Everything is number. That is the maximum of the Pythagoreans, the community of Ancient Greece that contemplated the universe as an ordered whole in which divinity was expressed In this way, the cosmos (Greek word meaning universe) was manifested through numbers and musical proportion, erected as the true sources for human purification.

In other words (and contrary to what you may think), the Pythagoreans were not simply mathematicians or philosophers. The teachings of Pythagoras, the great teacher, were located in a mystical-scientific framework that sought to provide a profound explanation of existence, beyond the purely rational or empirical. In fact, the Pythagoreans constituted what today we would call sect (they had their own oaths and their own initiation rites), greatly influenced, as we can see, by the mystery cults so in vogue in Greece at the time.

Who were the Pythagoreans, then, and what did their philosophy consist of? In today’s article we unravel the “secrets” of this community that was so influential in Greek culture of the 6th and 5th centuries BC.

The Pythagoreans: sect or community?

There is a lot of literature about the Pythagoreans. His strange teaching, a curious mix of science and mysticism, has inspired legends, novels and films. However, who were they really?

Pythagoras of Samos, the teacher

We must start from the beginning, which is none other than the birth in Samos (Asia Minor), around the year 570 BC, of a character who was going to change the philosophical perspective of Greece. We are talking, of course, about Pythagoras of Samos (570-490 BC), the founder of what would later become the Pythagorean school of Croton.

Probably born into a family of merchants (we know the name of his father, a certain Menesarchus), Pythagoras had the opportunity to make a series of trips to the East that were fundamental for the creation of his philosophy. From Egypt he acquired geometric knowledge; In Babylon and Chaldea he drank from their very ancient astrology. It is even probable that he encountered Zoroaster (c. 628-551 BC), or at least his doctrine, during his travels through Persia. From Zoroastrianism, a religion that spread rapidly throughout the East in the last centuries before Christ, the young Pythagoras probably retained the idea of fire as a purifying element

Mysterious rites

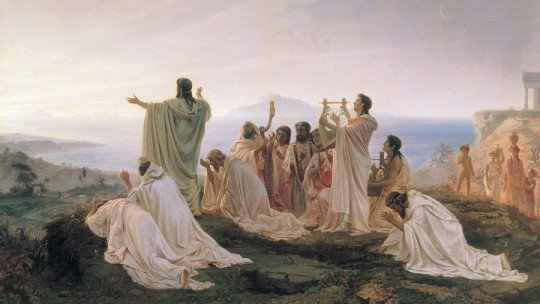

Upon his return to Greece, Pythagoras settled in Croton, in Magna Graecia (southern Italy), where he founded a school that would soon gain several followers. This first Pythagorean generation already laid down the foundations of what would be the general doctrine of fraternity: an indisputable union between rationality and mystical contemplation. In reality, after the Persian invasions, the Hellenic territories were already quite ripe for the acceptance of religions from Asia. The Eleusinian rites flourished, as well as the Dionysian and Orphic rites. All of them They had in common both the hermeticism of their teachings and the various purification rites to which the initiates had to submit.

The nature of the Pythagoreans must be framed in this mysterious current that bathed Greece around the 6th century BC. Therefore, we can affirm, using current slang, that they were what we would call a sect today. We know that the Pythagoreans had an oath, the “Pythagorean oath”, in which they mentioned Pythagoras without calling him by his name (they called him that one) and made reference to the “holy Tetraktys” that he had given them. That is, the philosopher was practically considered a prophet, a teacher, an initiator.

A numerical and musical universe

What was this “holy Tetraktys” that Pythagoras had given to his disciples? Graphically, it was represented as ten points distributed in four lines, which drew a triangle and represented the four manifestations of the universe that, together, were everything.

First there was the One, the Unity, identified with the Divinity, eternal and indivisible. Then, there was the Dyad, that is, the Two, which represented the split of this primordial point and which symbolized the intrinsic duality of everything (masculine-feminine, night-day…). The Triad, that is, the Three, were the three levels into which the world is divided: heaven at the top and hell at the bottom, with earth in the middle module. Finally, The Quaternary or number Four symbolized the four elements: earth, air, fire and water The four lines (1+2+3+4) add up to ten, that is, the Decade, which represented the entire universe.

