you see, hear, or touch something, the sensory information travels first to the thalamus, a relay station that processes and distributes sensory input to appropriate cortical areas. This processing involves multiple steps and conscious awareness before reaching areas associated with memory and emotion.

Smell works differently. Olfactory nerves connect directly to the olfactory bulb, which has immediate connections to two crucial brain structures: the amygdala (involved in processing emotions and emotional memory) and the hippocampus (critical for forming and retrieving autobiographical memories). This direct pathway means smell information reaches emotional and memory centers with minimal processing, creating a more immediate and visceral connection between scent and memory than exists for other senses. The anatomical closeness between olfactory processing areas and emotion/memory centers essentially hardwires smell into your emotional memory system.

The amygdala’s involvement explains why scent-triggered memories are so emotionally charged. The amygdala assigns emotional significance to experiences and plays a crucial role in emotional memory consolidation—memories formed during emotional arousal are more strongly encoded and more easily retrieved. When you smell something associated with a past experience, it can directly activate the amygdala, which then retrieves not just the factual memory but the emotional state that accompanied the original experience. This is why you don’t just remember your childhood home when you smell a particular scent—you feel the way you felt in your childhood home, experiencing the emotional quality of being seven years old again.

Research has also revealed that smell is particularly effective at encoding context—the surrounding circumstances, atmosphere, and feeling-tone of an experience rather than just specific facts. Vision is excellent for encoding specific details and objects; it’s our dominant sense for gathering information about the world. But vision is also highly cognitive and analytical. Smell, by contrast, is more holistic and contextual. It captures the “atmosphere” of a place or time. When that smell returns, it brings the entire contextual package with it—the general ambiance, emotional tone, and subjective experience of being in that place and time, rather than just isolated facts about it.

Causes and Triggers of the Proust Effect

The Proust Effect emerges from the intersection of several factors involving memory formation, emotional significance, and the unique properties of olfactory processing. Emotional arousal during the original experience is perhaps the most critical factor. Memories formed during emotionally significant moments—whether positive or negative—are more strongly encoded in the brain. Studies have consistently shown that emotional events are remembered more vividly and with more detail than neutral events. When smell is present during these emotionally significant experiences, it becomes encoded as part of the memory trace, creating a powerful retrieval cue that can later unlock the entire memory complex.

The timing of the original memory formation matters significantly. Childhood and adolescence appear to be particularly fertile periods for forming memories that later become susceptible to Proustian recall. This relates to the “reminiscence bump”—the psychological phenomenon where adults tend to have a disproportionate number of autobiographical memories from ages 10-30, particularly from adolescence and early adulthood. These formative years involve intense emotional experiences, identity formation, and first-time experiences that create especially strong memory encoding. Additionally, the child and adolescent brain may encode sensory information differently than the adult brain, creating memory traces that are particularly responsive to sensory triggers later in life.

The rarity or distinctiveness of the smell influences whether it becomes an effective trigger. Common smells that you encounter constantly don’t tend to produce Proustian moments because they’re not distinctive enough to serve as specific memory markers. A smell you experience daily becomes part of your current sensory background rather than a key to the past. However, a smell that was common in childhood but rarely encountered in adulthood—like a specific type of soap, a particular cooking smell, or a seasonal scent—maintains its connection to that earlier time period. When you finally encounter it again after years or decades, it hasn’t been overwritten by new associations and can trigger those older memories intact.

The interval between original experience and later encounter also matters. Proustian moments often involve significant time gaps—years or decades between the original memory formation and the sensory trigger that recalls it. During this interval, the memory typically hasn’t been consciously accessed much or at all. This lack of conscious rehearsal means the memory hasn’t been repeatedly reconstructed and potentially altered, preserving something closer to the original encoding. When the sensory trigger appears, it can access this relatively pristine memory trace, producing the sense of sudden, complete, and vivid recall that characterizes the Proust Effect.

