Art is as old as human beings. And, although painting is often considered one of the first vehicles of artistic expression, in reality the sculptural testimonies are not that far apart in time, so we can consider that human beings began to sculpt at the same time as they painted.

In fact, until not many centuries ago the phenomenon of sculpture could not be separated from painting, since the works were completely polychrome. This is true even in ancient Greece; Although it may seem strange to us, classical sculptures were not shown with the white of marble, but were covered with layers of pigments. A sculpture was not considered finished until it was properly painted.

Beyond this, each culture and each era has had its own form of expression, logically. Art is one of the main vehicles through which ideas and social customs are manifested, which is why sculpture is also connected to the different eras and cultures that have occurred in history. In today’s article we are going to take a tour of 10 of the best-known sculptural works in the history of art.

The great sculptures of history

The history of art is, of course, very extensive and complex. To compose the list that we present, we have tried to choose works from different periods, with the aim of designing a brief but intense tour through the history of sculpture. We hope you like it.

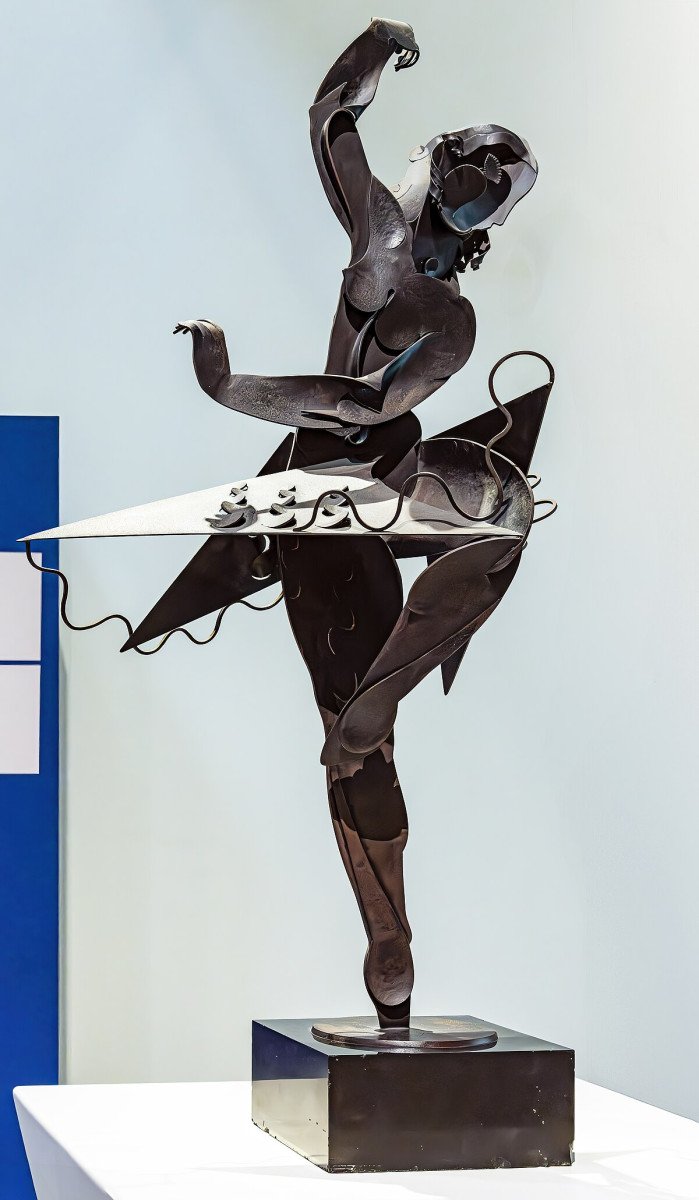

1. Seated scribe (Cairo Museum, Egypt)

Made of limestone in the Old Empire (approximately around 2500 BC) the Seated Scribe in the Cairo Museum (Egypt) is a perfect example of the type of sculpture intended for royal tombs or important figures.

The Egyptians believed that, once in the afterlife, they would continue to lead a life as similar to the one they had enjoyed on earth. Therefore, The deceased were buried with all the necessary belongings, elements that also included people at their service, such as dancers, wine pourers or, as in the case at hand, notaries.