We can see how, indeed, for the Pythagoreans number was the essence of everything, the main manifestation of God. Consequently, music, structured in regular and proportional intervals, was equally related to the cosmos; In fact, the Pythagoreans considered that cosmic movement produced music, but that it was so constant and perfect that the human ear was unable to perceive it.

The eternal movement of the soul and the path of purification

Movement was essential in Pythagorean doctrine. Everything divine moved eternally; Therefore, the soul, as immortal, must also move. From here the Pythagoreans deduced its “eternal return” an idea greatly influenced by Persian mysticism, which stated that the soul was constantly reincarnated and that only its definitive liberation would remove it from the infinite circle of movement.

How, then, to achieve this liberation of the soul? The Pythagoreans not only formed a theory, but also constituted a way of life. They advocated an absolutely pure life, in which contemplation of the universe and constant purification were basic pillars. The Pythagorean community had quite strict rules of conduct, among which was not consuming meat, but also other quite absurd ones such as not stoking the fire with iron or not picking up anything that had fallen.

In principle, these rules of behavior were based on the harmony of the cosmos, from which the human being could not separate himself if he truly desired purification. The “harmony of the spheres”, of divine creation, was the mirror in which the Pythagorean had to observe himself, in order to recreate in his life and in his environment the same harmonious movement of the universe. Only in this way was the elevation of the soul possible.

Fire as a divine engine

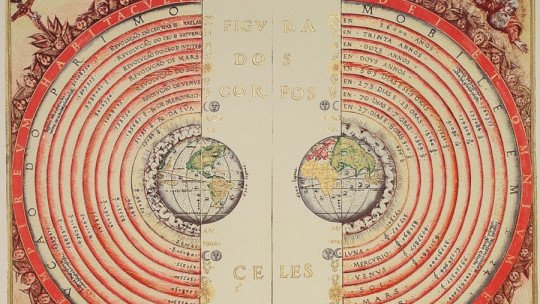

Probably derived from the teachings of Persian Zoroastrianism, Pythagorean philosophy also placed fire as the indispensable center of universal movement. In this way, it originates an early non-geocentric theory that placed divine fire as the center of the cosmos and as the prime mover of the rest of the harmonic movement, around which the stars and planets revolved; among them, the earth.

This idea will be collected through the centuries and will reach the European Middle Ages, especially through the philosophy of Aristotle. Saint Thomas Aquinas, for example, will speak of a “first unmoved mover” (that is, God) as the driving force of everything.

Split and formation of the Pythagorean generations

The community founded by Pythagoras in Croton split at the end of the 6th century BC due to political and social problems with the city. But that does not mean Pythagoreanism ends. The master’s disciples emigrate and settle in other Greek cities, where they continue his teachings and their particular way of life.

At that time, The Pythagorean fraternity had already divided into two very different groups : the matematikoi (the “knowers”) and the acousmatics (“hearers”). The main difference was that the former had the power to speak and show their opinion on the Pythagorean doctrine, while the hearers could only listen and, of course, remain silent. Traditionally, these listeners have been identified as the novices or initiates, while the matematikoi would represent the experience within the community. All this demonstrates, once again, the initiatory character of the Pythagorean fraternity.

The master Pythagoras died in Metaponto on an unknown date, although it is believed that it was at the beginning of the 5th century BC Pythagoreanism continued its path in the current called Neopythagoreanism, which survived long after the death of its initiator.

The Dutch mathematician Bartel Leendert Van der Waerden (1903-1996) distinguished five generations within Pythagoreanism , and highlighted some main thinkers from each of them. The first is the one established by Pythagoras, and begins approximately in the year 530 BC. In the second generation, Hypasus of Metaponto stands out, supposedly murdered for revealing secrets reserved for the members of the community.

The third generation is the so-called “anonymous generation”, by the way, highly praised by Aristotle. In the fourth, already in the 5th century BC, Philolaus and Theodore stand out, and in the fifth and last, corresponding to the first half of the 4th century BC, Archytas of Taranto (428 -345 BC).