Finally, the phenomenon requires a confluence of factors that aren’t always present, which explains why we don’t experience Proustian moments constantly despite encountering smells throughout our days. The specific smell must have been present during emotionally significant experiences that were strongly encoded, must be distinctive enough to serve as a specific memory cue, must not have been encountered so frequently that it’s lost its specificity, and must be encountered when you’re in a receptive state—not necessarily consciously searching for memories but open to the experience. When all these factors align, the conditions exist for that remarkable experience of the past suddenly flooding back with complete, vivid, emotional intensity.

Benefits and Functions of Proustian Memory

Beyond their subjective fascination, Proustian memories appear to serve important psychological functions and provide measurable benefits. Research has identified numerous positive effects associated with scent-evoked nostalgia, which is closely related to the Proust Effect. Studies show that when people experience nostalgic memories triggered by scents, they report enhanced self-esteem, increased feelings of social connectedness, greater optimism, stronger sense of meaning in life, and improved mood. These aren’t trivial effects—they represent significant psychological resources that contribute to wellbeing and resilience.

One crucial function appears to be maintaining self-continuity—the sense that you’re the same person across time despite changes in circumstances, appearance, beliefs, and life situations. Proustian moments reconnect you with your past self in an immediate, visceral way that abstract remembering cannot. When you smell something that transports you to childhood, you experience yourself as that child again while simultaneously being your adult self. This creates a felt sense of continuous identity stretching across decades. In a rapidly changing world where we constantly reinvent ourselves, these moments of connection with past selves provide psychological anchoring and coherence.

The emotional regulation benefits of nostalgia and nostalgic memories have also been documented. Feelings of nostalgia appear to buffer against loneliness, anxiety, and existential concerns. Scent-evoked memories that bring back times when you felt loved, safe, or happy can provide emotional comfort in difficult present circumstances. This isn’t about living in the past or avoiding present reality—it’s about accessing emotional resources from your personal history that help you cope with current challenges. The vivid re-experiencing that characterizes the Proust Effect may be particularly effective for this purpose precisely because it’s not abstract remembering but something closer to actually feeling those positive emotional states again.

Some researchers and therapists have explored therapeutic applications of scent-evoked memory. For people dealing with trauma, depression, or disconnection from positive experiences, carefully selected scents associated with happier times might help access emotional resources that feel distant or inaccessible. Conversely, understanding how scent can trigger traumatic memories helps explain certain PTSD responses and suggests the importance of addressing olfactory triggers in trauma treatment. Essential oils and aromatherapy practices, while sometimes dismissed as pseudoscience, may have legitimate psychological effects precisely through these scent-memory-emotion connections, though more rigorous research is needed to establish specific protocols and effectiveness.

FAQs About the Proust Effect

Why is smell more powerful than sight for triggering emotional memories?

Despite sight being our dominant sense for navigating the world and gathering information, smell has unique neurological advantages for accessing emotional memory. The key lies in brain anatomy and the evolutionary history of these sensory systems. Olfactory nerves connect directly to the olfactory bulb, which has immediate connections to the amygdala (emotional processing) and hippocampus (memory formation) without passing through the thalamus that processes other sensory information. This direct pathway gives smell privileged, immediate access to emotional and memory centers. Sight, by contrast, travels first to the thalamus and then to visual processing areas in the cortex before reaching memory and emotional centers. This multi-step pathway involves more processing, more conscious awareness, and more cognitive filtering. Sight is the most cognitive of all senses, as researchers note—it’s analytical and detail-oriented, excellent for gathering specific information but less connected to holistic emotional experiences. Smell is more primitive, evolutionarily older, and more directly wired into limbic structures involved in emotion and memory. Additionally, smell encodes context and atmosphere rather than specific details—it captures the feeling of a place or time rather than precise visual information. When you see a photograph from childhood, you’re processing visual information through your cognitive, analytical systems. When you smell something from childhood, it bypasses analysis and directly activates emotional memory systems, producing that characteristic sensation of being transported back in time. The evolutionary explanation is that smell was crucial for survival in early mammals—detecting food, predators, mates—and needed direct connections to emotional and memory systems for immediate threat assessment and response. These ancient pathways persist in humans, giving smell its peculiar power over emotion and memory despite sight’s dominance in our conscious experience.

