Many times, impressionism has been pointed out as the first “ism” that breaks with academicism. However, long before this group of rebels questioned the academic values in painting, there were other artistic currents that, with their own aesthetic ideals, advocated something similar.

It is the case of the Pre-Raphaelites, who emerged in the mid-19th century to protest against the corseted art that was taught in official schools In this article we are going to review the Pre-Raphaelite movement; We will talk about what motivated its appearance and what its essential characteristics are.

The main characteristics of the Pre-Raphaelite movement

In 1848, three fellow students and inseparable friends decided to found an artistic brotherhood. The three of them have been educated in the schools of the Royal Academy of London, in the midst of an academicism that now seems emasculating and dominating. They are young (their ages are between 19 and 23 years old) and, therefore, full of rebellion and plans for the future. Within these plans is the little less than impossible challenge of change the foundations on which Victorian art is based Almost nothing.

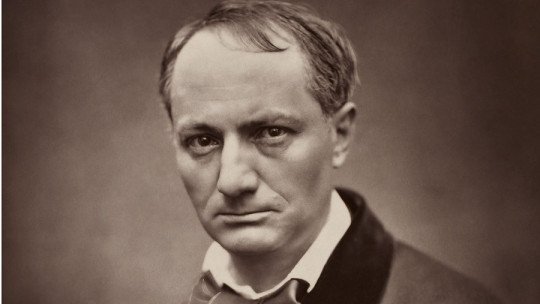

These three original members of what was called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were John Everett Millais (1829-1896), William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). The latter would later emerge as one of the most important representatives of the brotherhood, although we will see that, in the second stage of the movement, Rosetti distanced himself quite a bit from the original premises and created his own distinctive style.

It seems that the founding of the brotherhood took place in Millais’s house. There, and as Heather Birchall records in her book Pre-Raphaelites, Rossetti’s younger brother, William Michael, became secretary of the newborn brotherhood and wrote down its principles The most important of all of them was to make “good paintings and sculptures.” To do this, the Pre-Raphaelites would express “authentic” ideas, without mixing them with conventional and superfluous elements.

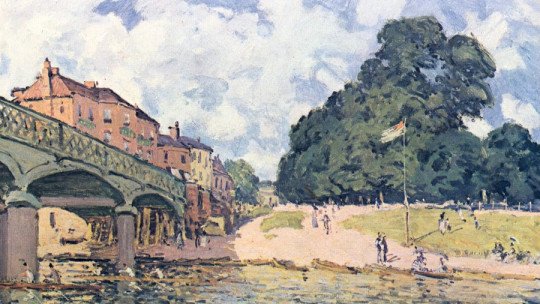

The consequence of all this is beautiful works full of detail, an authentic direct study of nature, which represented unusual or unusual themes in art. Thus, while the academy promulgated stereotyped models that followed classical ideals, the Pre-Raphaelites took their models from life, among their family and friends. Besides, They were directly inspired by nature, from which they captured each and every one of its expressions which brought them astonishingly close to the primitive Flemish people of the 15th century.

Art “before Raphael”

That was precisely the idea of these young dreamers: to passionately imitate the art that had been executed before the emergence of classicism, which they identified with figures such as Raphael or Michelangelo. For the Pre-Raphaelites, true art, that which contained that “authentic idea” that they wanted to capture, was that which had been made before these artists, whom they did not consider at any time “masters”. On the contrary; for Rossetti and company, Raphael, Michelangelo and Leonardo had corrupted art since they had subjected him to certain rules, and had thus eliminated the purity and innocence of the first Christian artists.

Whether the Pre-Raphaelites were right or not is something we will not dwell on. But we highlight this “aversion” to Rafael because, otherwise, the essence of his movement is not understood. In fact, the name of the brotherhood is already very significant: pre-raphaelitesthat is, “before Raphael.”

It is not very clear who named the brotherhood. In his autobiography, William Hunt states that he was the first to name the group with this nickname. Following Hunt again, it seems that Rossetti and Millais would have proposed the singular name of proto-Christian art, referring, once again, to Christian art prior to the 16th century.

