In philosophy of science, The problem of demarcation refers to how to specify what the limits are between what is scientific and what is not

Despite the age of this debate and the fact that a greater consensus has been gained as to what the bases of the scientific method are, to this day there is still controversy when it comes to delimiting what a science is. We are going to see some of the currents behind the problem of demarcation, mentioning its most relevant authors in the field of philosophy.

What is the demarcation problem?

Throughout history, human beings have been developing new knowledge, theories and explanations to try to describe natural processes in the best possible way However, many of these explanations were not based on solid empirical bases and the way in which they described reality was not entirely convincing.

That is why in several historical moments the debate has been opened about what clearly delimits a science from what is not. Nowadays, although access to the Internet and other sources of information allows us to quickly and safely know the opinion of people specialized in a topic, the truth is that there are still many people who follow positions and ideas that were already discarded ago. many years, such as the belief in astrology, homeopathy or that the Earth is flat.

Knowing how to differentiate between what is scientific and what appears to be scientific is crucial in several aspects. Pseudoscientific behaviors are harmful both to those who believe them and to their environment and even to society as a whole

The movement against vaccines, who defend that this medical technique contributes to children suffering from autism and other conditions based on a global conspiracy, is the typical example of how pseudoscientific thoughts are seriously harmful to health. Another case is the denial of human origin in climate change, causing those who are skeptical of this fact to underestimate the harmful effects of global warming on nature.

The debate of what science is throughout history

Below we will see some of the historical currents that have addressed the debate about what the demarcation criterion should be.

1. Classic Period

Already in the time of Ancient Greece there was interest in delimiting between reality and what was subjectively perceived. A distinction was made between true knowledge, called episteme, and one’s own opinion or beliefs, doxa

According to Plato, true knowledge could only be found in the world of ideas, a world in which knowledge was shown in the purest form possible, and without the free interpretation that human beings gave of these ideas in the real world. .

Of course, at this time science was not yet conceived as we do now, but rather the debate revolved around more abstract concepts of objectivity and subjectivity.

2. Crisis between religion and science

Although the roots of the demarcation problem go deep into the classical era, It was in the 19th century that the debate gained real strength Science and religion were differentiated more clearly than in previous centuries, and were perceived as antagonistic positions.

Scientific development, which tried to explain natural phenomena by disregarding subjective beliefs and going directly to empirical facts, was perceived as something that declared war on religious beliefs. A clear example of this conflict can be found in the publication of The origin of speciesby Charles Darwin, which generated a real controversy and dismantled, under scientific criteria, the Christian belief in Creation as a voluntarily guided process from a form of divine intelligence.

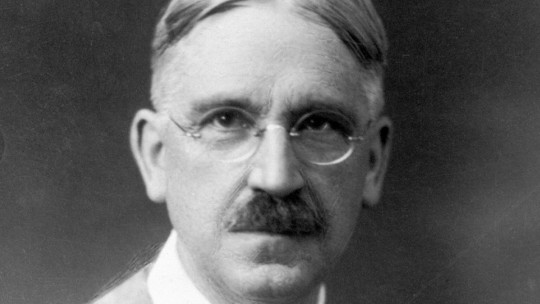

3. Logical positivism

At the beginning of the 20th century, a movement emerged that sought to clarify the boundary between science and what it is not. Logical positivism addressed the problem of demarcation and proposed criteria to clearly delimit that knowledge that was scientific from that which pretended to be so or pseudoscientific.

This current is characterized by giving great importance to science and be contrary to metaphysics, that is, that which is beyond the empirical world and that, therefore, cannot be demonstrated by experience, as the existence of God would be.

Among the most notable positivists we have Auguste Comte and Ernst Mach. These authors considered that a society will always achieve progress when science is its fundamental pillar. This would mark the difference between previous periods, characterized by metaphysical and religious beliefs.

The positivists considered that For a statement to be scientific it had to have some type of support, either through experience or reason The fundamental criterion is that it had to be verifiable.

For example, proving that the Earth is round can be verified empirically, by going around the world or taking satellite photographs. In this way, you can know if this statement is true or false.

However, positivists considered that empirical criteria were not sufficient to determine whether something was scientific or not. For the formal sciences, which can hardly be demonstrated through experience, another demarcation criterion was necessary. According to positivism, this type of science were demonstrable in case their statements could be justified by themselves that is, they were tautological.

4. Karl Popper and falsificationism

Karl Popper considered that for science to advance it was necessary, instead of looking for all the cases that confirmed a theory, look for cases that refute it This is, in essence, his criterion of falsificationism.

Traditionally, science had been done based on induction, that is, assuming that if several cases were found that confirmed a theory, it had to be true. For example, if we go to a pond and see that all the swans there are white, we infer that the swans are always white; but… what happens if we see a black swan? Popper considered that this case is an example that science is something provisional and that, If something is found that refutes a postulate, what is given as true would have to be reformulated

According to the opinion of another philosopher before Popper, Emmanuel Kant, one should take a neither very skeptical nor dogmatic view of current knowledge, given that science assumes more or less secure knowledge until it is disproved. Scientific knowledge must be able to be tested contrasted with reality to see if it fits with what experience says.

Popper considers that it is not possible to ensure knowledge no matter how many times a certain event is repeated. For example, through induction, the human being knows that the sun will rise the next day for the simple fact that it has always happened that way. However, this is not a true guarantee that the same thing will actually happen.

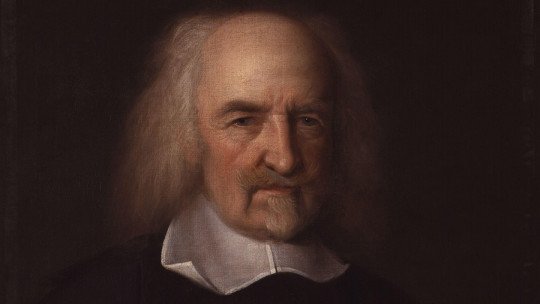

5. Thomas Kuhn

This philosopher considered that what Popper proposed was not sufficient reason to delimit a certain theory or knowledge as non-scientific. Kuhn believed that a good scientific theory was something very broad, precise, simple and coherent. In applying himself, the scientist must go beyond rationality alone, and be prepared to find exceptions to your theory Scientific knowledge, according to this author, is found in theory and rule.

In turn, Kuhn came to question the concept of scientific progress, since he believed that with the historical development of science, some scientific paradigms were replacing others, without this in itself implying an improvement with respect to the previous ones: passing from one system of ideas to another , without these being comparable. However, the emphasis he placed on this relativistic idea varied throughout his career as a philosopher, and in his later years he displayed a less radical intellectual stance.

6. Imre Lakatos and the criterion based on scientific development

Lakatos developed the scientific research programs. These programs were sets of theories related to each other in such a way that some are derived from others

There are two parts in these programs. On the one hand there is the hard core, which is what the related theories share On the other hand are the hypotheses, which constitute a protective belt for the core. These hypotheses can be modified and are what explain the exceptions and changes in a scientific theory.