Can the Proust Effect work with senses other than smell and taste?

Yes, though the effect is strongest and most characteristic with olfactory and gustatory stimuli. Proust himself emphasized smell and taste because they have those unique direct connections to emotional memory systems. However, other sensory triggers can produce similar experiences of sudden, vivid, emotionally charged memory recall. Music is perhaps the most powerful non-olfactory trigger—hearing a particular song can instantly transport you back to a specific time and place with remarkable vividness and emotional intensity. This works because music is processed in multiple brain areas including those involved in emotion and memory, and because music is often present during emotionally significant experiences. The phenomenon of certain songs becoming “your song” or being forever associated with particular relationships or life periods reflects this powerful music-memory connection. Touch and texture can also trigger Proustian-style memories—feeling a particular fabric, temperature, or texture might suddenly evoke childhood experiences. Even visual triggers occasionally produce this effect, though as researchers note, sight tends to be more cognitive and less emotionally immediate than smell. A visual scene might powerfully remind you of something, but it typically doesn’t produce the same overwhelming, involuntary, visceral rush of memory and emotion that characterizes true Proustian moments. What distinguishes genuine Proust Effect experiences is the involuntary, sudden, complete, and emotionally overwhelming nature of the recall—not just being reminded but being transported. While various sensory triggers can approach this, smell and taste remain the most reliable producers of this specific type of memory experience due to their unique neurological pathways. Some researchers argue that only olfactory/gustatory triggers should properly be called “Proust Effect,” while others use the term more broadly for any involuntary sensory-triggered autobiographical memory. The core principle remains the same: sensory cues encoded during emotional experiences can later serve as powerful retrieval triggers that access not just factual memory but the feeling of the original experience.

Are Proustian memories more accurate than regular memories?

This is a fascinating and complex question that touches on fundamental issues about memory reliability. Proustian memories feel more accurate and authentic—they have a quality of vividness and completeness that makes them seem like direct access to the past rather than reconstruction. However, feeling authentic doesn’t necessarily mean being factually accurate. Memory researchers have established that all autobiographical memories involve reconstruction rather than playback—your brain doesn’t store experiences like a video recording but rather encodes key elements and then rebuilds memories when retrieving them, potentially incorporating information from other times, social influences, and current beliefs. Proustian memories undergo the same reconstructive processes as other memories and are equally susceptible to distortion, confabulation, and incorporation of information from other sources. What makes them distinctive isn’t necessarily greater factual accuracy but greater emotional authenticity—they more faithfully capture the feeling-tone and subjective experience of the original moment. You might remember incorrect details while accurately remembering how it felt to be there. Additionally, the strong emotional coloring of Proustian memories, while part of their power, may also bias them. Research shows that emotional arousal enhances memory for central details but can actually impair memory for peripheral details, and that emotional memories are more confidently held even when inaccurate. The confidence and vividness that characterize Proustian recall can create a false sense of accuracy—you feel certain about details that might actually be wrong or embellished. Proust himself raised this philosophical issue in his novel, questioning the epistemological status of recovered memories. As philosophers of memory note, we cannot fully know whether scent-evoked memories represent accurate retrieval of the past or a particularly vivid form of reconstruction. The memories feel like re-experiencing, but this subjective feeling doesn’t guarantee objective accuracy. What we can say is that Proustian memories likely preserve something authentic about the emotional and experiential quality of the original moment, even if specific factual details may be reconstructed or altered—they capture the essence of how it felt to be you at that earlier time, which is a different kind of truth than factual accuracy.

Can you deliberately create situations where you’ll have future Proustian memories?