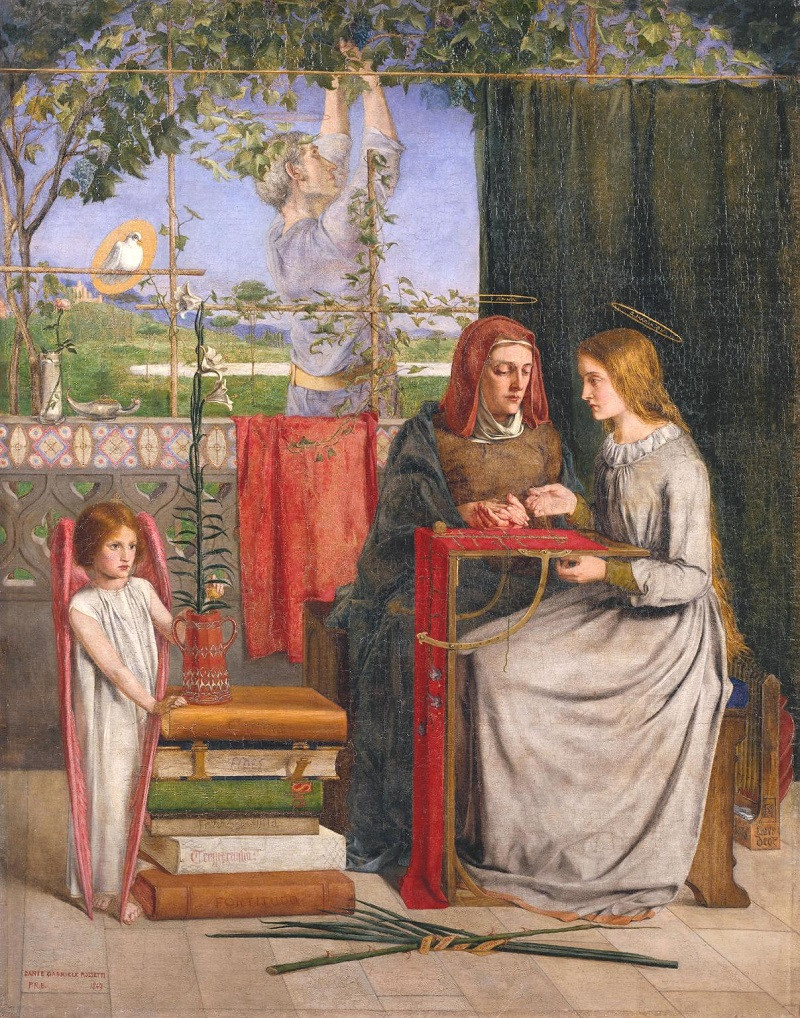

Who were the Pre-Raphaelites inspired by, then? In Italian art of the Trecento and Quattrocento , with figures such as Duccio or Fra Angelico, and also in the Flemish primitives, with Jan van Eyck at the head. He was especially touched by the lack of coherence and perspective of these paintings, as well as the detailed study of nature and the preciousness of all its details. Even the first feminine ideal of the movement was inspired, in a certain way, by the languid Gothic virgins, and would find its incarnation in the figure of Elizabeth Siddal, who would become Rossetti’s wife.

The stages of the Pre-Raphaelite movement

Two stages can be clearly seen in the trajectory of Pre-Raphaelite art. The first would cover the period 1848-1853, approximately, from the founding of the brotherhood to the split of the group. The second stage is led by Rossetti in all his splendor, and would go from the 50s of the 19th century until the painter’s death in 1882. However, it must be taken into account that the influence of the Pre-Raphaelites lasted over time. and it subjugated many artists at the end of the century, such as John William Waterhouse (1849-1917).

The initial stage: the founding of the brotherhood

We have already commented how, in 1848, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded. In 1849, Millais and Hunt managed to exhibit, for the first time, at the much hated Royal Academy. Against all odds, The works receive a fairly warm reception; its careful attention to detail and its “medievalizing aesthetics” are praised Picture Isabella by Millais, inspired by a poem by Keats (which all members of the brotherhood admired), achieves unexpected praise.

