Born in Florence, where he worked all his life (except for a short Roman period where, under the orders of Sixtus IV, he executed some of the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel), Sandro Botticelli is one of the most famous painters of the Italian Quattrocento. The works that he has left us not only contain unparalleled beauty and refinement (product of the perfect fusion of Gothic delicacy and Renaissance forcefulness), but they entail a philosophical meaning that can only be understood in the context of an era. : humanism.

We propose below a journey through the life and works of Botticelli famous painter of the Italian Renaissance.

Brief biography of Sandro Botticelli

Perhaps many do not know that Sandro Botticelli’s real name was Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi; “Botticelli” is just his nickname. Now, where this trailer comes from remains a mystery. Some authors maintain that young Sandro inherited it from his older brother (who was no less than 25 years older than him and who, in fact, became his guardian given the advanced age of his parents).

It seems that Antonio, the brother, was large, so people knew him as “botticello”, “tonelete” in Italian. Another version says that the brother was a batifolia by trade, that is, he dedicated himself to making gold and silver leaf to gilt or silver objects, and that the young Sandro got his nickname from this nickname. This second version does not seem far-fetched, since the batifolia version was also one of our artist’s first dedications.

Be that as it may, the man known as Sandro Botticelli was born in Florence in the year 1444 or 1445, if we take into account a document from 1458 in which his father, Mariano di Vanni di Amedeo Filipepi, argues that his son Sandro was 13 years old. Not much is known about these early years; Probably, and as we have already mentioned, Sandro helped his brother in the job. In 1460, When the young man is about 15 years old, we already find him in the “bottega” or workshop of the painter Filippo Lippi , who will be his teacher for seven years and whose son, Filippino Lippi, will be a future disciple of Botticelli himself. What things are…

The forging of an artist

In 1467 we already find a young Sandro working side by side with Andrea Verrocchio, one of the great Florentine painters of the Quattrocento. It seems that his work was more a collaboration as an associate than as an apprentice, a fact that fits if we take into account that, at that time, Botticelli was already 22 years old.

In Verrocchio’s workshop we also found a very young Leonardo da Vinci In fact, the famous canvas The Baptism of Christ, from Andrea Verrocchio’s workshop, features an angel in profile whose authorship experts do not hesitate to attribute to Da Vinci; What is not said is that, probably, practically the rest of the work is due to Botticelli’s brush.

Later, Sandro enters the workshop of Antonio Pollaiuolo (Verrocchio’s well-known rival), from whom he learns the nude technique. It is with him that he made one of his best-known early works: in 1469, the Tribunale della Mercanzia, which judged commercial disputes, commissioned Pollaiuolo to create a series of paintings for the backs of the judges’ chairs. These paintings were to represent the 7 virtues, namely: faith, hope, charity, strength, justice, prudence and temperance.

For unknown reasons, Pollaiuolo could only take charge of 6, so the execution of the remaining virtue fell into the hands of a young Sandro. Botticelli represents Fortitudo (strength) like an imposing matron of clean volumes, framed by entirely convincing architectural motifs that attest to the young painter’s knowledge of the latest developments in perspective. For many, even his contemporaries, the Strength of Botticelli has an evidently greater quality than the other virtues executed by his colleague.

The definitive takeoff of the young artist occurred around 1470, when he began to run his own workshop. The fame he has achieved with his Strength precedes him; Soon the Medici, the rich family that dominates the city of Florence, notice him and begin to commission him to work. This will be the beginning of the golden period of Sandro Botticelli

The Medici and Neoplatonism in painting

Little by little, Botticelli entered the Florentine cultural world. Sensitive and with a restless mind, the young He is impressed by the philosophical precepts of the moment, championed by the Florentine Neoplatonic Academy, encouraged by the same Medici family Florence is a prosperous and refined city where a new thought is bubbling: humanism. The topic was not new; Since the 14th century, there has been a rise in humanist thought, with such outstanding authors as Dante and Petrarch. But, of course, it will be the 15th century, the Italian Quattrocento, that will witness the definitive takeoff of this way of seeing the world and existence.

Florentine artists and intellectuals at the end of the 14th century were aware that they were experiencing a change Or, at least, what they considered as such. They believed themselves to be protagonists of a great renewal classical, that is, the definitive recovery of the classics of Antiquity (although, in truth, the Middle Ages never forgot the Greeks and Romans, but that is another story). Thus, an enormous interest in classical literature (Ovid, Virgil…), as well as in Greek and Roman historiography (Livy, Herodotus…) and, of course, in philosophy, led by great names such as Aristotle, arose in Florence. and Plato.

What does all this have to do with Sandro Botticelli? We have already said that his main patrons in the 1470s and 1480s were the Medici. And the Medici were the great architects of this renewal classic. The great intellectuals of the time moved around him, such as Marsilio Ficino, Cristoforo Landino and Angelo Poliziano. In 1459 it had been founded the Florentine Academy of Medicine, the true epicenter of all humanist knowledge of the time And Sandro Botticelli was going to be in charge of transferring his entire philosophical arsenal to painting.

