Viruses and bacteria often cause similar clinical symptoms in affected patients.

Various studies indicate that this may be due, in part, to the fact that the cellular immune responses to both pathogens share various similarities. Even so, the treatments for an infection of viral or bacterial origin are very different, so knowing the differences between viruses and bacteria is essential

Despite both being considered microscopic organisms potentially pathogenic to humans, other animals and plants, there are many more factors that differentiate them than qualities that unify them. Here we show you some of the most important differentiating characteristics between viruses and bacteria.

Main differences between viruses and bacteria: a question of microscopy

Before addressing the many differences between these microorganisms, It is always good to remember the attributes that unify them Some of them are the following:

All these similarities are very superficial , because as we will see below, the differentiating elements are much more numerous. We explore them below.

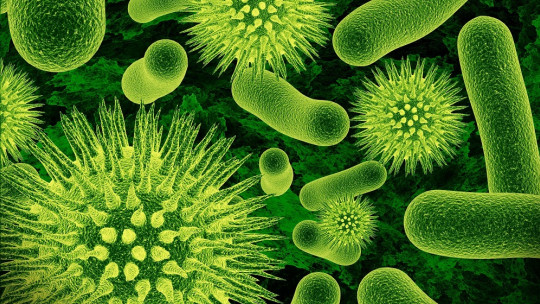

1. Morphological differences

The differences between viruses and bacteria are so abysmal that there is a hot debate in the scientific community, since There is no doubt that bacteria are living beings, but this cannot be stated if we talk about viruses

In general, various investigations conclude that viruses are structures of organic matter that interact with living beings, but that they are not biological forms in themselves. Because?

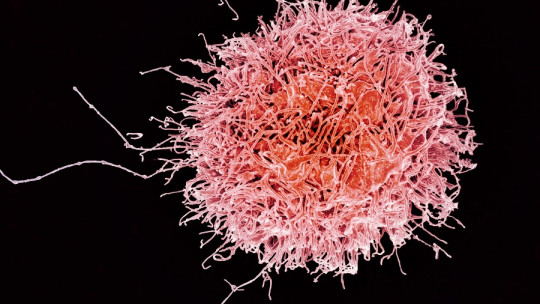

1.1 Acellularity

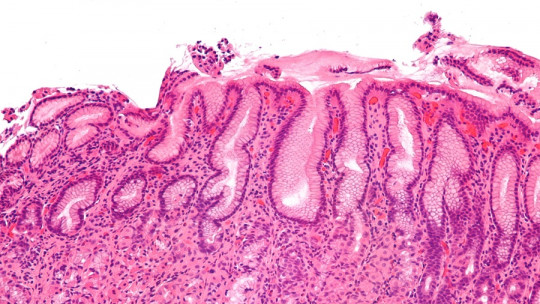

According to the definition of official organizations, a cell is a “fundamental anatomical unit of all living organisms, usually microscopic, formed by cytoplasm, one or more nuclei and a membrane that surrounds it.”

This requirement is fulfilled by bacteria , because although they only have one cell that makes up their entire body, it has all the requirements to be considered a living form. The bacterial cell is made up of the following elements:

All of these characteristics are common to the complex cells that make up eukaryotic organisms, but for example, bacteria lack mitochondria, chloroplasts, and a delimited nucleus. Speaking of nuclei and genes, These microorganisms have their genetic information in a structure called a nucleoid which consists of a double strand of circular free DNA closed by a covalent bond.

As we have seen, bacteria have a unicellular structure that is not as complex as the cells that make up us, but it does not fall short biologically speaking. In the case of viruses, we have much less to tell:

So that, The structure of viruses does not meet the requirements to be considered a cell If this is the minimum basis of any living being, are viruses biological organisms? Due to its acellularity, in a strict sense we can say no.

1.2 Morphological diversity

Due to its greater biological complexity, Bacteria come in a wide variety of shapes Some of them are the following:

- Coconuts, spherical in shape. Diplococci, tetracocci, stretococci and staphylococci.

- Bacilli, rod-shaped.

- Spiralized bacteria. Spirochetes, spirilli and vibrios.

In addition, many bacteria have flagellar structures that allow them to move through the environment. If they have a single flagellum they are called monotric, if they have two (one at each end) lophotric, if they have a group at one end amphitric, and if they are distributed throughout the body, peritrich. All this information highlights the bacterial morphological diversity.

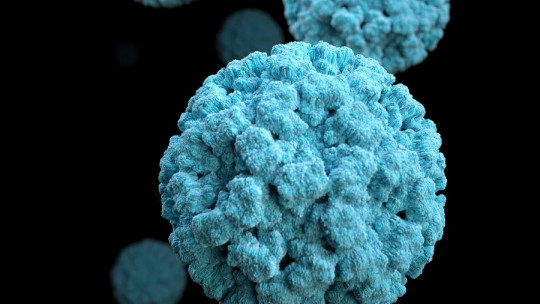

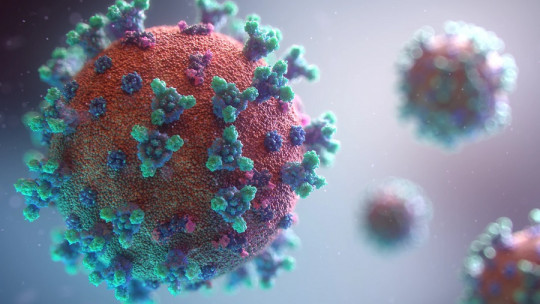

When referring to viruses, we find, once again, a much more desolate structural landscape There are helical, icosahedral, enveloped shapes, and some with slightly more complex shapes that do not fall into any of the previously mentioned groups. As we can see, its morphology is very limited.

