He XVII century It starts with a scientific revolution and ends with a political revolution in England (1688) from which the modern liberal state is born. The theocratic monarchy is replaced by constitutional monarchy. Locke will philosophically justify the revolution, which places reason above tradition and faith.

The Mechanism of the 17th century: Locke and Descartes

The baroque dominates the century. The painting is filled with darkness, shadows, contrasts. In architecture, the pure and straight Renaissance lines break, they twist, the balance yields to movement, to passion. The baroque and the body. Presence of death, of the double. The difference between reality and dream. The great theater of the world, the world as representation (Calderón de la Barca). The genre of the novel is consolidated (The Quijote appears in 1605; during the 17th century the picaresque novel triumphed). In painting, Velázquez (1599-1660).

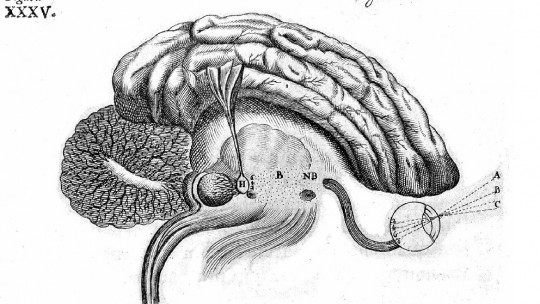

The conception of the world becomes scientific, mathematical and mechanistic. Scientists demonstrated the mechanical nature of celestial and terrestrial phenomena and even the bodies of animals (End of the Animism ).

A scientific and intellectual revolution

The scientific revolution meant moving the earth from the center of the universe. The beginning of the revolution can be dated to 1453, with the publication of the Revolution of the Celestial Orbits, by Copernicus , who proposed that the Sun, and not the Earth, was the center of the solar system. Copernicus’s physics was, however, Aristotelian, and his system lacked empirical demonstration. Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) was the most effective defender of the new system, underpinning it with his new physics (dynamics), and providing telescopic evidence that the moon and other celestial bodies were no more “heavenly” than the Earth. However, Galileo believed, like the Greeks, that the motion of the planets was circular, even though his friend Kepler demonstrated that planetary orbits were elliptical. The definitive unification of celestial and terrestrial physics occurred in 1687 with the publication of the Newton’s Principia Mathematica.

The laws of motion Isaac Newton They reaffirmed the idea that the universe was a great machine. This analogy had been proposed by Galileo and also by René Descartes, and became the popular conception at the end of this century.

As a consequence, the idea of an active and vigilant God, for whose express intention every last leaf fell from a tree, was reduced to that of an engineer who had created, and maintained, the perfect machine.

From the very birth of modern science, two conflicting conceptions have been present: an old Platonic tradition supported a pure and abstract science, not subject to a criterion of usefulness (Henry More : “Science should not be measured by the help it can provide to your back, bed and table.“). Wundt and Titchener They will be supporters of this point of view for Psychology. In this century, however, an idea of utilitarian, practical, applied science developed, whose most vigorous defender was Francis Bacon. In the following century this tradition became firmly established in England and North America, orienting itself towards anti-intellectualism.

The scientific revolution, in either conception, reissues an old atomistic idea according to which some sensory qualities of objects are easily measurable: their number, weight, size, shape and movement. Others, however, are not, such as temperature, color, texture, smell, taste or sound. Since science must be about the quantifiable, it can only deal with the first type of qualities, called primary qualities, which the atomists had attributed to the atoms themselves. Secondary qualities are opposed to primary qualities by existing only in human perception, resulting from the impact of atoms on the senses.

Psychology would be founded, two centuries later, as a study of consciousness and, therefore, included in its object all sensory properties Behaviorists later considered that the object of psychology was the movement of the organism in space, rejecting the rest. Movement is, of course, a primary quality.

Two philosophers in this century represent the two classic tendencies of scientific thought: Descartes for the rationalist vision, with a conception of pure science, and Locke for the empiricist, with a conception of utilitarian or applied science.