The surprising realism of this small sculpture (51×41 cm) lies in the position of the scribe who, with his legs bent, gives movement to the figure. On the other hand, the rock crystal that fills the eye sockets gives, with its brilliance, a remarkable depth to the gaze.

2. Aphrodite of Cnidus, by Praxiteles (Vatican Museums, Rome)

As is often the case with Greek art, the vast majority of works by Praxiteles (400 – 320 BC) are preserved thanks to the copies made by the Romans. This is the case of his famous Aphrodite, made for the temple of Cnidus (Anatolia), which shows the goddess leaving the bath (or entering), completely naked. Although Aphrodite modestly covers her genitals, if we believe what Pliny the Elder tells us, the first recipients of the sculpture, the inhabitants of Kos, rejected it as “immodest.” It seems that the citizens of Cnidus were not in such a hurry to acquire it.

The famous Aphrodites of Praxiteles constitute the first representations of the naked female body. Contrary to what is often believed, during the first millennia of history the male nude was much more abundant, especially in Greece, where women lived secluded in the gynoecium and absolutely isolated from public life, with the sole exception of the hetairas or prostitutes. By the way, it is believed that the model for this Aphrodite was Phryne, the famous courtesan who drove the jury who wanted to put her to death mad with love.

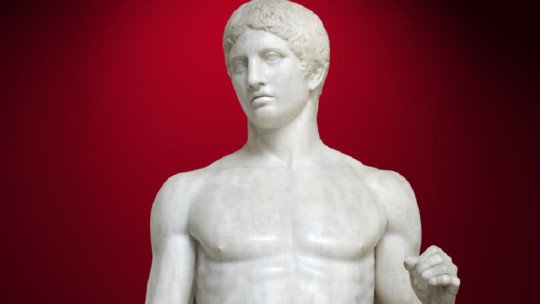

3. Augustus of Prima Porta (Vatican Museums, Rome)

This beautiful sculpture, found in the ruins of the Villa of Livia (the wife of Augustus) in Prima Porta (Rome), reflects the canons of the Greek sculptor Polycletus, which he already captured in his famous Doryphorus (5th century BC). Here, the Roman artist (unknown, by the way) uses the well-known canon of the seven heads, as well as the slight contrapposto that we can also observe in the Greek Doryphorus.

Augustus finally ascends to power after a long civil war and after the final fall of the Roman Republic. The sculpture of Prima Porta must be framed in the complex propaganda message of the emperor, very interested in appearing as the great victor of the conflict and, above all, as the peacemaker of the newborn empire. Thus, not only does he place a dolphin and a cupid at his feet (symbols of Venus, from whom his family supposedly descends) but he also introduces various significant elements into the armor: the chariot of Helios, the sun-god (symbol of his power) or the figure of Tellus (the earth) with the horn of plenty (in reference to the fact that peace brings wealth).

4. The Majestat Batlló (National Museum of Art of Catalonia, Barcelona)

The quintessential image of the Romanesque Crucified, the Majestat Batlló (12th century) shows us a Christ triumphant over death, from whom not a single drop of blood emanates. Characteristic of the first medieval centuries is the representation of Jesus nailed to the cross with four nails (and not three, as will become common later), fully dressed and with a serene face that does nothing to foreshadow the approach of death. The idea that is expressed is that of a Christ who transcends the human condition and rises above any type of passion.

As was the case in ancient times, during the Middle Ages a sculpture was not considered finished if it was not painted. In the case of this Majestat, the beautiful polychrome, based on strong primary tones, is still perceived in the wood; The red tunic of the Crucified stands out, long to the feet and decorated with geometric figures of an intense blue.

5. The White Virgin, Toledo Cathedral (Spain)

In the Gothic centuries something begins to change. The once hieratic wooden virgins, whose function was limited to being the throne for their son (sitting on their lap), now become true mothers. In this way, the representations of the Virgin in the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries are humanized, they turn towards the Child and play with him.

As happens in all eras, art reflects the changes in society. And the fact is that the Gothic society is not the same as the one that had given birth to the Romanesque style: the incipient humanism (flagged by cities like Chartres) and the rise of commerce contribute to the rise of the towns and, therefore, to a significant change in people’s conception of God.