- You may be interested: “The 3 types of bacteria (characteristics and morphology)”

2. A differential reproductive mechanism

Perhaps the greatest difference between viruses and bacteria is their way of infecting the host and multiplying within it. Next, we do not plunge into the world of the reproduction of these microorganisms.

2.1 Bipartition

Bacteria, both free-living and pathogenic, usually reproduce asexually by bipartition The complete genome of the cell replicates itself exactly before each reproductive episode, since unlike eukaryotic cells, bacteria are capable of replicating all of their DNA throughout the cell cycle autonomously. This happens thanks to replicons, units with all the information necessary for the process.

To keep things simple, we will simply say that the cytoplasm of the bacteria also grows, and when the time comes, a division occurs in which the mother bacteria splits into two, each with a genetically identical nucleoid.

2.2 Replication

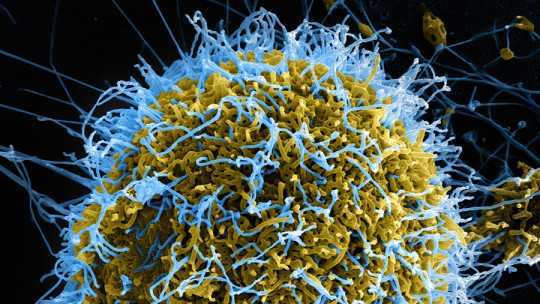

For viruses to multiply, the presence of a eukaryotic cell that they can hijack is essential Viral replication is summarized in the following steps:

- Adhesion of the virus to the cell it is going to infect.

- Penetration, entry of the pathogen into the host cell by a process of endocytosis (viroplexy, typical penetration or fusion).

- Denudation, where the virus capsid degrades, leaving the genetic information free.

- Replication of the genetic information of the virus and synthesis of its proteins, hijacking the biological mechanisms of the infected cell.

- Assembly of the viral structure within the cell.

- Release of new viruses through cell lysis, breaking its wall and killing it.

The replication of the genetic information of the virus is very varied, since It depends a lot on whether it is composed of DNA or RNA The essential idea of this entire process is that these pathogens hijack the mechanisms of the infected host cell, forcing it to synthesize the nucleic acids and proteins necessary for its assembly. This reproductive difference is essential to understanding viral biology.

3. Diverse biological activity

These differences between viruses and bacteria when it comes to reproduction, condition the biological niches in which both microorganisms develop

Bacteria are prokaryotic organisms that can be parasites or free-living, since they do not require an external mechanism to multiply. In the case of pathogens, they require the environmental conditions or nutrients of the organism they invade to grow and survive.

Even so, intrinsically and theoretically, if a non-living organic medium existed with all the qualities of the infected person’s body, they would not have to invade it. This is why many pathogenic bacteria can be isolated in culture media under laboratory conditions.

The case of viruses is completely different, since their existence cannot be conceived without a cell to parasitize. Some viruses are not harmful in themselves as they do not cause harm to the host, but they all have in common the requirement of the cellular mechanism for its multiplication This is why all viruses are considered obligate infectious agents.

Conclusions

Both viruses and pathogenic bacteria are microscopic agents that can be considered germs in the strict sense of the word, since they parasitize a living being and benefit from it. Even so, in the case of bacteria there are thousands of free-living species, which also play essential roles in the biogeochemical cycles of the Earth (such as, for example, the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen).

Viruses are, on the other hand, infectious agents that in many cases are not even considered living beings. This does not mean that they do not perform important functions, since they are an essential means of horizontal gene transmission and great drivers of biological diversity. The relationship between the virus and the host is a constant biological race, since both evolve at the same time, one to infect and the other to avoid infection or combat it.

- Pitha, P. M. (2004). Unexpected similarities in cellular responses to bacterial and viral invasion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(3), 695-696.

- Betancor, L., Gadea, M., & Flores, K. (2008). Bacterial genetics. Institute of Hygiene, Faculty of Medicine (UDELAR). Topics in Bacteriology and Medical Virology. 3rd Ed. Montevideo: FEFMUR Book Office, 65-90.

- Brock, T.D., Madigan, MT, & Abad, V.T. (1993). Microbiology (No. 579.2 BRO). Mexico: Prentice Hall Hispanoamericana.

- R. Arbiza, J. Viral biology. Collected on July 11 at http://www.higiene.edu.uy/cefa/2008/BiologiaViral.pdf.

- Ruchanksy, D. Introduction to virology. Collected on July 11 at http://www.higiene.edu.uy/cefa/bacto/introvir2011.pdf.