The great works of art

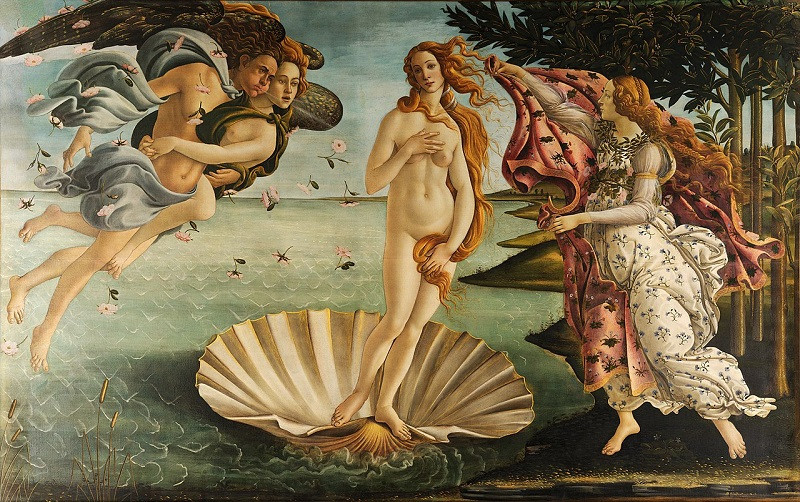

From this flourishing period are works of the stature of Spring (1482), Venus and Mars (1483), Minerva and the centaur (1482) or the famous The birth of Venus (1485). Let’s pause for a moment on some of these works to understand why Sandro Botticelli’s painting represented the humanistic ideal of the Medici.

Marsilio Ficino, the great Florentine philosopher of the Quattrocento, attempted to unite Platonic concepts with Christianity Thus, the ideas would be of a spiritual nature, which elevates us towards divinity, while all bodily desires would be linked to the lowest part of the human being. In some way, in all the paintings we have cited, Botticelli captures these neoplatonic ideas of Ficino. In Minerva and the centaur, for example, would represent the triumph of pure love, represented by the goddess, against the lust of the centaur. Minerva grabs him by her hair, emphasizing her undeniable power. On the other hand, in Venus and Marsthe god of war appears asleep and vulnerable under the watchful gaze of the goddess of Love.

The Neoplatonic ideology is even clearer in the painter’s two most famous paintings: Spring and The Birth of Venus. The sinuous naked body of the Venus that is born from the sea (in the second work), is directly inspired by the classical Venuses (especially the modest Venuses of Praxiteles, who cover their breasts and genitals), and constitutes, by the way, , the first almost life-size nude since ancient times. It is commonly accepted that the face of Venus is that of Simonetta Vespucci, the young Florentine beauty who died of tuberculosis at the age of 23, and whom Botticelli deeply admired.

It seems that Botticelli could have been inspired by the famous Theogony by Hesiod , where the sea birth of the goddess is recounted. This birth is peculiar; Venus/Aphrodite is born from the union of the severed genitals of the god Uranus and the foam of the sea. Pico della Mirandola, another of the intellectuals of the time, affirms that the union of the divine semen with formless matter gives rise to a beautiful and pure being, the celestial Venus. This links directly with the aforementioned Neoplatonic theories, since there would be a simile between the semen of the god (the celestial ideas) and the matter (the sea water), whose union is necessary to give rise to the Good (the celestial Venus). .

It is important to highlight at this point that nudity had, for humanists, an absolutely different meaning than that which was later given to it with the Protestant Reformation and the consequent Catholic Counter-Reformation. Nudity, since the Middle Ages, was a symbol of purity , since we are born naked and Adam and Eve were naked in Paradise. For this reason, the Venus that is born in Botticelli’s painting is not a lascivious Venus, but a pure one, and that is why she modestly covers her breast and genitals. On the contrary, the Venus in the painting Spring is fully dressed (with the cloak that, by the way, is extended to her by the figure of the Hour in the previous painting). In other words, the celestial Venus has materialized; ideas have taken shape on earth.

dark times

In 1491, an enigmatic character took power in Florence: the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola The rise of such a gloomy character means the fall of Florentine humanism and the Academy, and a severe theocracy is imposed that condemns all “sinful” works and objects that “incite” sin. On Carnival Tuesday in 1497, a huge bonfire was raised in Florence, which history has called the Bonfire of the Vanities, where the Florentines, spurred on by the friar, burned pictures, books, oils, perfumes and jewels; everything that, supposedly, could distance them from the path of Christian virtue.

Savonarola’s preaching leaves an indelible mark on Botticelli’s nervous and sensitive character, to the point that he will never be the same again. Or, at least, not his works. The spiritual anxiety that the artist experiences with the Dominican’s harangues leads him to participate in the burnings.

Some authors have pointed to the painter’s supposed homosexuality as a trigger for his feeling of guilt (remember that, for the Church of the time, homosexuality was a great sin, called sodomy). Be that as it may, Botticelli lived through some turbulent years. Even after the fall and subsequent execution of the friar and the restoration of order in Florence, Sandro will continue to be possessed of a strange religious exaltation, which works such as his strange mystical nativity executed once Savonarola disappeared.

Although his star remained more or less bright (at the beginning of the 16th century he was appointed one of the juries that had to decide the location of the David by Michelangelo), Botticelli is aware that his time has passed. The new style, the new maniera (championed by artists such as Leonardo, Raphael or Michelangelo himself) has made its language obsolete, halfway between the beautiful and stylized international Gothic and the more forceful Renaissance. With his death, which occurred in 1510, the work of Sandro Botticelli was forgotten, which would not be recovered until the 19th century, at the hands of the Pre-Raphaelites and Nazarenes.