In this period, representations of Mary holding the Child proliferated and, in the vast majority, the young mother looks smiling at her little one. That of the Toledo Cathedral is especially significant for the sweetness that comes from the Virgin’s gaze, as well as her broad smile and the affectionate gesture of the Child, who touches her chin. Likewise, the clothing, tremendously realistic, predicts a new naturalism, already far removed from the medieval concept of representation.

6. Michelangelo’s David (Accademia Gallery, Florence)

It is the most famous sculpture by Michelangelo and, possibly, in the world. The David represents the apotheosis of the Florentine Renaissance of the 16th century; Commissioned in 1501 by the Republic of Florence, it was intended to be part of a sculptural group that, in principle, was going to be located in the highest part of the city’s Duomo.

For the execution of the work, Michelangelo was given a block of marble that had already been used previously by other artists, which did not please the sculptor at all, since he was used to choosing the stones himself, in the quarry itself. marble pieces. This may be precisely what explains the various anatomical disproportions of the David, if we consider that Michelangelo had to adapt to the block already used.

Despite this, the sculpture masterfully captures the naked male body, and captures the moment when David, the biblical hero, is about to face the giant Goliath, a perfect metaphor to represent the newborn Florentine Republic. The frown of the young man, whom Michelangelo conceived as much more athletic and muscular than his predecessors (see, for example, Donatello’s David), indicates the moment in which David puts his full attention on what is going to happen.

7. The Abduction of Proserpina, by Bernini (Borghese Museum, Rome)

The incomparable Gian Lorenzo Bernini, a true reference of Baroque sculpture, displays all his mastery in this work. The serpentine line that twists the figures reminds us of a distant mannerism, but the expression and dynamism are typically baroque.

Bernini captures the moment when Pluto, the Greek Hades, kidnaps Proserpina, the daughter of the goddess Ceres, to take her to his infernal world. In the girl’s gesture we can see the terror that she is feeling: with one hand she tries to push the abductor away, while, at the same time, she contorts her entire body in an attempt to escape.

Proserpina’s face, which raises her eyes and opens her mouth in what seems like a scream, has the theatricality typical of the baroque style. On the other hand, Bernini’s mastery is especially appreciated in Pluto’s hand, which sinks into the young woman’s flesh and, for a few moments, makes us forget that what we are contemplating is just a cold block of marble.

8. Eros and Psyche, by Antonio Canova (Louvre Museum, Paris)

If Jacques-Louis David was one of the great standard-bearers of pictorial Neoclassicism, Antonio Canova (1757-1822) was undoubtedly one of the champions of sculpture. His Eros and Psyche captures with extreme delicacy the moment in which the mortal Psyche is rescued from her eternal sleep by the kiss of the god Eros, according to the text of Apuleius.

The composition is designed in the shape of a large X formed by the outstretched wings of Eros (Cupid for the Romans), his legs and the outstretched body of Psyche. The position of the young woman, who raises her arms to embrace her lover while tilting her head, is not at all forced in the hands of Canova, who achieves with this sculpture one of the apotheosis of Neoclassical art.

9. The Grand Waltz, by Camille Claudel (Rodin Museum, Paris)

In 1893, Camille Claudel (1864-1943) presented her work The Great Waltz at the French National Salon of Fine Arts, which represents a couple of dancers captured in the middle of dancing. The distinguished student of Auguste Rodin, who surpassed the master, manages to capture in bronze the subtle and graceful movement of bodies and clothes, which fly and swell with the turns.

The male figure is completely naked, while the woman is covered with a dress that Camille manages to make vaporous. The result is a work of high erotic charge and unparalleled beauty, of surprising delicacy and exquisiteness.