While you cannot fully control which memories will later be susceptible to Proustian recall, you can create conditions that make such experiences more likely in the future. The key is intentionally pairing distinctive scents with emotionally significant experiences while being mindfully present during those experiences. If you want to be able to recall a particular period of your life—say, a special vacation, your child’s early years, or a particularly happy phase—you might deliberately use a specific perfume, burning a particular scent, or surrounding yourself with a distinctive smell that’s not part of your regular daily environment. The distinctiveness matters—using a common everyday smell won’t work because it lacks specificity. The emotional significance matters too—the memory needs to be encoded during experiences that engage your emotions, whether joy, love, excitement, or even poignant sadness. Mechanical, routine experiences, even if a distinctive scent is present, are less likely to create strong memory traces. Mindful presence during the experience enhances memory encoding—being fully engaged and aware rather than distracted or on autopilot creates richer, more complete memory traces that are more likely to be susceptible to later sensory triggering. Some people deliberately engage in what might be called “future nostalgia”—consciously noticing and attending to moments they suspect they’ll want to remember, sometimes explicitly thinking “I want to remember this.” This mindful encoding, combined with distinctive sensory markers, may increase the likelihood of later Proustian recall. That said, there’s something about the authenticity and spontaneity of naturally occurring Proustian moments that might be diminished by too much deliberate engineering. The most powerful such experiences often involve memory-scent pairings that occurred naturally, without conscious intent to create future triggers. Additionally, you cannot control when or whether you’ll later encounter the scent you’ve deliberately paired with an experience—if you never smell that particular perfume again, it cannot serve as a memory trigger. The most powerful Proustian moments often involve accidental re-encounters with scents from long ago, and that element of surprise and unexpectedness contributes to their emotional impact. Still, for important life periods you want to preserve in accessible memory, creating distinctive scent associations might be worth attempting, even knowing the process cannot be fully controlled or guaranteed.

Do people with anosmia (inability to smell) experience the Proust Effect differently?

People with anosmia—whether from birth or acquired through injury, illness, or aging—do miss out on the specific form of involuntary memory retrieval that makes olfactory Proustian moments so distinctive. Since they cannot smell, they cannot experience smell-triggered memory recall, which represents a genuine loss given the unique power of olfactory cues for accessing emotional autobiographical memory. Research with people who have lost their sense of smell shows they report feeling disconnected from certain memories and that their memory recall tends to be less emotionally vivid than people with intact olfaction. However, people with anosmia can still experience involuntary memory phenomena triggered by other senses—music, touch, taste (though taste is significantly impaired without smell, they can still detect basic taste qualities), or even particular visual scenes or lighting conditions might produce sudden, vivid memory recall. The mechanism of involuntary memory itself—where external cues trigger unbidden autobiographical recall—doesn’t depend exclusively on smell; smell is simply the most powerful and reliable trigger for this phenomenon due to its unique neurological pathways. People with congenital anosmia (born without sense of smell) have never formed scent-memory associations, so they wouldn’t miss what they never experienced. Their brains may compensate by forming stronger memory associations with other sensory modalities—they might have particularly powerful music-memory or touch-memory connections that serve similar functions. People with acquired anosmia report the loss differently—they remember when smells could trigger memories and experience the loss of this capacity as significant, sometimes describing it as feeling disconnected from their past or finding certain memories harder to access. This highlights how integral smell is to emotional memory and nostalgia for those who have experienced it. Some research suggests that people with anosmia develop richer verbal-memory associations or stronger visual-memory connections as compensatory strategies, though these may not fully replicate the emotional immediacy and vividness of scent-triggered recall. The loss of olfactory Proustian moments represents a genuine impairment in quality of life and emotional connection to personal history, which is one reason why anosmia is increasingly recognized as a significant medical condition rather than a minor inconvenience.

Why do certain smells trigger memories but others don’t?