For his part, Rossetti has also begun to exhibit, but not at the Royal Academy (a fact he would always refuse), but in the so-called Free Exhibition. There he presents his painting The childhood of the Virgin, of obvious Gothic inspiration. Later, she confuses the audience with his famous Annunciation. People are not used to a representation like that: the Virgin, without anything that identifies her as a sacred character, seems like an ordinary teenager, withdrawn in her bed, scared; The archangel has his back turned, and… she has no wings!

However, the general criticism is quite favorable, which encourages the brotherhood to publish its own magazine, The germ, where its ideas about the future of art are made known. Rossetti’s sister, Christina, also writes in it, who will also be a great poet of the Victorian era.

The second stage: Rossetti’s triumph

In 1853, John Everett Millais was elected an honorary member of the Royal Academy This is a hard blow for Rossetti, who always hated the institution because he considered it the standard-bearer of artistic corseting. It is very likely that this fact greatly influenced the split of the group: in the 1850s, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood no longer existed.

The group no longer exists in a cohesive way, but its members continue working. And it is in this second stage when the work of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who is in a period of artistic fertility, will stand out powerfully. Rossetti will turn towards a much more dreamlike language, in which aestheticism, that “art for art’s sake” so characteristic of the second half of the 19th century, prevails over the previous naturalism. One of the main characteristics of this second stage, especially in Rossetti’s work, is a strong medievalism. The artist is inspired by the poetry of Dante, by the Arthurian legends, by the poems of the English romantics; the latter evoke an idealized medieval past that helps the artist escape from the modern world.

His masterpieces from this period are: Bocca Baciata (1859), Dante’s dream about the death of his beloved (1878) and, above all, his culminating work, Blessed Beatrix (1864-70), which represents Dante’s Beatrice after death, but is actually Elizabeth Siddal, Rossetti’s wife, who had died from a laudanum overdose.

The Pre-Raphaelite Muses: Lizzie Siddal and Jane Morris

The Pre-Raphaelite movement, perhaps taking the ideals from the poetry of Dante and Petrarch, configured an idealized model of feminine beauty It is mainly Rossetti who most assiduously expressed this ideal, which is irremediably linked to two of the muses of the brotherhood: Elizabeth ‘Lizzie’ Siddal (1829-1862) and Jane Burden Morris (1839-1914).

The first was “discovered” in a hat shop, and soon caught the attention of the Pre-Raphaelites for her “Gothic” beauty: tall and slender, pale, with a long swan neck and abundant reddish hair. Lizzie immediately became the sisterhood’s most sought-after muse. Famous is the episode in which she immersed herself in a bathtub to pose for the painting of Ophelia, by Millais. They say that the candles that heated the water went out, and that Lizzie caught a bad cold from staying in the icy water for so long. Starting in 1853, Rossetti wanted Lizzie all to himself. The young woman appears in many of his works, materializing that ideal of almost dreamlike beauty that the Pre-Raphaelites longed for

However, the arrival of Jane Burden changed everything. At least, for Lizzie. Much younger than her and equally beautiful, Jane was serious competition. Her beauty, however, could not be more different: while Lizzie was an almost ethereal figure, Jane had a forceful, dark beauty, with abundant black, curly hair.

The Pre-Raphaelites met her one night at the theater and immediately fell in love with her. William Morris (who, along with Edward Burne-Jones, had entered the group during the second stage) fell madly in love with her. The two married in 1859, although it seems that Jane, ‘Janey’, as she was called, only had eyes for the handsome Rossetti. Soon, the young brunette displaces the pale redhead as the group’s muse.

Jane’s presence plunged Lizzie further into her depression, which had begun in 1861, when she gave birth to a stillborn baby. Rossetti’s constant infidelities did not help. Thus, on the morning of February 11, 1862, Lizzie was found dead in her bed. She had taken an overdose of laudanum; It is still unknown today whether it was accidental or a suicide.

Rossetti, devastated, buried his unpublished poems with her. Years later he would repent and order his wife’s coffin to be exhumed to recover them. Her luck was not much better than his; Driven by drugs and alcohol, Rossetti died in 1882, aged 53.