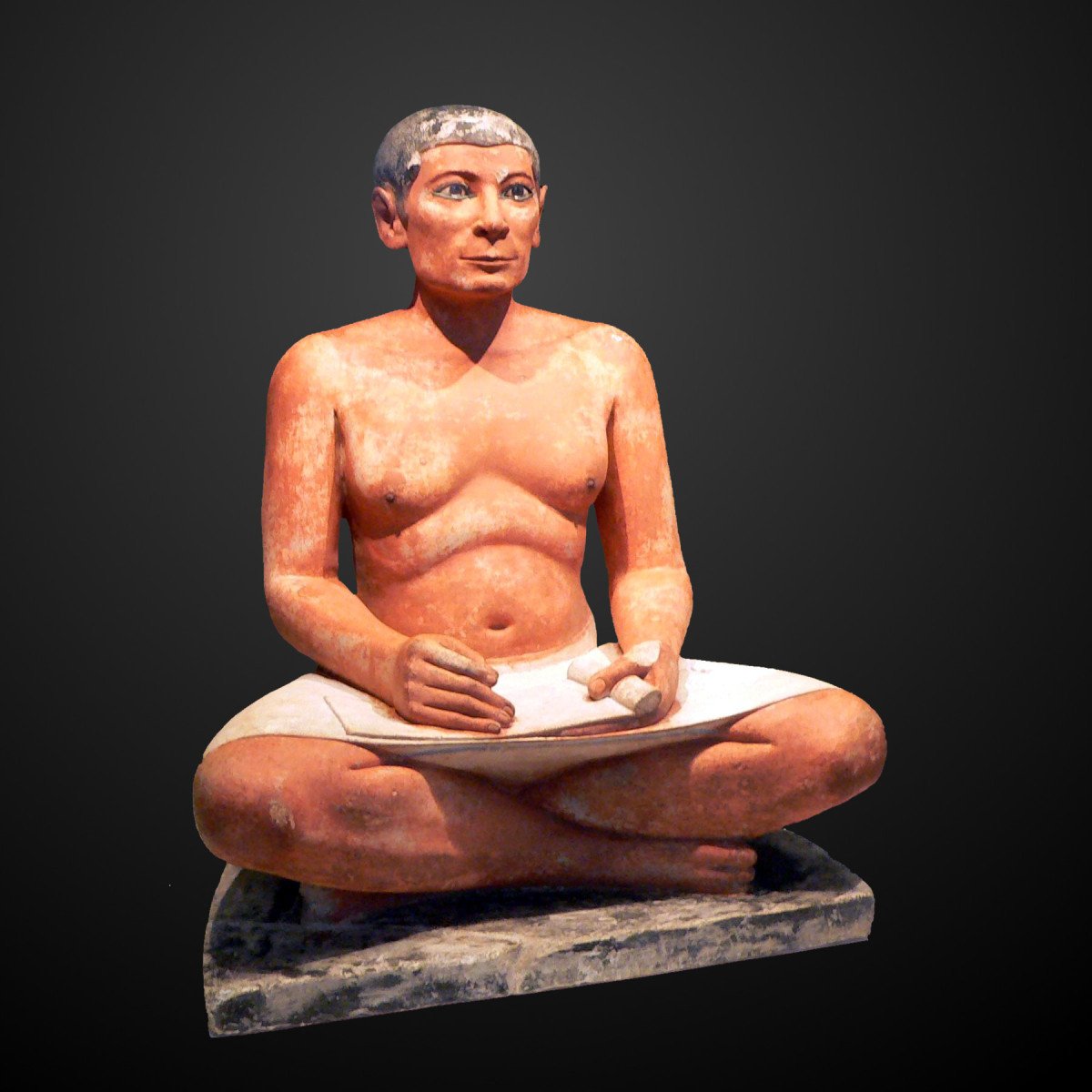

10. Great dancer, by Pablo Gargallo (various locations)

There are up to three versions of this work by Pablo Gargallo (1881-1934), possibly one of the most beautiful of his entire artistic corpus. The sculpture represents a dancer at the moment of executing one of her steps; Gargallo creates the composition using assembled iron plates, which gives the piece a unique and strange beauty.

The Great Dancer belongs to the period in which Gargallo began to experiment to find a language that was his own. In this sculpture we see traces of naturalistic representation, but also of the cubism prevailing at the time, without forgetting that the artist is already incorporating emptiness as a sculptural component, something that sculptors like Jorge Oteiza will take much further with his “metaphysical boxes.”