Not all smells have equal power to trigger Proustian moments, and several factors determine whether a particular scent becomes an effective memory cue. The most powerful smell-memory associations form when the scent is present during emotionally significant experiences—moments of strong positive or negative emotion, important life transitions, formative experiences, or times of particular sensitivity or openness. A smell encountered during routine, neutral experiences typically doesn’t form strong memory associations because the experience itself isn’t strongly encoded. The emotional arousal during the original experience essentially tells your brain “this is important, remember this,” and any sensory information present—including smell—gets incorporated into that memory trace. The specificity and distinctiveness of the smell matters enormously. Common smells you encounter constantly don’t serve as specific memory markers because they’re associated with too many different contexts and time periods. The smell of coffee, for instance, is unlikely to trigger a specific childhood memory if you’ve been drinking coffee daily for decades—it’s too generically distributed across your life to point to any particular moment. However, a very specific scent that was common in your childhood home but rarely encountered since—perhaps a particular cleaning product, a specific flower, or an unusual food—maintains its connection to that specific time and place. When you finally encounter it again years later, it hasn’t been overwritten by new associations and can trigger those older memories. The timing of the original memory formation influences later recall power. As mentioned, childhood and adolescent experiences appear particularly susceptible to later Proustian recall, possibly because the developing brain encodes sensory-emotional associations differently, or because formative years involve more “first time” experiences that are inherently emotionally charged and thus more strongly encoded. Personal relevance matters too—smells associated with personally significant people, places, or events in your unique life history become powerful memory triggers for you specifically, while those same smells might be neutral or trigger completely different memories in someone else. This is why Proustian moments are so idiosyncratic and personal. Finally, some smells may be inherently more memorable or emotionally evocative for evolutionary reasons—research suggests smells associated with food, danger, or mates may have evolutionary significance that makes them more strongly encoded and more powerful as memory triggers across human populations.

Can traumatic memories be triggered by the Proust Effect?

Yes, absolutely, and this represents one of the most challenging aspects of scent-triggered memory. While popular discussions of the Proust Effect often focus on pleasant nostalgic memories, the same mechanism that brings back happy childhood moments can also trigger traumatic memories with equal or greater intensity. For people with PTSD or who have experienced significant trauma, olfactory triggers can produce sudden, overwhelming re-experiencing of traumatic events—not just remembering that something bad happened, but feeling transported back into the traumatic moment with full sensory and emotional intensity. This happens because trauma memories are often encoded with particularly strong emotional arousal, and any sensory information present during the trauma—including smells—can become powerful triggers for intrusive memories. The direct connection between olfactory processing and the amygdala means that smells can activate trauma memories and associated fear responses immediately and automatically, often before conscious awareness or cognitive control can engage. Veterans with PTSD might be triggered by smells associated with combat—gasoline, smoke, certain foods, body odors. Survivors of assault might be triggered by a perpetrator’s cologne or by smells associated with the location where trauma occurred. Accident survivors might be triggered by smells of medical environments, burning rubber, or other accident-related odors. These scent-triggered trauma memories can feel overwhelming precisely because they have the characteristic Proustian quality of immediacy and re-experiencing rather than distanced remembering—the person doesn’t just remember the trauma, they feel as though it’s happening again. This is one reason trauma treatment often includes addressing sensory triggers, including olfactory ones. Exposure therapy might gradually desensitize people to triggering smells in safe contexts. Understanding that smell is a potential trigger helps trauma survivors and their support systems make sense of seemingly inexplicable reactions—a panic attack triggered by a perfume someone is wearing, distress when walking past a restaurant, or avoidance of certain environments based on associated smells. On the other hand, some therapeutic approaches are exploring whether positive scent associations might be used therapeutically to access pre-trauma resources or create new, safe associations that compete with traumatic smell-memory pairings, though this requires careful professional guidance. The power of the Proust Effect cuts both ways—it can bring joy and connection to positive pasts, but it can also bring unwanted, intrusive re-experiencing of traumatic pasts, highlighting why understanding and managing sensory triggers is crucial for trauma recovery.

By citing this article, you acknowledge the original source and allow readers to access the full content.

PsychologyFor. (2025). Proust’s Madeleine Effect: What it Is, Characteristics and Causes. https://psychologyfor.com/prousts-madeleine-effect-what-it-is-characteristics-and-causes/